A blueprint for Canada: The 1864 Quebec Conference

The Canada we know today took shape during the autumn of 1864.

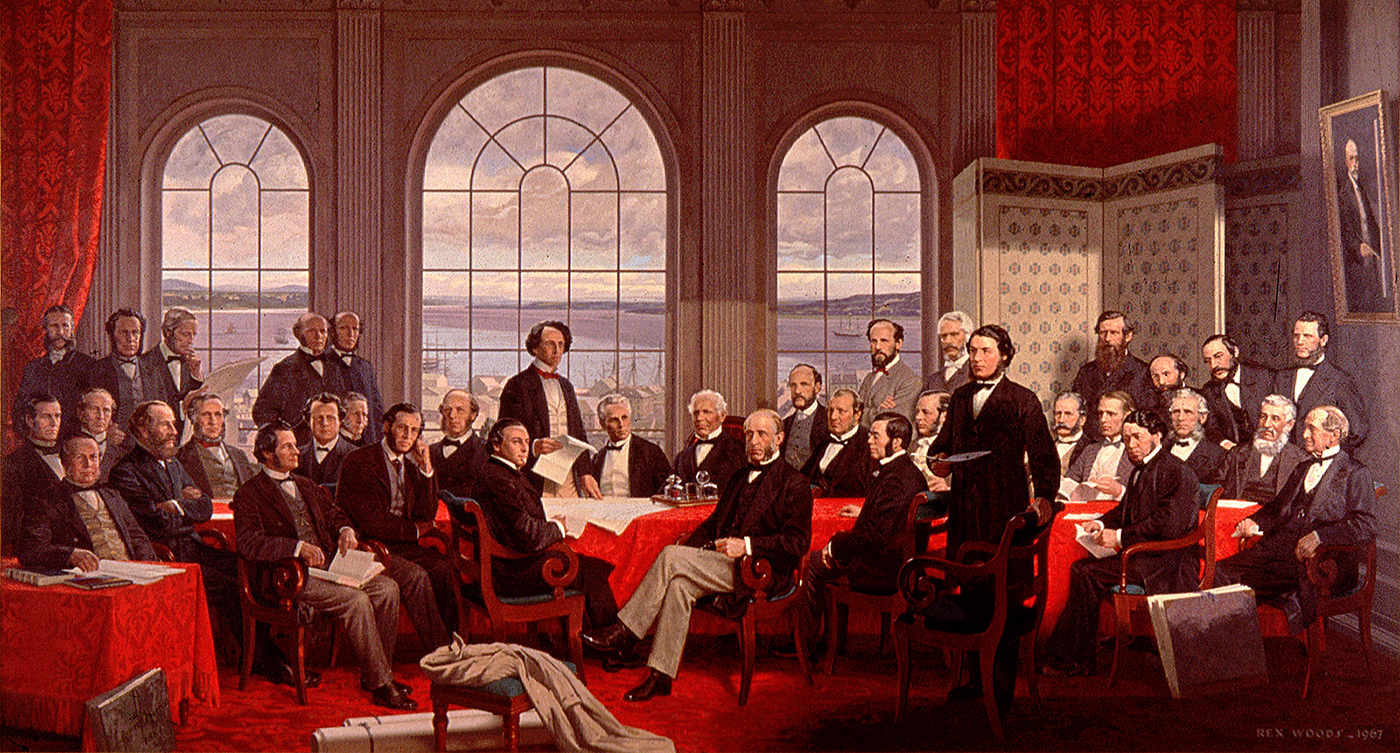

It started in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, in early September when delegates representing the Province of Canada (today’s Ontario and Quebec) joined representatives of Britain’s Maritime colonies P.E.I., Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to discuss political union.

They were treated to dinners, balls and picnics, good weather, good company and good will. Following a week of negotiations, they toasted their success; the dream of uniting Britain’s North American colonies was now an agreement in principle.

Delegates reconvened a month later in Québec, under grey skies and unrelenting rain, to tackle the hard, slogging work of spelling out how the country would be governed.

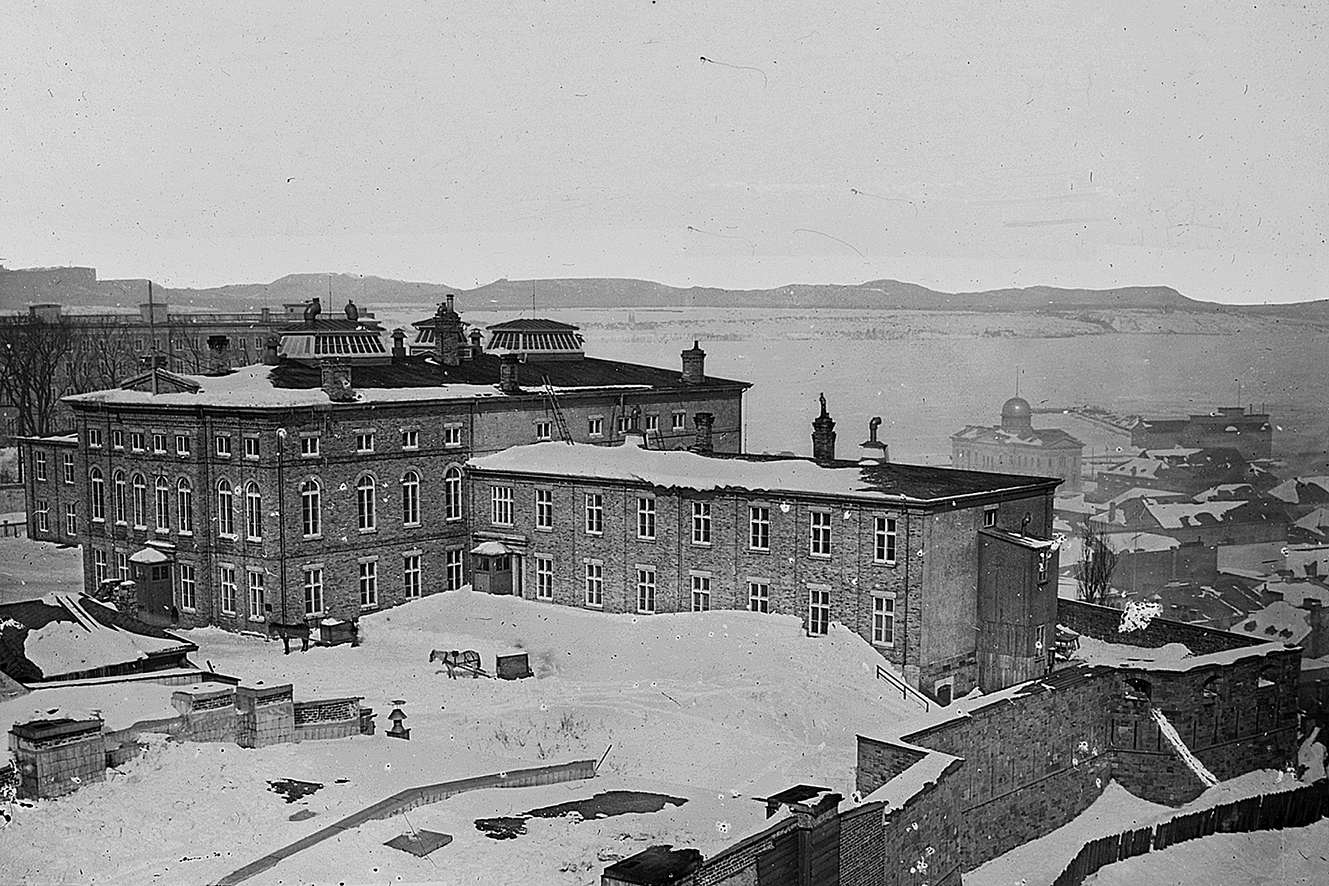

Meeting in the reading room of Québec’s newly built Parliament Building, delegates negotiated for six hours or more a day, with day-to-day legislative work occupying several more.

Reporters were denied access to the meetings and delegates kept only sporadic notes.

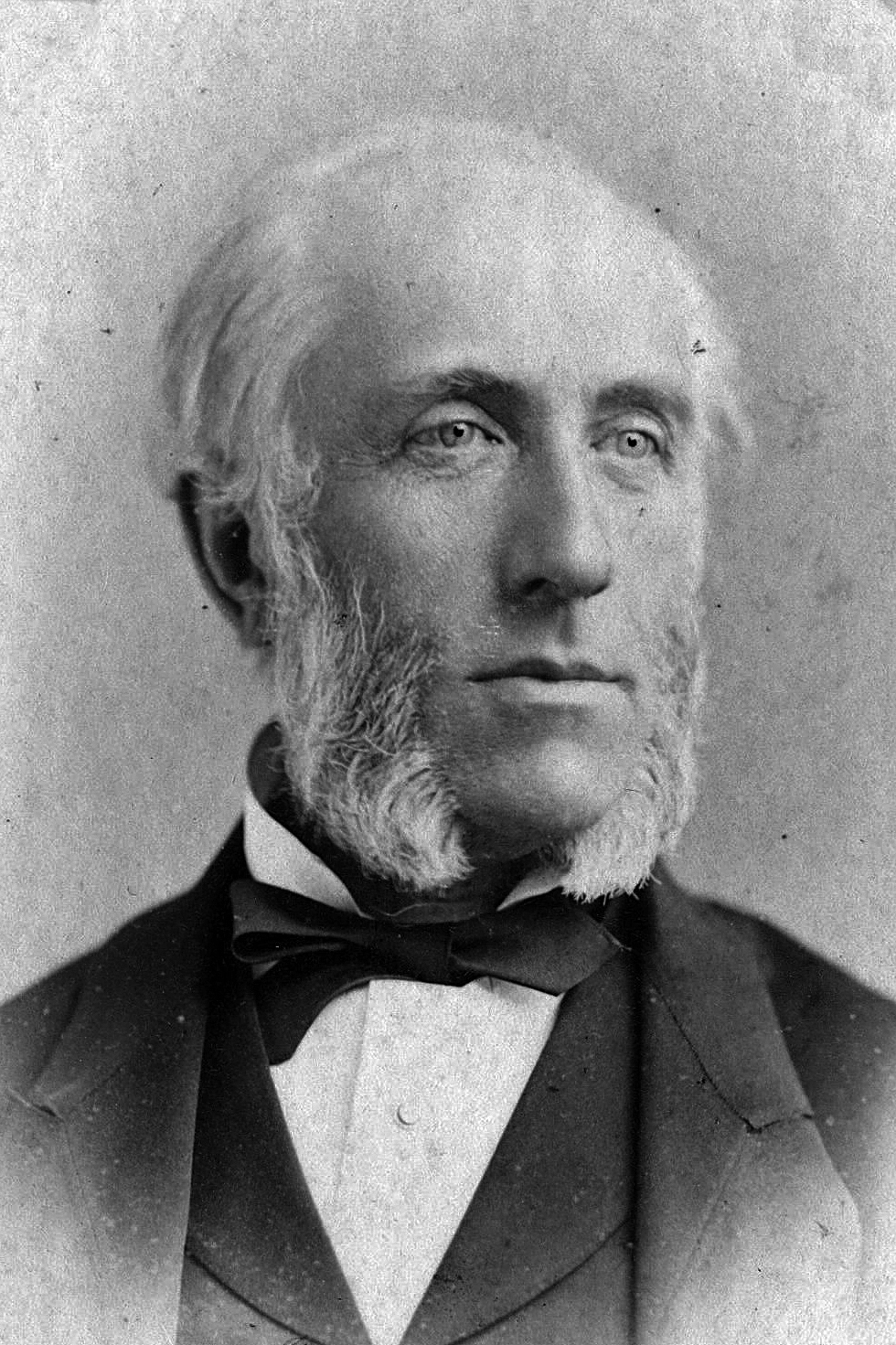

Enter Mercy Coles, the 26-year-old daughter of P.E.I. delegate George Coles. She accompanied her father to the Charlottetown and Quebec Conferences and kept a diary of her experiences.

Historian Anne McDonald paints a vivid portrait of the young writer in her book Miss Confederation: The Diary of Mercy Anne Coles.

“Because there were hardly any minutes kept, Mercy’s diary is one of the few windows we have into the atmosphere of the conference and what the Fathers of Confederation were thinking.” Ms. McDonald said. “It’s a very lively account.”

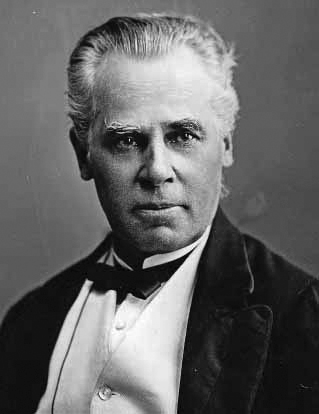

Québec was a magnificent site for the conference. Its colourful military garrison, its British-born governor general, Viscount Charles Monck, and the court he maintained at his official residence, Spencer Wood, reenacted the pomp of British aristocratic society on Canadian soil.

“Where Charlottetown was spontaneous and impromptu, everything was grander and more formal in Quebec,” Ms. McDonald said. “The balls and banquets made a statement that this conference was a big deal, that Confederation was a big deal and that the sheer size of the country they were proposing was a big deal.”

During 16 days of negotiations, the minutiae of government was hammered out. The result was the Quebec Resolutions, 72 provisions that formed the basis of the British North America Act, Canada’s founding constitution.

First on the agenda: should Canada be a federal union, like the United States, with power shared between a central government and its constituent provinces? Or should it be a legislative union, like Great Britain, with powers concentrated in a single national legislature?

Many of the delegates were leery of federal union, convinced it had inflamed the Civil War raging to the south. Fundamentally, though, legislative union was a non-starter. The Maritime colonies and French Canada insisted on retaining some form of local government that would give them autonomy over regional matters, minority rights and cultural issues.

The next question: how should those powers be distributed?

The provinces would retain control over local issues, including education, language and municipalities. The federal government would have authority over the postal service, the military, foreign affairs, money, foreign trade and criminal law.

Following the British model, Parliament would have two houses. The upper, which became known as the Senate, would reflect the principle of regional representation, the lower — the House of Commons — the principle of representation by population.

Seats in the elected house would be apportioned according to population. Ontario was allocated 82 seats, Quebec 65, Nova Scotia 19 and New Brunswick 15. As the country’s population grew, seats would be redistributed every 10 years based on the latest census data.

The delegates resolved that the upper house would be appointed, with each region — Ontario, Quebec, and the three Maritime provinces — allocated 24 seats regardless of population. In this way, the Senate would be the defender of regional and minority interests, a bulwark against the overwhelming dominance of the English majority in the west.

A view of Québec in the late 1800s, looking towards Dufferin Terrace, before construction had begun on the iconic Château Frontenac. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

A view of Québec in the late 1800s, looking towards Dufferin Terrace, before construction had begun on the iconic Château Frontenac. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

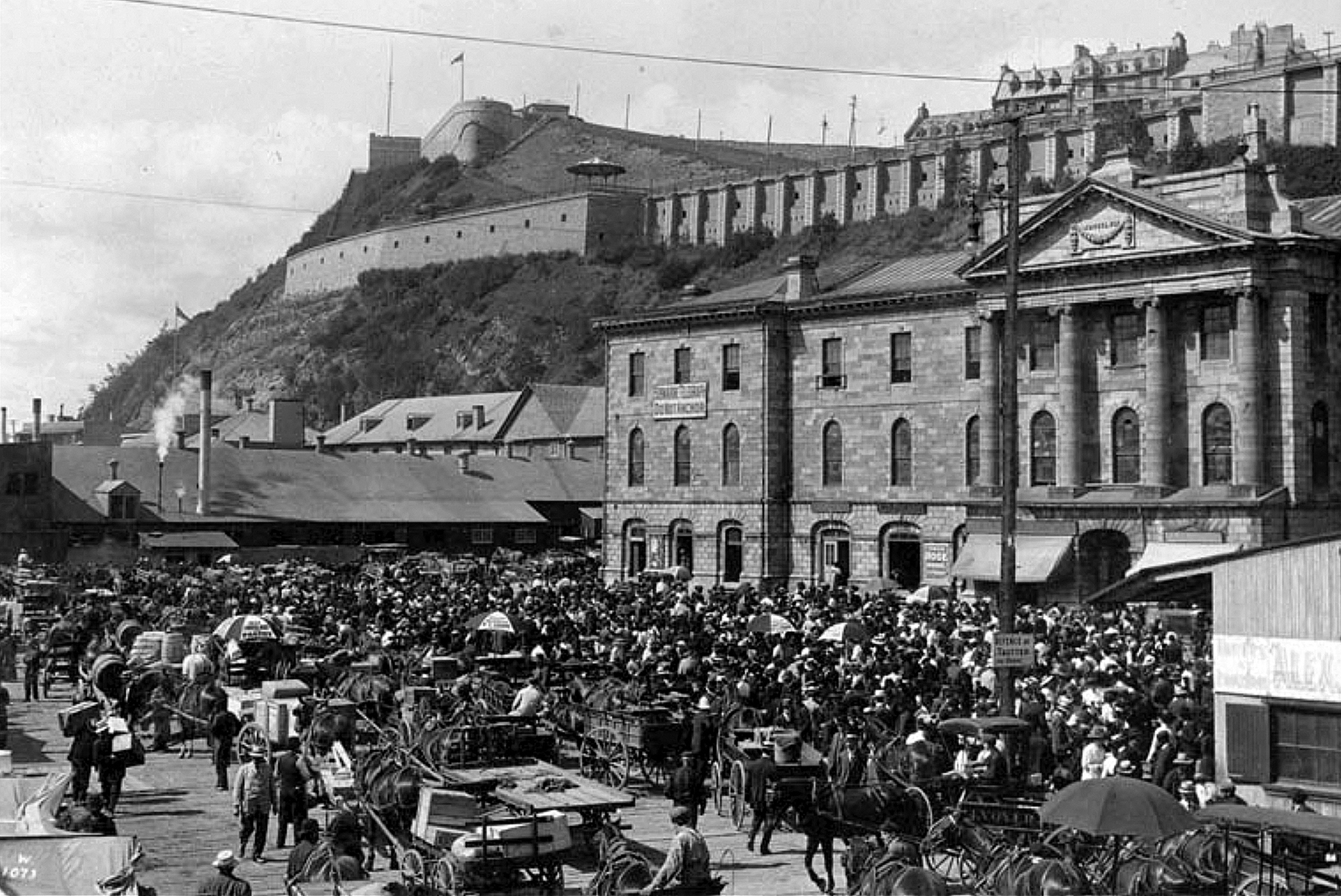

Québec’s Champlain Market in the late 1800s, looking towards Dufferin Terrace and the Citadel. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Quebec Conference sessions were held in the reading room of Québec’s Parliament Building, where the Province of Canada’s Parliament met from 1860 to 1865. The building burned down in 1883. Montmorency Park occupies the site today. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Quebec Conference sessions were held in the reading room of Québec’s Parliament Building, where the Province of Canada’s Parliament met from 1860 to 1865. The building burned down in 1883. Montmorency Park occupies the site today. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Spencer Wood was Governor General Viscount Monck’s official residence near Québec. He hosted dinners for delegates and their families throughout the conference as well as a formal ball to launch the event. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Spencer Wood was Governor General Viscount Monck’s official residence near Québec. He hosted dinners for delegates and their families throughout the conference as well as a formal ball to launch the event. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Finally, to the relief of the Maritimers, delegates resolved that the federal government would fund completion of the Intercolonial Railway from Québec to Halifax.

The delegates had reached an agreement, but that agreement still had to be ratified by each colony’s legislature.

During those debates, regional opposition to Confederation grew, toppling governments and nearly scuttling Nova Scotia and New Brunswick’s entry into Confederation.

P.E.I. opted out, disenchanted with the terms it received.

By 1873, financial troubles caught up with it, and a generous offer from the Canadians convinced P.E.I. to join.

The Fathers of Confederation had drawn up a blueprint for how Canada would be governed.

They had provided a draft constitution, and in doing so, had invented an entirely new model of government, combining parliamentary central authority with significant powers devolved to the provinces.

The next major milestone would be the 1866 London Conference, where the Canadians’ proposal was prepared for Queen Victoria’s approval.

The resulting constitution — the British North America Act — received Royal Assent on March 29, 1867, and went into effect on July 1, 1867, the birth of the Dominion of Canada.

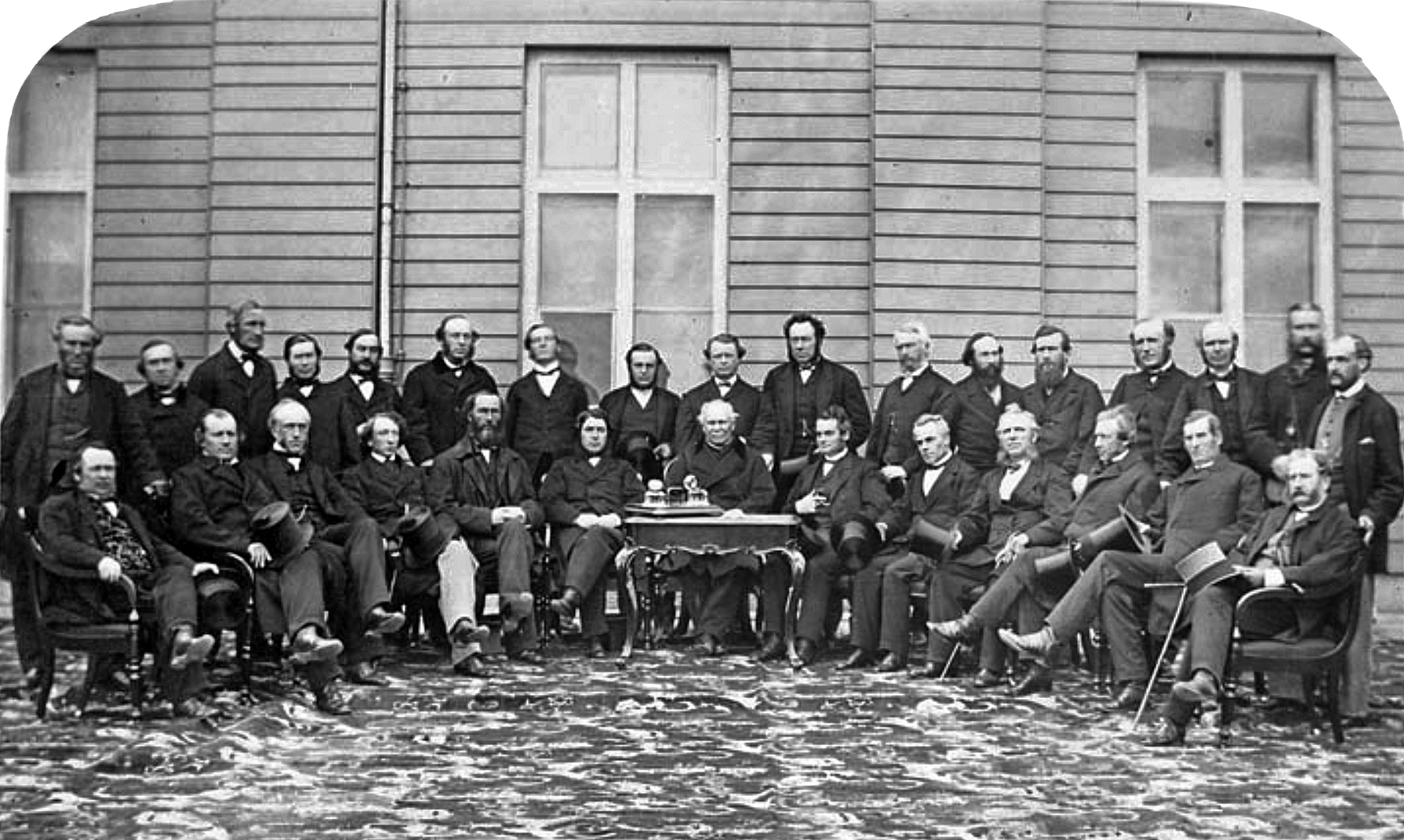

Delegates to the Quebec Conference gather for a photo at Spencer Wood, the governor general’s official residence. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)