Finesse and brute force: The artist behind the Senate of Canada Building’s bronze doors

Anyone who passes through the Senate of Canada Building’s south entrance can’t help but be impressed — and a little overwhelmed — by two shimmering monoliths that tower over the visitor.

Yet few people know they exist.

A set of hammer-formed bronze doors, created 50 years ago by Ottawa sculptor Bruce Garner, embellishes the south entrance to the building.

The entryway, which gives senators direct access to the Senate of Canada Building, is not normally accessible to the public.

The doors were installed in the spring of 1973 as the 60-year-old structure was being converted into a broadcast and hosting venue that would become known as the Government Conference Centre.

“Bruce took the same approach with those doors he did with every sculpture he created,” Tamaya Garner, the artist’s widow and long-time collaborator, said.

“He poured his blood and sweat into them.”

“He always said he left a little bit of himself in every work of art he produced.”

When they were unveiled, the doors — known as Reflections of Canada — were immediately the centre of international attention.

Queen Elizabeth admired them during her July 1973 Royal Visit.

Two days later, 24 world leaders passed through them as they arrived for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, where a ban on nuclear weapons testing dominated the discussion.

For four decades, the building hosted international conferences and federal-provincial first ministers’ talks.

In 2013, after years of slow decline, it received a new lease on life when the Senate chose to temporarily relocate there while Centre Block, its permanent home, underwent extensive restorations.

The Senate-supervised rehabilitation revived much of the former train station’s early 20th-century grandeur. Most fixtures from the 1970s were stripped out, with the notable exception of Mr. Garner’s bronze doors, which heritage appraisers described as distinctive and irreplaceable.

“Bruce always delivered more than the client expected,” Ms. Garner said. “During the initial presentation, the architect went into shock when he realized Bruce was talking about double doors nearly 20 feet high. Bruce didn’t bat an eye. He said, ‘You wanted ceremonial doors. I gave you ceremonial doors.’”

Mr. Garner’s exuberant abstract sculptures have become part of the fabric of Ottawa. Characterized by elongated figures dancing, running, leaping and flying, they dot the city, radiating a whimsical charm Canadians don’t immediately associate with the country’s buttoned-down capital.

“Bruce wanted people to feel at ease around his sculptures and engage with them,” Ms. Garner said. “Nothing made him happier than to see, for instance, one of the figures burnished smooth from people constantly touching it.”

Born in Toronto, Mr. Garner studied at the Ontario College of Art and the University of Alberta. He worked as a graphic designer in Toronto and Vancouver, then moved to Edmonton in the early 1960s to become creative director at what was then Western Canada’s biggest advertising firm, James Lovick & Co.

He moved to Ottawa in 1967 to head up graphic design for the Department of Trade and Commerce.

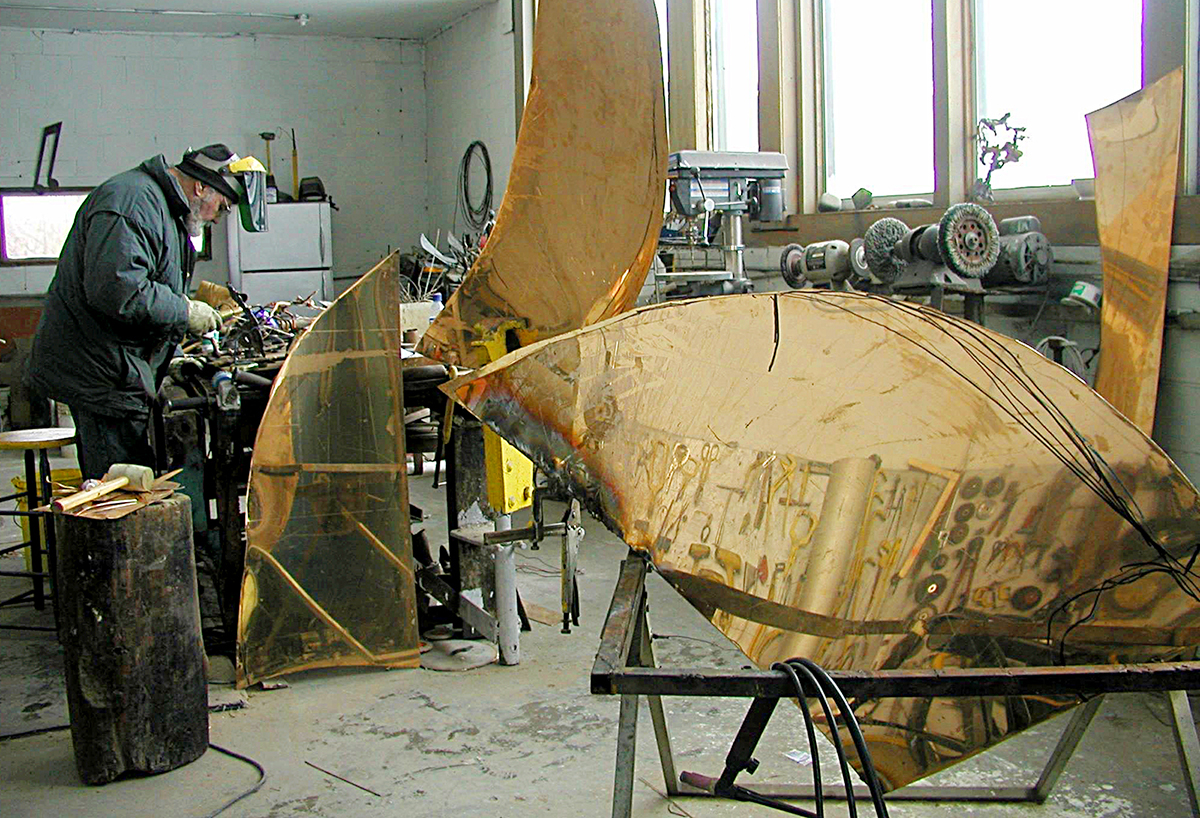

In 1970, he gave up the life of a federal public servant to commit himself full time to sculpture, setting up in a former auto-repair shop in Ottawa’s Chinatown.

A few years later, he moved the studio into a converted barn in rural Plantagenet, 70 kilometres east of Ottawa.

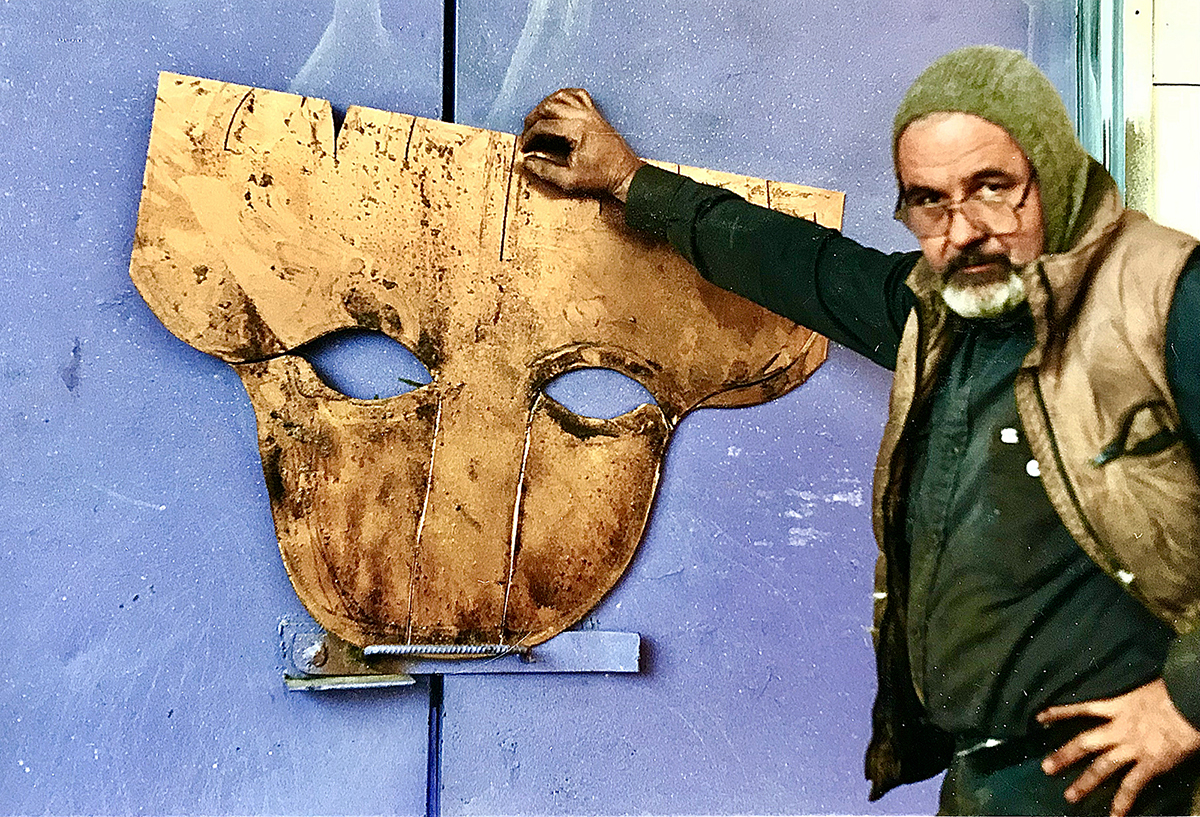

Mr. Garner’s work combined finesse and brute force. He wielded an arsenal of hammers, lathes, grinders, band saws and welding torches to twist steel, copper and bronze into shape.

Newspaper articles described him as a “bear of a man.”

“Bruce was a paradox,” Ms. Garner said. “Here was this powerful, muscular guy whose hands could swing a 50-pound hammer and bend steel. At the same time, those hands could do the most delicate chalk drawings.”

“Bruce used to say he had the soul of a 98-pound ballerina.”