Unwedded Bliss: The Divorce Act, the Senate and a victory for women

When love soured a century ago, divorce was an option — but men and women weren’t treated equally under the law until the Senate stepped in.

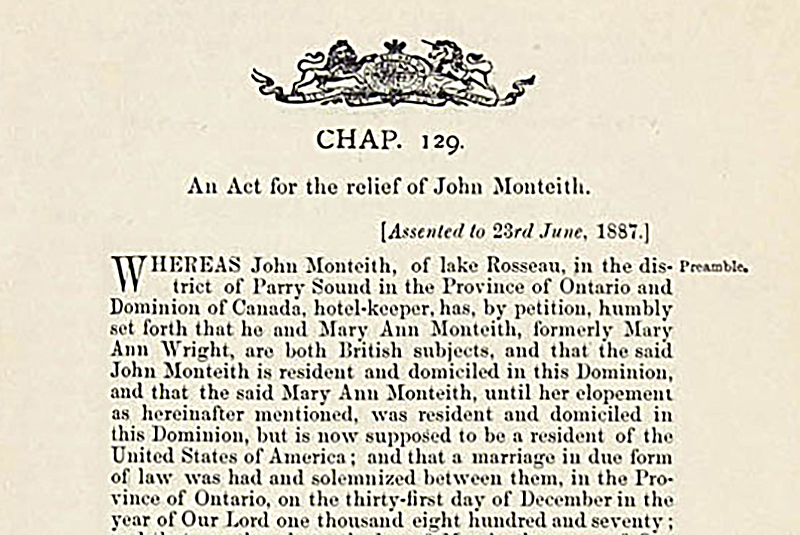

Back then, the state had a prominent place in the bedrooms of the nation. The Senate served as divorce court for much of the country, hearing salacious tales of trysts and betrayals from couples desperate to break the bonds of matrimony through a bill in Parliament.

But where a husband could end a marriage by proving his wife’s adultery, a wife had to prove adultery as well as an additional transgression, such as bigamy, cruelty or desertion.

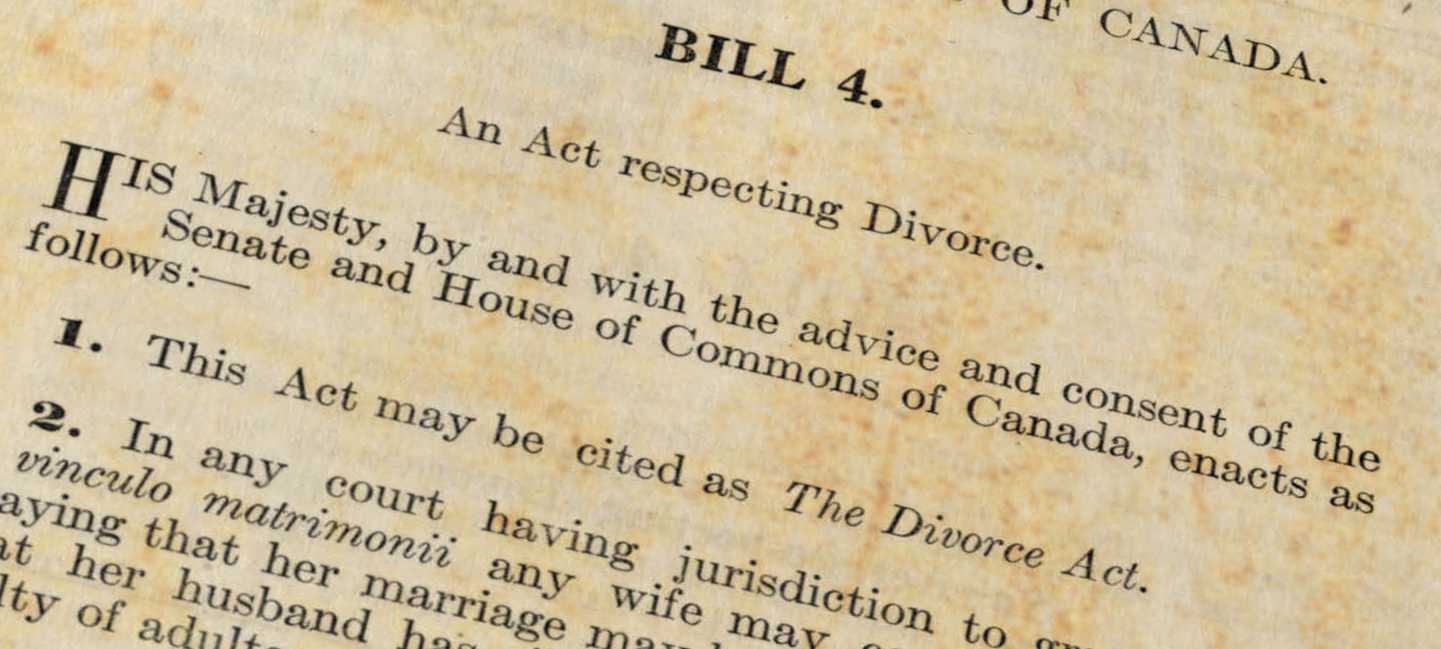

The 1925 Divorce Act established that a woman could obtain a divorce on the same terms as a man. It was the first of many reforms that gradually destigmatized divorce and eventually relieved the Senate from adjudicating matrimonial acrimony.

“It was the beginning of a hard, decades-long struggle,” said Lorna Marsden, a sociologist who has written several books on the history of feminism in Canada.

Dr. Marsden was at the centre of that struggle in the 1970s, as president of the National Action Committee on the Status of Women, before becoming a senator in 1984. Later, she served as president of Wilfrid Laurier University and York University.

Canada’s Constitution had given Parliament the power to legislate on marriage and divorce, but for 58 years it avoided the issue. The foundation of divorce law in the Maritimes and the West, where divorces were granted through specialized courts, remained the United Kingdom’s Matrimonial Causes Act 1857. In Ontario and Quebec, home to more than half the country’s population, there was no divorce law at all: dissolving a marriage meant petitioning Parliament.

It was an exhausting process. Each case went forward as a private bill, requiring testimony before a Senate committee and votes in both houses of Parliament. Senators handled up to 150 petitions a year, debating every one as a separate bill.

“Imagine the obstacles facing an abandoned wife with children who wanted a divorce,” Dr. Marsden said. “She had to travel to Ottawa, find accommodation and appear in front of the Senate. All the time she had to get somebody to look after her children. It was financially out of reach for most women.”

Cases often bogged down in lengthy debate over the fundamental morality of divorce. Senators began to question whether this was a good use of the Chamber’s time.

Speaking in 1887, as a case dragged into its fifth day, Senator William Johnston Almon voiced a frustration many of his colleagues shared.

“The lawyers in the House,” he said, “have spoken one after the other until we, who want to get at the solid business of the country, are tired of it.”

“If we were to adjourn and allow the lawyers to meet in a private committee and talk themselves blind, and then, when they have done that, to meet again and go on with the business of the country, it would be better.”

By 1925, the Senate had dealt with thousands of divorce cases. Over time — and despite any formal legislation to guide it — it had begun treating men and women equally in practice, keeping pace with similar reforms in the U.K. The Divorce Act cemented these reforms in Canada.

Some senators opposed the bill on religious and moral grounds. Senator Thomas Chapais called it a “mischievous, anti-Christian and antisocial law” and a “retrogression to paganism.”

Others, like Senator George Henry Barnard, argued the bill simply recognized gains women had made on other fronts.

“Today the woman has the vote and has been placed on a political equality with man,” he said.

“I consider it only fair and just that in what to her, as to man, is the most important relation in life, she should be placed on a parity with man.”

The legislation passed decisively, 43 to 14, sowing the seeds of reforms that bore fruit in the 1960s.

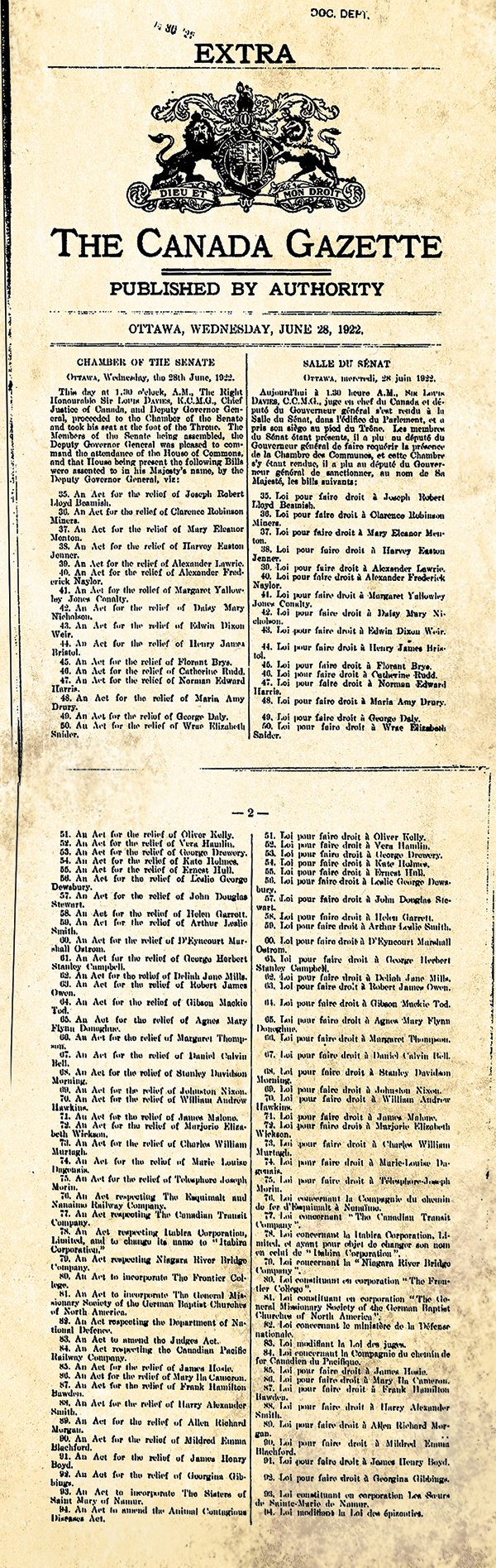

In 1930, Ontario courts were empowered to grant divorces, with desertion added as grounds. A 1963 law streamlined proceedings, allowing divorces to pass by simple Senate resolution instead of full legislation.

“It was a long process,” Dr. Marsden noted. “But there was always this grinding toward reform.”

In 1966, a special joint committee of the Senate and the House of Commons examined divorce reform. The lone woman on the committee was Senator Muriel McQueen Fergusson of New Brunswick, who would become the first female Speaker of the Senate. She ensured women’s advocacy groups were heard.

“She was determined,” Dr. Marsden said. “She might not have used the word ‘feminist,’ but she was a very effective advocate for women and had been all her life.”

Two years later, the Divorce Act of 1968 established a single national law that treated husbands and wives equally and transferred jurisdiction to the provinces. The Senate’s long, often cumbersome role in dissolving marriages was finally over. For many senators, it was a relief. For Canadian women, it was the culmination of a legal journey that began with one forward-looking bill in 1925.

For more information about marriage and divorce records, visit Library and Archives Canada’s Marriages and Divorces resource page.

Senator Muriel McQueen Fergusson, the Senate’s first female Speaker, sat on the 1966 Special Joint Committee on Divorce that drafted Canada’s first national divorce law, the Divorce Act of 1968.

Senator Muriel McQueen Fergusson, the Senate’s first female Speaker, sat on the 1966 Special Joint Committee on Divorce that drafted Canada’s first national divorce law, the Divorce Act of 1968.