Collegiality, Compromise and Confederation: The 1864 Charlottetown Conference

In the late 1800s, when other nations were taking shape at the end of a bayonet, Britain’s North American colonies were agreeing to terms of union over champagne and lobster — a very Canadian declaration of independence.

The hastily convened Charlottetown Conference of September 1864 brought together delegates representing the Province of Canada (today’s Ontario and Quebec), New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island to discuss political union.

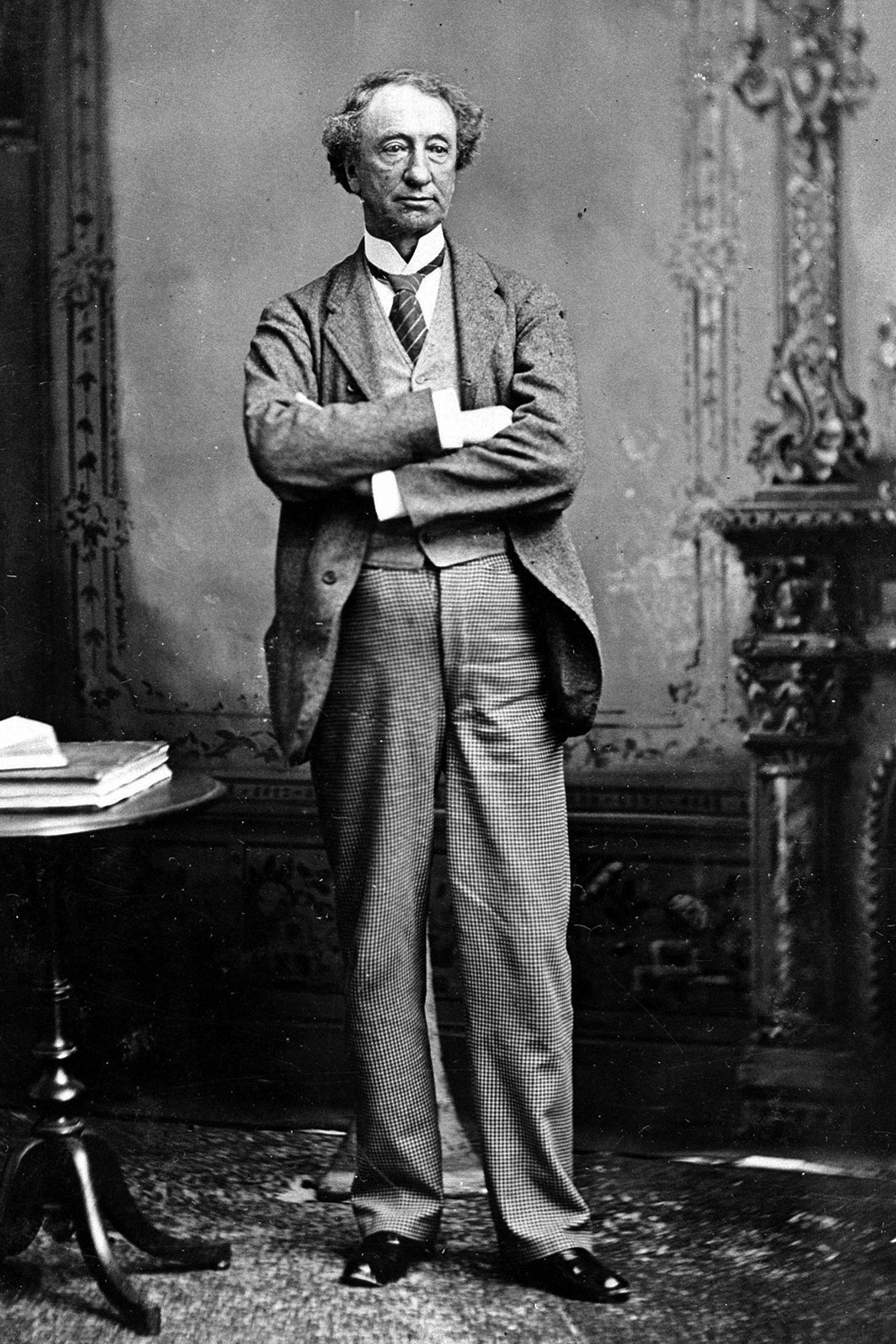

George Brown, leader of the Reform Party in Canada West — today’s Ontario — gushed with optimism:

“We are seeking by calm discussion to settle questions that Austria and Hungary, that Denmark and Germany, that Russia and Poland, could only crush by the iron heel of armed force.”

While the delegates spent hours each day in closed-door negotiations at Province House, Prince Edward Island’s legislative building, after-hours diplomacy continued over champagne and cigars.

Compromise was in the air. The delegates focused on balancing minority and majority rights, the interests of small provinces with those of large ones.

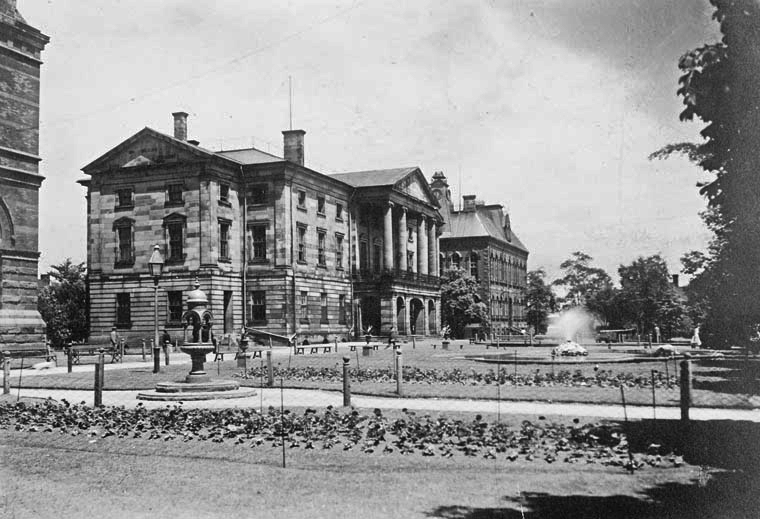

Prince Edward Island’s legislative building, Province House, hosted the 1864 Charlottetown Conference discussions. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Prince Edward Island’s legislative building, Province House, hosted the 1864 Charlottetown Conference discussions. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

“It was necessarily the work of concession,” Brown said, driven by “an earnest desire to do justice to all.”

Delegates tackled the gnawing issues of the day: anglophone-francophone relations, the threat of American annexation, electoral reform and railway building.

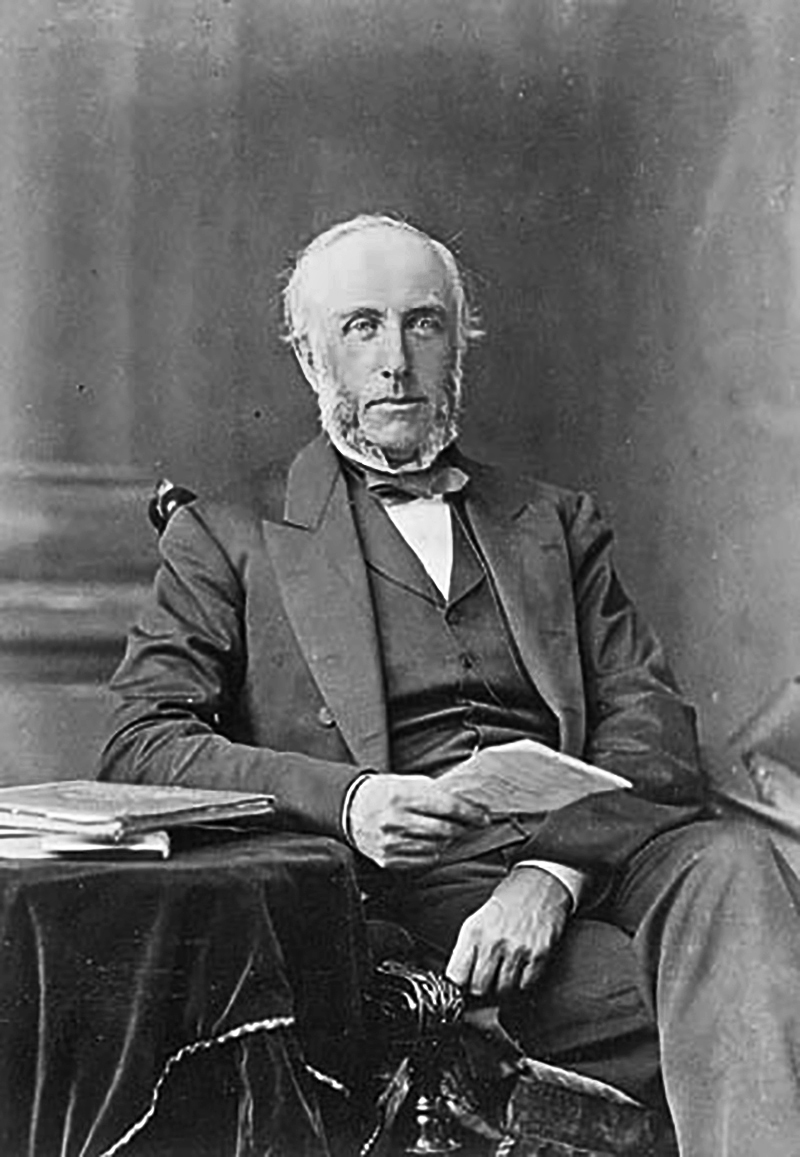

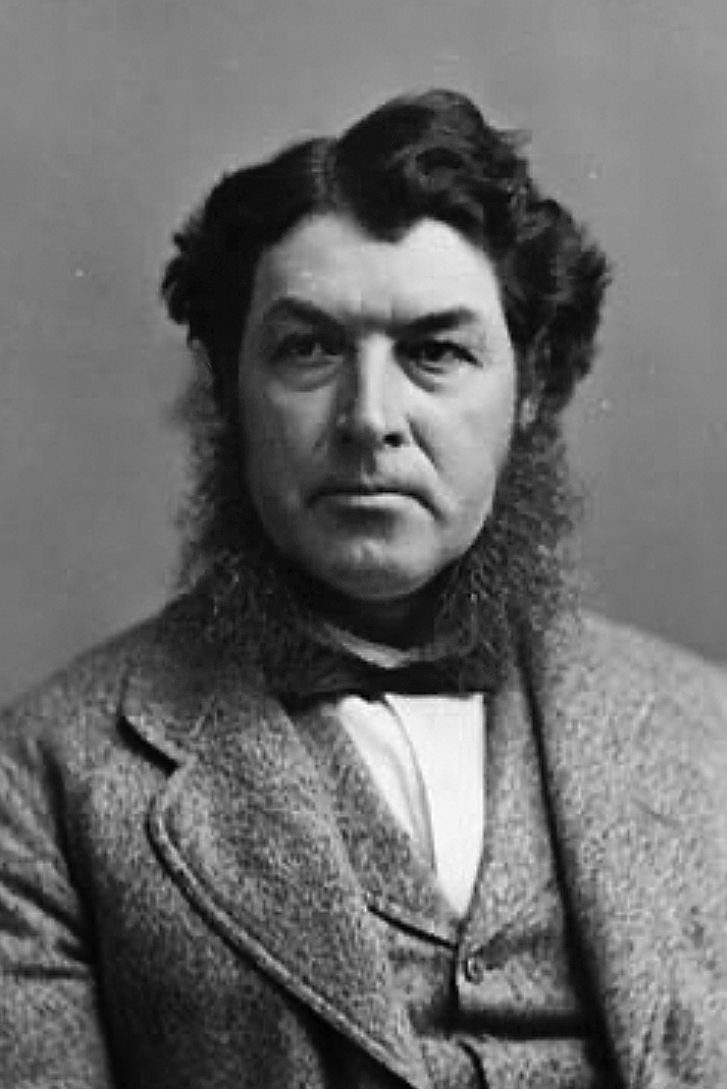

George-Étienne Cartier was one of three leaders — along with Brown and John A. Macdonald — in the Province of Canada’s fragile coalition government.

As the principal voice of French Canada, he argued that granting strong powers to the provinces offered the best insurance that the culture, rights and institutions of minorities — Maritimers as well as French Canadians — would not be swept away in a wave of immigration to central Canada.

“In our own Federation we should have Catholic and Protestant, English, French, Irish and Scotch,” he said. “It is a benefit rather than otherwise that we have a diversity of races.”

The colonies also faced a common threat — the massive military power to the south spawned by the American Civil War. By 1864, the end of the war was in sight, bringing with it the alarming prospect of a combined U.S. army turning its guns northward.

It was critical to unite, Cartier argued, “or be absorbed in an American Confederation.”

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick delegates were focused on one thing: completing the Intercolonial Railway that would connect the Maritimes and central Canada.

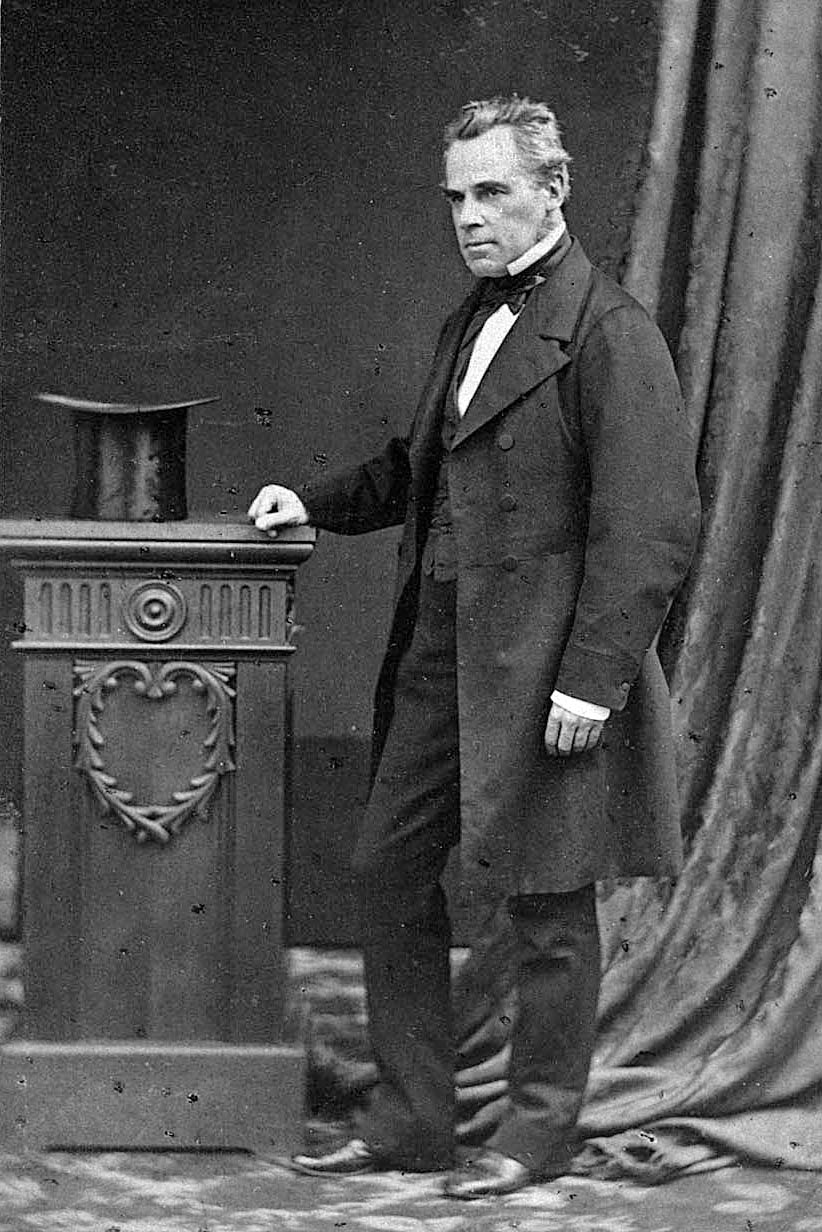

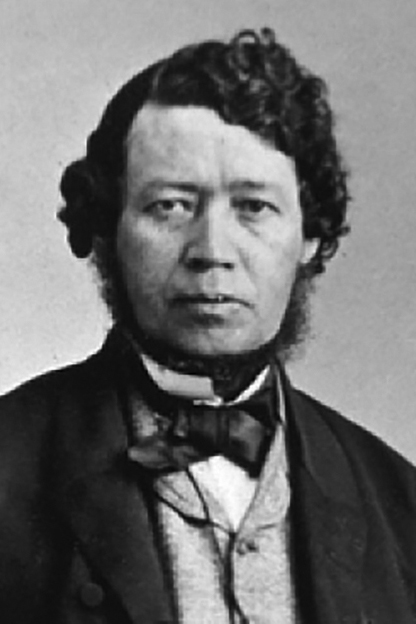

Samuel Leonard Tilley, premier and head of the New Brunswick delegation, put it bluntly: “We won’t have this union unless you give us the railway.”

The Canadians were happy to accommodate. They guaranteed completion of the railway, with Canadian taxpayers covering five-sixths of the cost.

For his part, George Brown was preoccupied with electoral reform. At the time, largely francophone Canada East elected an equal number of parliamentary representatives as anglophone Canada West, despite its lower population. It was, Brown felt, an injustice that must be remedied by entrenching representation by population in the constitution.

But if rep by pop was to be a prerequisite of Confederation, delegates realized that regional and minority interests would have to be protected. French Canada and the Maritime colonies dreaded entrusting decisions of national interest entirely to the majority.

The solution was an upper house of Parliament. There would be two chambers, as in Britain. Unlike its House of Lords, however, Canada’s appointed upper house would be the voice of regions and minorities rather than of traditional aristocratic privilege.

John A. Macdonald, the third partner in the Province of Canada’s coalition government and Canada’s first prime minister, had firm ideas about the Upper House’s role. “It must be an independent house, calmly considering the legislation initiated by the popular branch and preventing any hasty or ill-considered legislation which may come from that body,” he said, “but it will never set itself in opposition against the deliberate and understood wishes of the people.”

In this way, Canada’s Senate would be a counterbalance to the elected House of Commons, a safeguard against the marginalization of minorities and less populous regions. Seats would be allocated according to the principle of regional equality, the details of which would be worked out at the Quebec Conference a month later.

The Maritimers were on board, with the exception of P.E.I. The tiny colony saw little advantage in joining such a mammoth union as a junior partner. (Financial woes would eventually force it to reconsider.) Indigenous peoples were also absent from the final agreement, having been left out of the consultations entirely. That omission left divisions and injustices that are still felt today.

During those heady days in Charlottetown, Confederation had grown from an abstract idea to an inevitability thanks to a pervasive spirit of optimism, friendship and compromise.

“A glorious era lies before us,” Georges-Étienne Cartier said. “We are entering Confederation.”

Negotiations mainly took place in Province House’s legislative council chamber. (Photo credit: Parks Canada)

Negotiations mainly took place in Province House’s legislative council chamber. (Photo credit: Parks Canada)

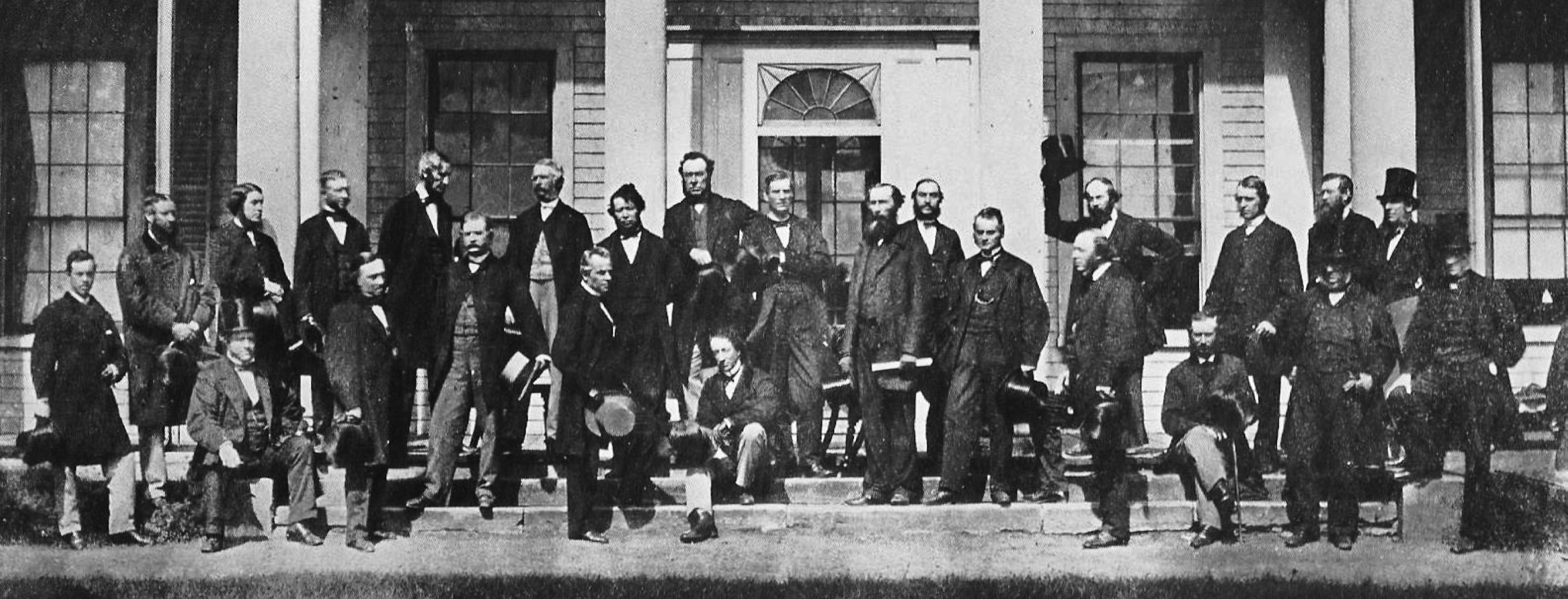

The Fathers of Confederation: Delegates at the 1864 Charlottetown Conference pose for a group portrait in front of Government House, where they attended a banquet and ball hosted by Lieutenant Governor George Dundas. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

The Fathers of Confederation: Delegates at the 1864 Charlottetown Conference pose for a group portrait in front of Government House, where they attended a banquet and ball hosted by Lieutenant Governor George Dundas. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)