IN PICTURES: Disassembling the woodwork in the Red Chamber and Senate Reading Room

In February 2019, the Senate moved to the Senate of Canada Building, a former train station built in 1912. The Senate will occupy this temporary location while Parliament’s Centre Block — the Senate’s permanent home — is rehabilitated.

Although Centre Block is shuttered for rehabilitation work, Canadians can still experience its art and architecture through the Senate’s immersive virtual tour.

Heritage conservators and skilled carpenters have been carefully dismantling decorative woodwork in Centre Block.

The goal is to remove the woodwork while keeping it as intact as possible, to safeguard it for long-term storage and — in some cases — to restore it while Centre Block is rehabilitated.

This massive job has unfolded over months. It requires extensive research, meticulous cataloguing, expertise in heritage construction and conservation… and finally, patience.

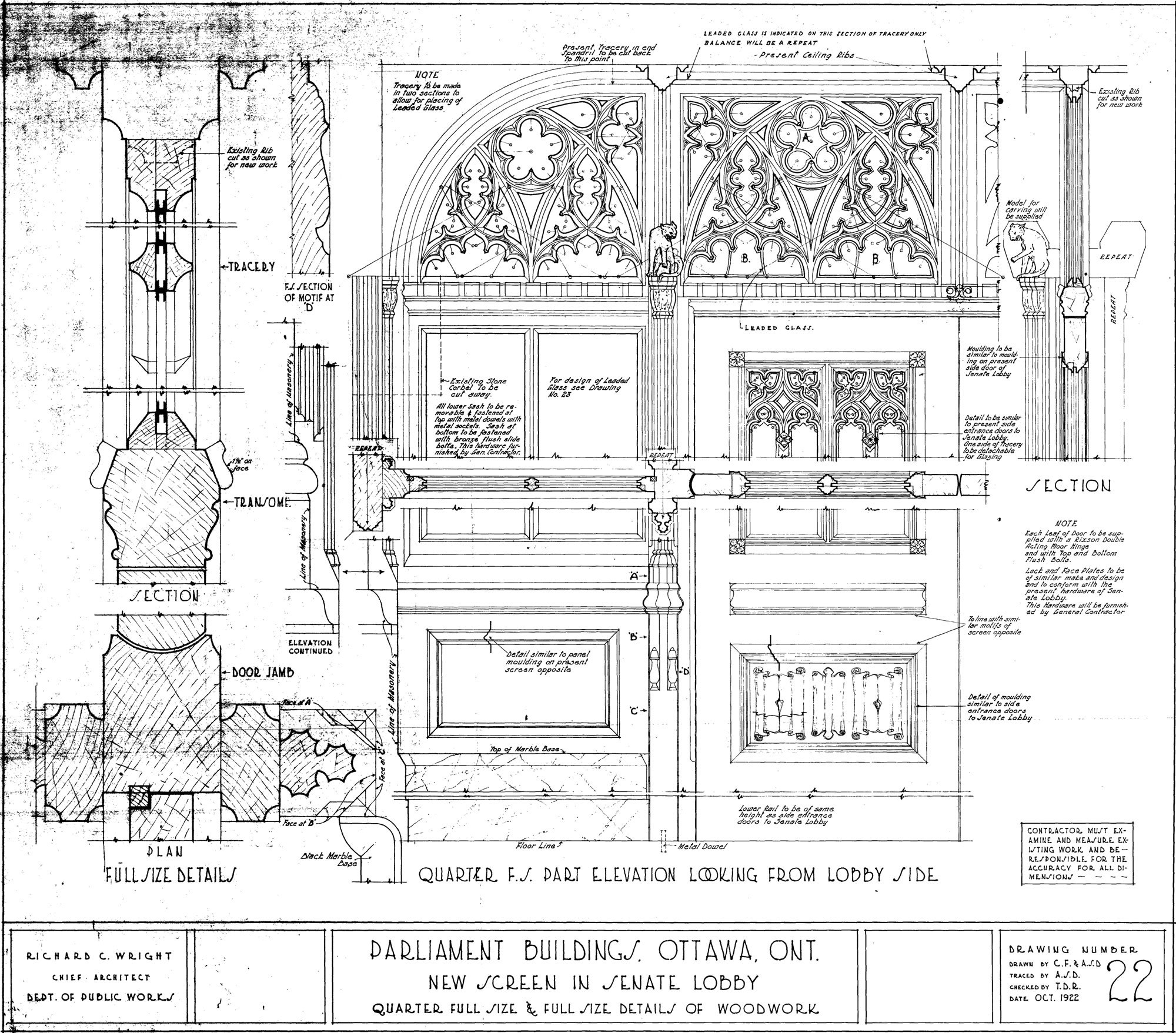

Like Centre Block itself, the woodwork is approximately 100 years old. With none of the original builders around to consult, conservators have had to pore over historical documents to thoroughly grasp the vision of the building’s architect, John A. Pearson. They’ve had to solve the puzzle of how the woodwork was assembled and installed, work backwards for the removal and leave behind clear instructions for how to put it all back together.

“It’s an amazing opportunity for us to obtain firsthand knowledge of how this all came together 100 years ago and to have the best possible chance to reestablish that down the road,” said Sam Pollock, conservator at Heritage Grade.

“That’s a really special thing.”

Keep scrolling for a behind-the-scenes look at the removal of the delicate woodwork in the Red Chamber and the Senate Reading Room.

Workers remove a wooden wall panel in the Senate Reading Room, a space where senators would traditionally go to read newspapers and have a bite between sittings and committee meetings. Through the removal process, conservators determined that most of the woodwork in this room underwent modifications in the 1970s. While they don’t know the complete scope of the renovations, physical evidence showed that many of the original, white-oak veneered boards within the wall panelling had been replaced.

In an alcove in the Senate Reading Room, conservators are surprised and delighted to find the original ceiling underneath the dismantled contemporary one. Heritage Grade conservator Emily Leonoff took a small sample of the original varnish, which will go to a laboratory for testing. “Under the microscope, they’ll figure out what the layers are, and they’ll give us the most modern equivalent,” Ms. Leonoff said. (Photo credit: Heritage Grade)

Workers take great care not to pull out the nails and screws holding the woodwork in place, because doing so could potentially damage the wood. Instead, they use a small pry bar to open the joints of the woodwork just enough to insert a thin hacksaw blade and sever the nail from behind.

Carpenters remove wood panels from a window surround in the Senate Reading Room. To identify which panels to take off, they used a metal detector to find the fasteners, which helped them pinpoint the nails to sever.

A worker from Heritage Grade holds a protective flat board against the wood frame at the top of the window surround as he slips a hacksaw blade underneath the wood to sever the nails.

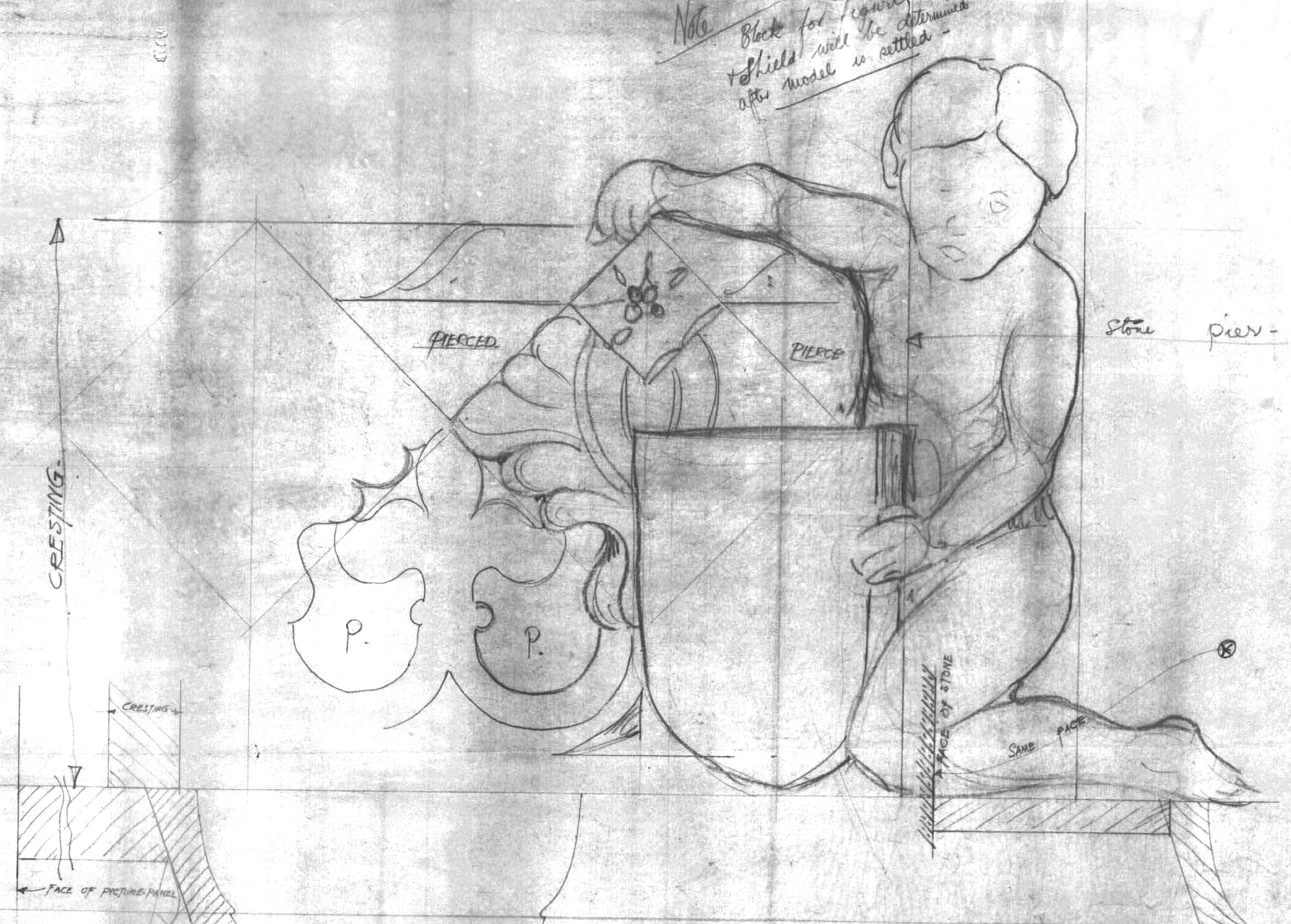

Over in the Senate Chamber, 16 cherubs made of solid white oak crouch among the stone columns and wooden fretwork on the east and west walls. The cherubs are among the interior decorative woodwork produced by Parliament’s carving workshop, run by Cléophas and Elzéar Soucy between the 1920s and 1940s. Because the Chamber’s woodwork had to be dismantled in the reverse order in which it was assembled, the grinning cherubs were some of the first pieces to come down.

A line sketch from the 1920s depicts a cherub and the fretwork cresting in the Senate Chamber. Removing the cherubs proved easier than expected — most were attached with just a few nails. (Photo credit: Heritage Grade)

Workers carefully lower a long section of detached wooden fretwork. Featuring intricate crests, fleurs-de-lis and rosettes, this fretwork is the upper pattern of the frieze that wraps around the Senate Chamber. (Photo credit: Heritage Grade)

Dismantling the woodwork sometimes reveals little treasures from the past, including tightly wound wood shavings, known as “wood curls.” These were a product of last-minute modifications to the wood by the original builders, after the assembled pieces were brought on site for installation. Sometimes, only a few millimetres had to be planed off for the piece to fit just right. (Photo credit: Heritage Grade)

Once catalogued and dismantled, the removed woodwork is brought to a staging area so it can be protected by a packing team before its journey to a climate-controlled storage facility.

Conservators referenced existing original blueprints for the Senate Chamber in Centre Block to best understand Mr. Pearson’s vision of the woodwork and how it was assembled. This blueprint, dated October 1922, maps out the oak screen between the antechamber and the Senate Chamber. (Photo credit: Heritage Grade)