'A diary of Canada in stone': Parliament’s carving program and the Dominion Sculptors who shaped it

In February 2019, the Senate moved to the Senate of Canada Building, a former train station built in 1912. The Senate will occupy this temporary location while Parliament’s Centre Block — the Senate’s permanent home — is rehabilitated.

Although Centre Block is shuttered for rehabilitation work, Canadians can still experience its art and architecture through the Senate’s immersive virtual tour.

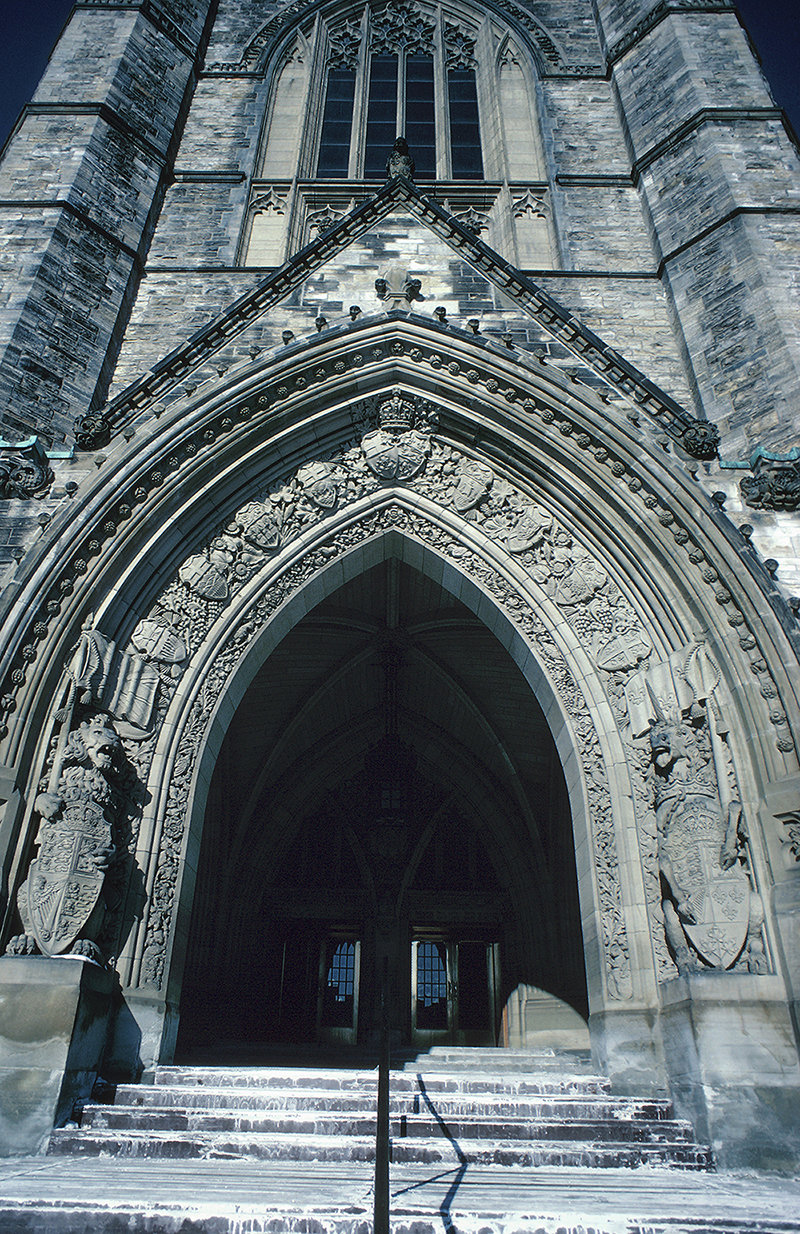

The United Kingdom, Barbados, Hungary — like Canada, these countries have parliament buildings that are striking examples of Gothic Revival design.

But Centre Block, which anchors a majestic trio of buildings on Ottawa’s Parliament Hill, is unique for one reason: it remains a work in progress.

When the original Centre Block burned to the ground in February 1916, chief architect John A. Pearson envisioned its replacement as a continuing showcase for sculpture. As the new Centre Block took shape, Mr. Pearson left thousands of stone blocks uncarved for future sculptors to complete.

“He imagined it as a pictorial diary of Canada in stone,” said Dominion Sculptor Phil White, Parliament’s official carver and custodian of its sculptural heritage.

“No other country has a program like that.”

Mr. Pearson’s artistic foresight has allowed generations of Parliament Hill carvers to leave their mark on Centre Block, making the building as memorable as it is magnificent.

For the last 85 years, that work has been administered by the Dominion Sculptor, consulting closely with the offices of the Speaker of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Commons. Read on to learn about the five chief carvers who have overseen Parliament’s sculpture program to date:

Cléophas Soucy (1936-1950)

Cléophas Soucy was born in Montréal to a family of carvers and moved to Ottawa in 1919 to work on the reconstruction of Centre Block.

Consistent and reliable, he stepped in when crisis erupted. When chief carver Ira Lake abruptly resigned in 1927 — just as work on the Peace Tower was reaching full swing — Mr. Soucy calmly steered the project to completion.

Centre Block carving ground to a halt during the Great Depression but, when the program sputtered back to life in 1936, Mr. Soucy was made a permanent employee of the Department of Public Works with the auspicious title Dominion Sculptor.

Mr. Soucy’s team of thirteen sculptors completed the exterior carving on Centre Block as well as the bulk of the carvings in the Senate and House of Commons. When he died suddenly in 1950, he left a cache of unrealized designs but, crucially, he left the program on a stable footing.

William Oosterhoff (1950-1962)

Dutch-born William Oosterhoff studied at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Amsterdam before making his way to Canada’s capital. He had only been with the parliamentary sculpting program for a year when he was appointed Mr. Soucy’s successor.

By the 1950s, the golden age of stone carving was fading and few trained sculptors were coming up through the ranks. As a result, Mr. Oosterhoff personally trained his entire four-person team.

The quintet completed a series of elaborate carvings in Confederation Hall, Centre Block’s octagonal rotunda, that celebrates the provinces through their native plants and animals. In the late 1950s, the team turned its attention to the Senate foyer, completing a soaring 30-metre-long frieze that depicts early figures in Canada’s history, including explorers John Cabot and Jacques Cartier.

In 1962, Mr. Oosterhoff retired and moved to Hamilton, Ontario.

Eleanor Milne (1962-1993)

Eleanor Milne trained under Group of Seven founder Arthur Lismer at the Art Association of Montreal, now the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and at Syracuse University under the Croatian avant-garde sculptor Ivan Mestrovic. Prolific, versatile and with an academic background in art history and conservation, she beat out 21 candidates in a national competition to find Mr. Oosterhoff’s replacement.

During her 30-year tenure, Ms. Milne and her team of four carved large sections of the House of Commons Chamber and its adjoining foyer. She also worked in the Senate foyer, carving and restoring corbel portraits of King George VI, Queen Victoria and King Edward VII.

Ms. Milne revolutionized the way carvers worked. For decades, the team had sculpted on site, working late nights after the Senate and House adjourned. In 1973, carving moved to an east-end Ottawa workshop and completed carvings were shipped back to Centre Block for installation.

Carving also became less laborious under Ms. Milne’s direction. Her predecessors had first created full-scale plaster models that were then copied in stone, detail for detail. Ms. Milne, instead, had her assistants transfer her preparatory drawings onto the stone, giving her colleagues licence to develop the design as they saw fit.

Ms. Milne received the Order of Canada in 1988 and retired in 1993.

Maurice Joanisse (1993-2006)

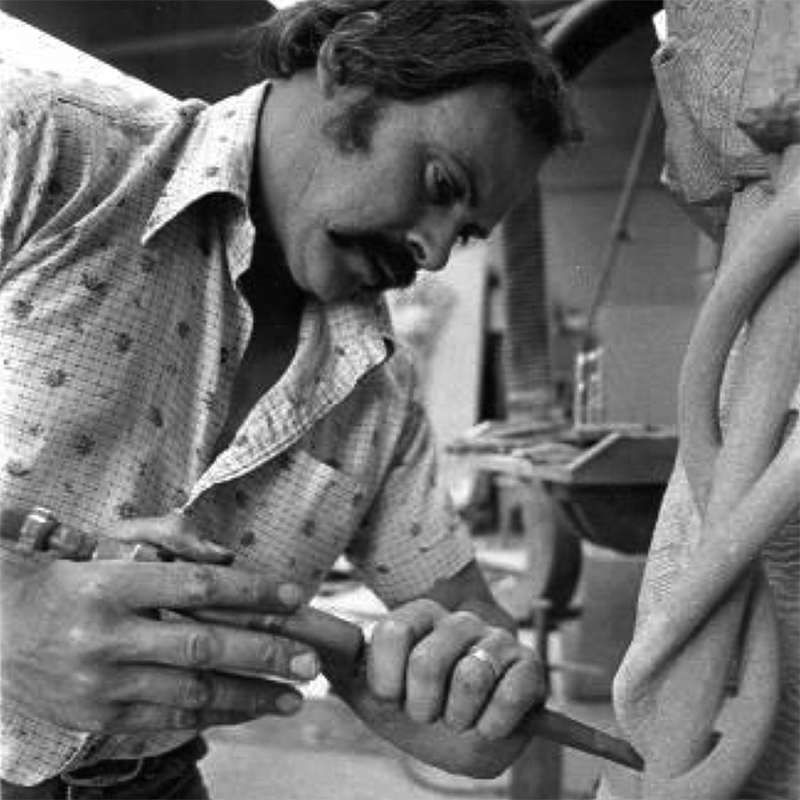

Maurice Joanisse stepped into the Dominion Sculptor role upon Ms. Milne’s departure. First hired in 1971, he learned his craft as an apprentice rather than through formal academic training.

“There’s no school in Canada where you can learn to do this. This is a tradition and style you learn on the job the old-fashioned way,” Mr. Joanisse said in a 2001 interview with Legion Magazine.

He quickly went to work on the History of Canada frieze in the House of Commons foyer and completed several ambitious projects already underway, including the House of Commons’ Evolution of Life series.

Mr. Joanisse also undertook a two-year tally of the exterior ornamentation on the three Parliament buildings — Centre Block, East Block and West Block — that documented more than 3,000 sculptures. He rode a crane-mounted workman basket to the rooftops, recording every detail and every imperfection.

“In many cases I had to take immediate action to secure pieces so they didn’t fall and injure someone,” he told Legion Magazine in 2001.

Mr. Joanisse announced his retirement in 2005. Since he worked alone throughout his 13-year tenure, there was no successor groomed for the role. Once again, Parliament held a contest to find its next Dominion Sculptor.

Phil White (2006-2021)

Phil White beat out 75 applicants for the title. Introduced to carving by his grandfather, a master mason and woodcarver, Mr. White came to Ottawa in 1987 as a conservator and sculptor for the Canadian War Museum.

After Mr. White accepted the offer to helm the parliamentary sculpture program, Mr. Joanisse agreed to stick around and mentor his successor during the transition.

Mr. White completed a flurry of commissions coinciding with Queen Elizabeth II’s Diamond Jubilee in 2012, including a corbel portrait of the Queen in the Senate foyer and a portrait bust.

Increasingly, he has been called upon to carve off Parliament Hill. He spent much of 2016 and 2017 creating designs for the Senate of Canada Building in Ottawa’s refurbished central train station.

With more than 150 unornamented blocks of stone remaining to be carved inside Centre Block and century-old sculptures in need of repairs, Mr. White recently hired two assistants.

“There’s plenty of work still to do,” Mr. White said. “I see the program continuing long after my term.

“My plan is to leave it on as solid ground as my predecessors.”