Visionary Genius: The artisans who built Centre Block in stone, wood and iron

In February 2019, the Senate moved to the Senate of Canada Building, a former train station built in 1912. The Senate will occupy this temporary location while Parliament’s Centre Block — the Senate’s permanent home — is rehabilitated.

Although Centre Block is shuttered for rehabilitation work, Canadians can still experience its art and architecture through the Senate’s immersive virtual tour.

Centre Block — home to the Senate of Canada and the House of Commons — went up in flames on the night of February 3, 1916.

“Canada’s Parliament Buildings Destroyed,” the Ottawa Evening Journal proclaimed the next day. “Great Edifice of Confederation is To-day Mere Heap of Smouldering Ruins.”

It was a crushing blow to a cash-strapped country embroiled in the First World War and reeling from the loss of over 10,000 Canadians on the Western Front.

But the government of Robert Borden resolved to rebuild. Within seven months, architects had been chosen, plans drawn up and the salvaged cornerstone of the original building relaid at the northeast corner of Parliament Hill.

“The fire offered an unusual moment of opportunity,” House of Commons Curator Johanna Mizgala said.

“In the 50 years since Confederation, Canada had expanded enormously and had essentially outgrown the original Centre Block. Suddenly they had the opportunity to think, ‘What if we had a larger structure? What if we did some things differently?’”

The rebuild succeeded in bringing together four of the most remarkable craftsmen the country has ever produced. During the 1920s and 30s, they were responsible for many of the decorative features that make Centre Block one of the world’s most instantly recognizable buildings.

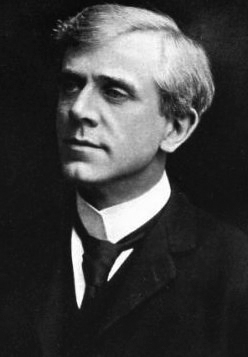

THE VISIONARY

John A. Pearson

Chief architect John A. Pearson was a perfectionist. He personally managed every detail of the building’s construction — from the ground plan and furniture design, to the symbolism of its statues and ornaments.

“Everything was designed to act together as a cohesive whole,” Ms. Mizgala said. “Pearson conceived the building as a total work of art.”

Pearson chose the stone for Centre Block’s interior in consultation with William Parks, a celebrated University of Toronto geologist. Parks recommended Manitoba Tyndall, a cream-coloured limestone with a subtle mottled texture and occasional fossil traces.

“The carvers working under Pearson protested,” said Dominion Sculptor Phil White. “They complained it was too coarse for fine carving, so Indiana limestone — a smooth stone with virtually no grain — was substituted for pieces that required a particularly fine touch.”

Pearson’s obsession with detail caused friction with some of the people he hired. Walter Allen, who headed the sculpture workshop, left in 1924. His replacement, Ira Lake, completed most of the sculptures in the Peace Tower’s Memorial Chamber but abruptly resigned in 1927, complaining of Pearson’s insistence on adding “meaningless Gothic foliage” to Lake’s designs.

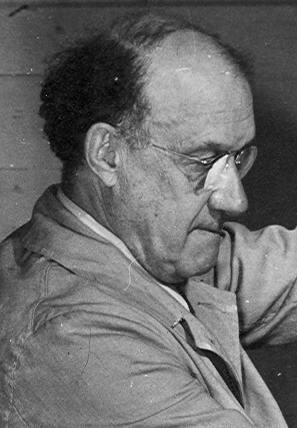

THE SCULPTOR

Cléophas Soucy

Lake was replaced by Montrealer Cléophas Soucy, who had been with the Centre Block sculpting team since 1919. Having contributed to every stage of the project, Soucy was seen as the man who best understood Pearson’s vision; he became Parliament’s first Dominion Sculptor.

“Soucy knew the building and the history of the program. He embodied its institutional memory,” said Mr. White who, as Dominion Sculptor, is in charge of the program Soucy once headed.

Soucy supervised a team of as many as 13 carvers. They worked on and off through the 1930s and 40s, completing most of the building’s exterior as well as the Senate and House of Commons chambers. During the summer months, his team rushed to complete as much work as possible while Parliament was in recess.

THE CARVER

Elzéar Soucy

Elzéar Soucy was Cléophas Soucy’s older brother. He was in charge of much of the interior woodwork and worked on the Senate and House of Commons chambers between 1920 and 1928. Until then, he had been best known for his bronze statue of French soldier and colonial administrator Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville outside the Parliament Building in Québec City.

“Elzéar and his team carved mainly in white oak,” said Mr. White. “It’s a durable, beautifully fine-grained wood. It’s perfect for a Gothic Revival building like Centre Block because it’s the wood medieval sculptors used.”

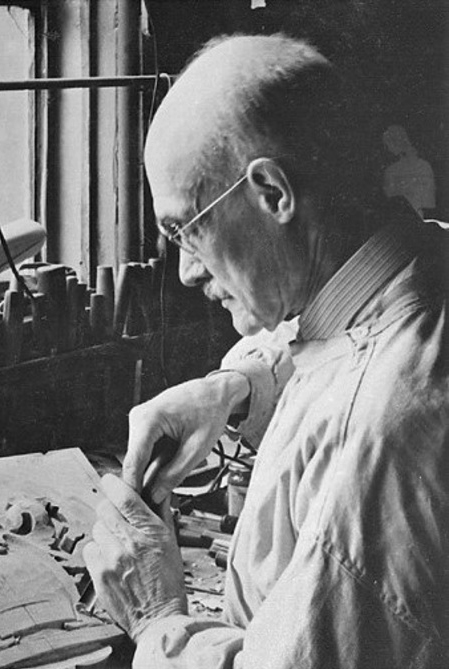

THE LOST GENIUS

Paul Beau

The fourth man to put his stamp on Centre Block’s interior was iron master Paul Beau. Beau began his career as an antiques dealer and watchmaker before branching into fine metalwork. Largely self-taught, he learned the craft of working copper, brass and iron during antique-buying trips abroad, studying museum collections in Paris, New York, London and Brussels.

He produced interior furnishings for some of Montréal’s grandest homes and was commissioned in 1910 to produce decorative ironwork for Saskatchewan’s legislative building.

In 1920, John Pearson hired Beau to head up Parliament Hill’s iron workshop. For six years, Beau and his assistants produced a stunning array of iron fixtures including fireplace utensils, ornamental door hinges, railings and balconies.

“No craftsman at the time could match his skill,” Mr. White said. “He was one of the few contractors hired without competition.”

But Beau was a consummate craftsman at a time when industrialization was making wrought-iron work obsolete. The Centre Block commission and one in the 1930s for the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts kept him going for a time until the Second World War dealt the final blow.

“The war was devastating,” Mr. White said. “Demand dried up for his decorative metal wares. The iron, copper and brass he needed had been appropriated for wartime manufacturing.”

Destitute and forgotten, the 78-year-old Beau took his own life under the steel cross on Montréal’s Mount Royal.

A legacy of stone, wood and iron

Centre Block’s carvings and iron fixtures are being painstakingly safeguarded as construction takes place. Paintings and furniture have been moved into storage. Heritage woodwork, columns and sculptures have been removed or secured behind plywood barriers.

Mr. White reflected on the impact these four remarkable artists have had on Canada’s most iconic building.

“All of them — John Pearson, Cléophas and Elzéar Soucy, Paul Beau — devoted the best years of their careers to Centre Block. The building is one of the most distinctive government buildings in the world because there’s nothing formulaic about it. Each artisan left his personal stamp on it.”