Canadian Gothic: Ottawa’s original Parliament Building

In February 2019, the Senate moved to the Senate of Canada Building, a former train station built in 1912. The Senate will occupy this temporary location while Parliament’s Centre Block — the Senate’s permanent home — is rehabilitated.

Although Centre Block is shuttered for rehabilitation work, Canadians can still experience its art and architecture through the Senate’s immersive virtual tour.

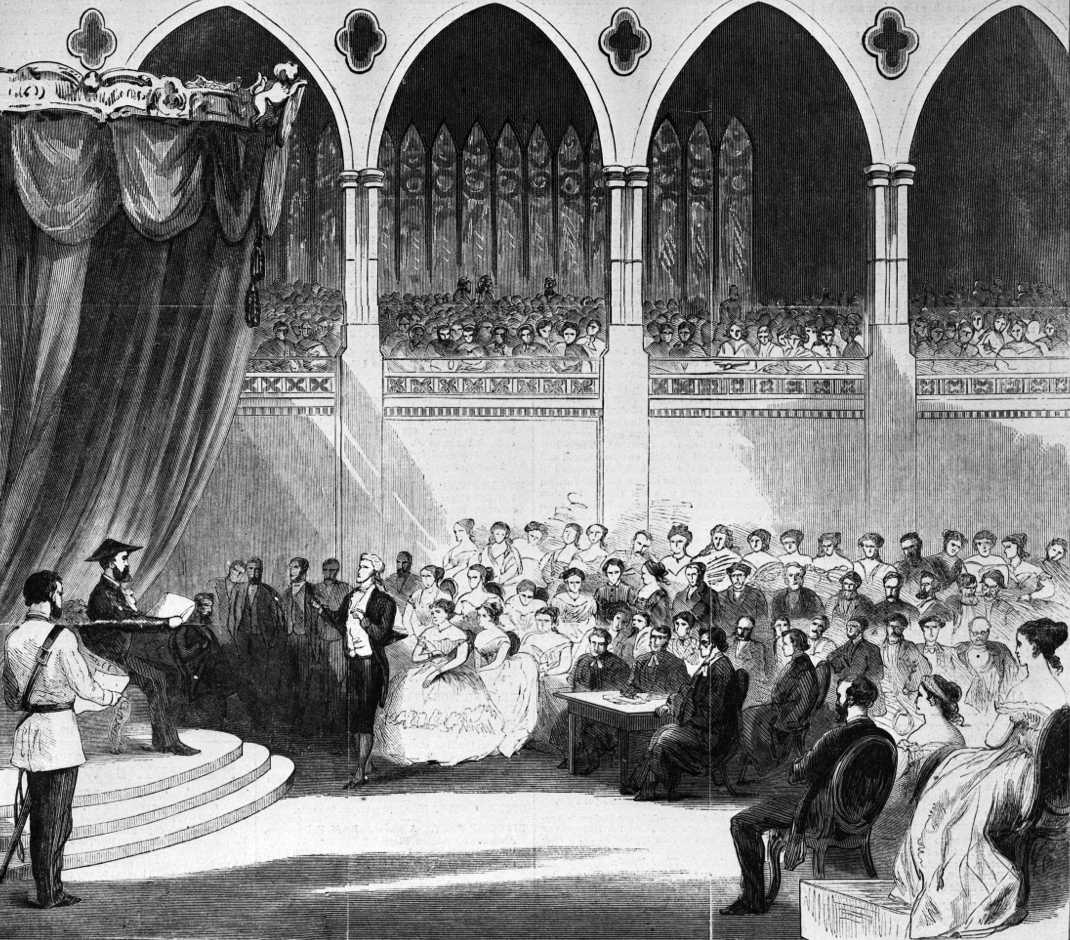

Centre Block, with its iconic Peace Tower, is an instantly recognizable symbol of Canada — a fixture on banknotes, stamps and postcards that embodies everything Canada has stood for since the First World War. The original 1866 building, which housed Parliament for 50 years before it burned to the ground in 1916, reflected a very different Canada — one firmly ensconced in the British orbit.

It wasn’t simply British in influence; it was a British building through and through. When Queen Victoria chose Ottawa to be Canada’s permanent capital in 1859, there was no talk of Confederation. This was still a colony of the United Kingdom, albeit a restless one the capital of which had moved seven times in 26 years.

An architectural competition

The Department of Public Works put out a call for submissions in May 1859, allowing architects a scant 12 weeks to submit proposals for a new parliamentary complex.

Rushing to meet the deadline, 21 architectural firms responded with 32 design proposals, supported by 298 drawings.

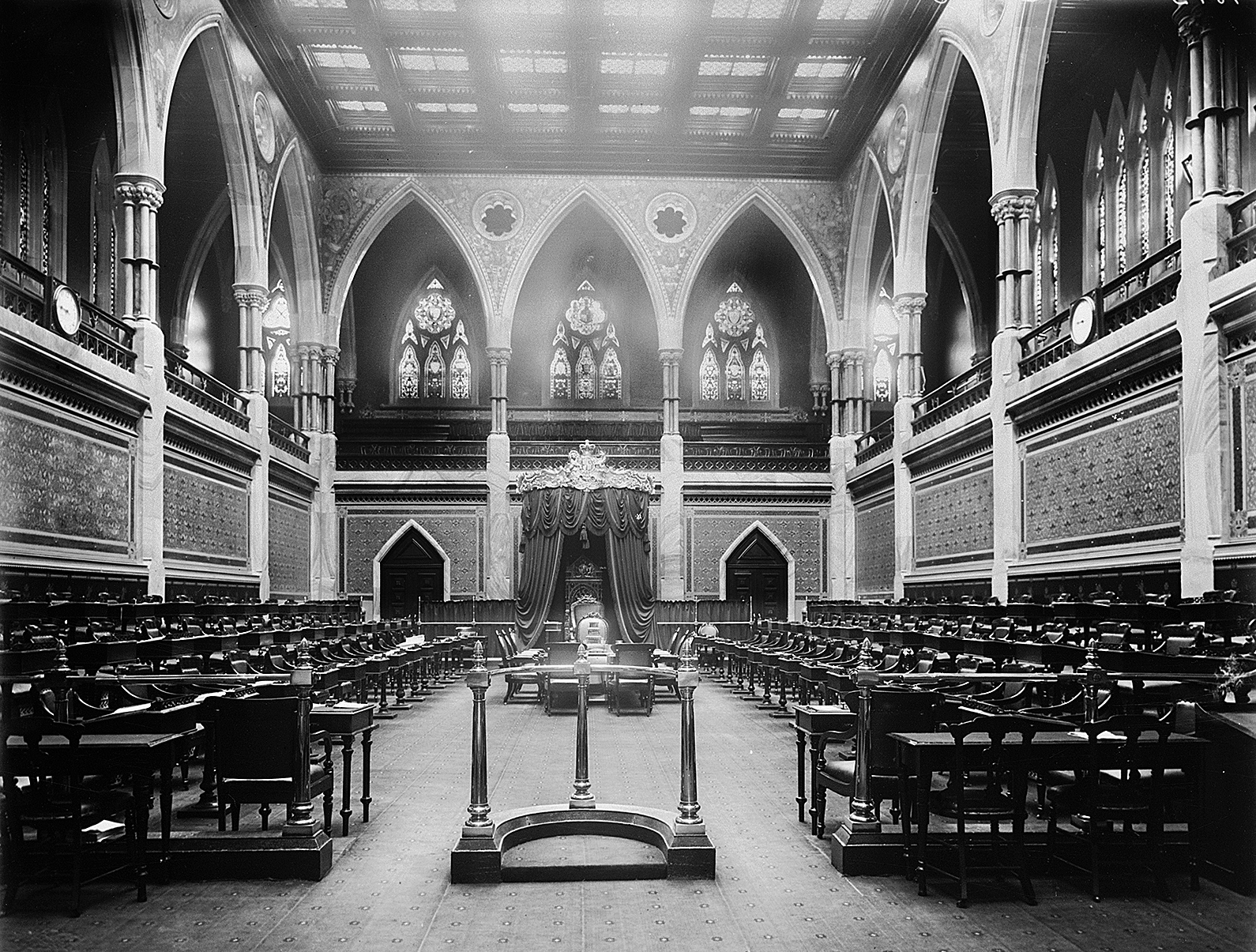

The finalists fell into two distinct camps. Domed neoclassical buildings that evoked the temples and basilicas of ancient Rome vied with Gothic Revival structures that echoed the cathedrals and guild halls of medieval Britain.

Englishman Thomas Fuller and Canadian Chilion Jones had closely followed the architectural revolution happening in Britain and predicted the mania for medieval revivalism would soon sweep Canada. They won the contract with their proposal for an imposing Gothic Revival complex of towers, courtyards, mansard roofs and pointed arches.

“Canada was a part of Britain when it was proposing its Parliament buildings, so it adopted Gothic Revival, a distinctly British style,” House of Commons curator Johanna Mizgala said. “Canada clearly wanted to echo the architecture of the British Houses of Parliament, which were just being completed.”

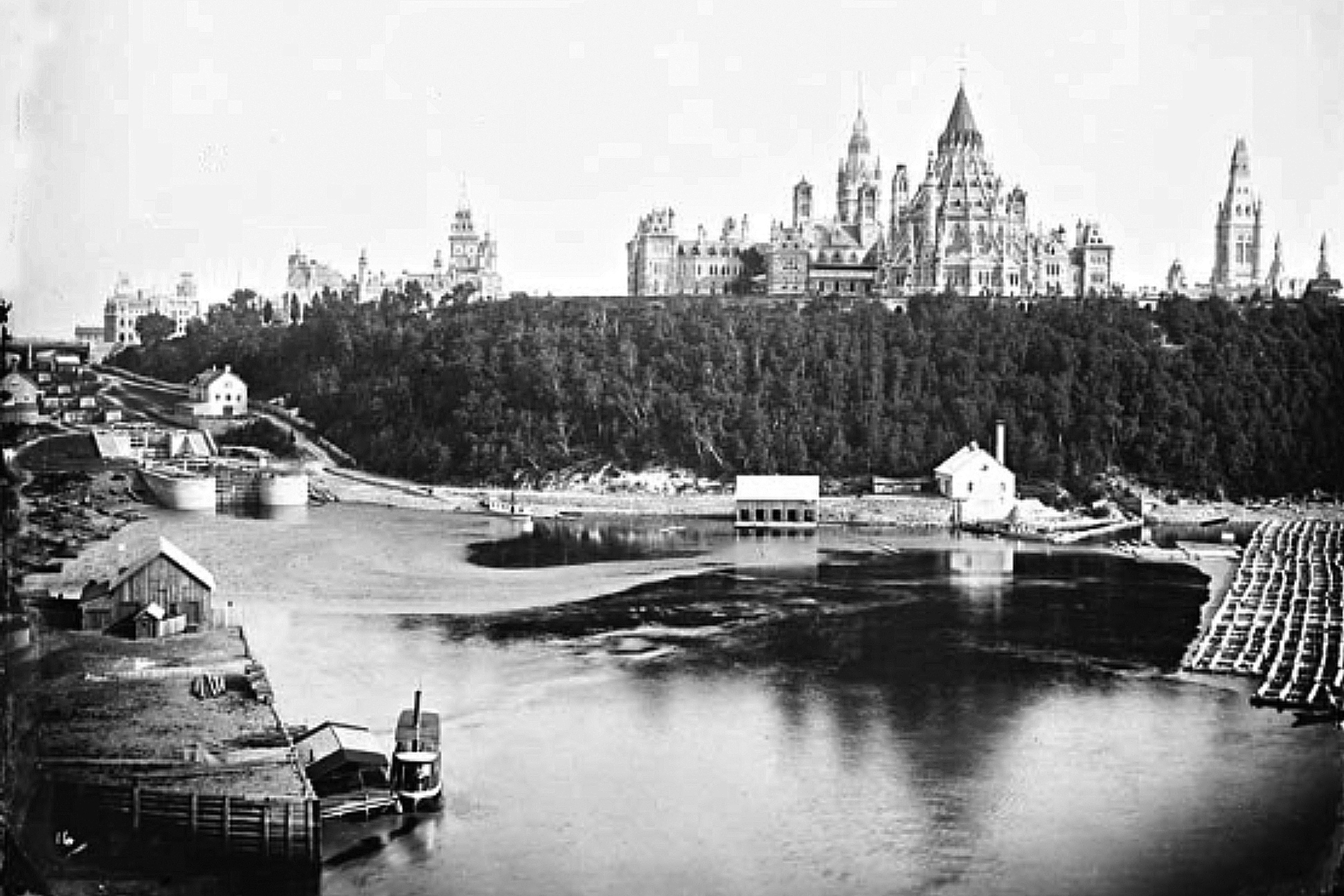

Fuller and Jones’ picturesque design was well suited to the site — a nine-hectare lawn at the heart of the new capital, perched at the edge of a wooded cliff overlooking the wild, surging Ottawa River.

“The Gothic style was about celebrating nature,” said Dominion Sculptor John-Philippe Smith, Parliament’s official sculptor and custodian of its huge collection of stone and wood carvings. “It was a very Victorian concept — architects saw virtue in nature and wanted to reflect those ideals in their civic buildings.”

Construction on a massive scale

The scale of the project dwarfed anything ever attempted in North America. The four-storey Parliament Building was 144 metres wide and 120 metres deep. Its centrepiece, the Victoria Tower, topped out at 76 metres when its spire and iron crown — a nod to Queen Victoria’s role in selecting the capital — was completed in 1878.

The walls were faced with Nepean sandstone, quarried just west of Ottawa. Red sandstone from Potsdam, New York, and buff-coloured Berea sandstone from Ohio formed window accents and decorative details. The artisans who worked that stone were almost exclusively English, Scottish and Irish emigrants, trained in a 600-year-old tradition of Gothic ornamentation.

“In terms of design elements, you wouldn’t have seen the huge array of Canadian animals like squirrels, owls and blue jays you see today on Centre Block,” Mr. Smith said. “The sculptors stuck with traditional characters you’d find, for instance, on a 13th-century cathedral — dragons, lions, grotesques and green men.”

The result was a Victorian building in medieval garb — venerable, stately and very British.

Fire hazard

Like many buildings of the time — interiors full of wooden panelling over plaster and brick — the Parliament Building was vulnerable to fire.

The blaze that destroyed it one bitterly cold February night in 1916 dealt the country a gut-wrenching blow when it was already mired in a bloody, grinding war. Amazingly, the disaster spurred the country to regroup and rethink the original building design. The result — Centre Block, with its mix of European and North American imagery — was bigger, better and distinctly Canadian.