A journeyman’s tale: Canada’s new Dominion Sculptor takes the road less travelled

It’s been a long road for John-Philippe Smith, Canada’s new Dominion Sculptor.

As Parliament’s official carver, the Dominion Sculptor supervises all carving in Centre Block and the Parliamentary Precinct. Six people have held the title since the role was officially created in 1936. The fifth, Phil White, recently retired after 15 years at the helm.

Mr. Smith, who studied at Ottawa’s Algonquin College and at France’s Atelier Jean-Loup Bouvier, joined the parliamentary sculpting team in 2018 and was recently appointed Mr. White’s successor.

How does it feel to be the new Dominion Sculptor of Canada?

It’s still sinking in. I have a lot to learn. Thankfully, I have incredible support from my team and from our parliamentary partners.

You first joined the parliamentary sculpture team in April 2018. How did that come about?

Two sculptural assistants were chosen as part of a national competition: myself and my colleague Nicholas Thompson.

Luckily, the selection committee was familiar with my work. Phil White, the Dominion Sculptor at the time, had contracted me to help carve a couple of parliamentary emblems in 2011.

I had all the qualifications on paper: I had the education and training, I had run my own business. I’d managed employees, but what it ultimately came down to was, “Show us your portfolio.”

How did you become a sculptor in the first place?

While I was studying geology at the University of Ottawa, I had a part-time job as doorman at the Fairmont Chateau Laurier.

I stayed with Fairmont Hotels after graduation and eventually ended up in corporate sales at their head office in Toronto. I loved interacting with guests, but the desk job just wasn’t as appealing. I knew my future would just be about moving into bigger and bigger cubicles.

I wasn’t happy. I needed to work with my hands. A colleague who felt the same way was looking at trades and came across heritage stone masonry. I said, “Wow, that sounds interesting!”

Pretty soon after, I enrolled in Algonquin College’s heritage masonry program.

Once you graduated, what direction did your career take?

I worked for about 10 years in Canada but knew that something was missing.

Then I found out about this program that allows young people between the ages of 18 and 35 to work abroad on a one-year visa. I was just about to turn 35 so I said, “Okay, I have to do this now.” I got my visa and moved to France.

For two weeks, I roamed the streets of Paris, scouting every job site, listening for the sound of hammers and chisels. I’d look down alleyways to see if there was masonry work going on, then go and talk to the foreman.

I had researched the top companies before I left. Number one on my list was Atelier Jean-Loup Bouvier, but I honestly thought, “There’s no way they’re going to hire me.”

One day, I saw Jean-Loup Bouvier’s van in front of Notre-Dame cathedral. I had my portfolio and I approached this gentleman with an enormous French moustache.

I guess he really took a shine to my Québécois accent. He said, “Follow me.” We hopped on a bus and rode through the streets of Paris to the Opéra Garnier.

He brings me up on a scaffold and says, “Can you carve this volute?” Everything in me wanted to, but I told him, “I can’t do this. If I start, I’ll be bugging one of your guys constantly for help.”

I turned him down and walked away. That night I didn’t sleep. I was thinking, “You just blew your one and only chance.”

Soon after, I saw a notice that somebody in the south of France was looking for a sculptor. I went and talked to this gentleman who was opening a high-end jewellery store and had a bunch of stone capitals to carve. I showed him my portfolio and he said, “I’ll hire you right away.”

“Great, who am I working with?”

He says, “Oh no, you’ll be working by yourself.” I said, “Listen, I came here to learn from French carvers. If I’m not working with anybody else, I can’t do it.” So, here I am turning down a second amazing opportunity. That was another sleepless night.

I remember jumping out of bed at 3 a.m. in the morning, thinking, “I’ve got it! I’ll call Jean-Loup Bouvier and tell him I found him a job. Would he be willing to hire me on to do it?”

I called him the next day and he thought that was hilarious. He said, “Why don’t you come down here and work with our team?” Two days later, I was on the TGV on my way to Avignon.

Has it been a smooth transition into the Dominion Sculptor role?

I was lucky to have had the chance to work for three years under Phil White. He is a truly incredible sculptor.

He set me up perfectly. A lot of it was just watching how he approaches things on the tools and off the tools.

I watched how, in meetings, he’s always very patient and thoughtful, how he solves problems.

He taught me to understand the inner workings of government. He made sure that the program was on solid foundations before he left.

What are your immediate plans for the parliamentary sculpting program?

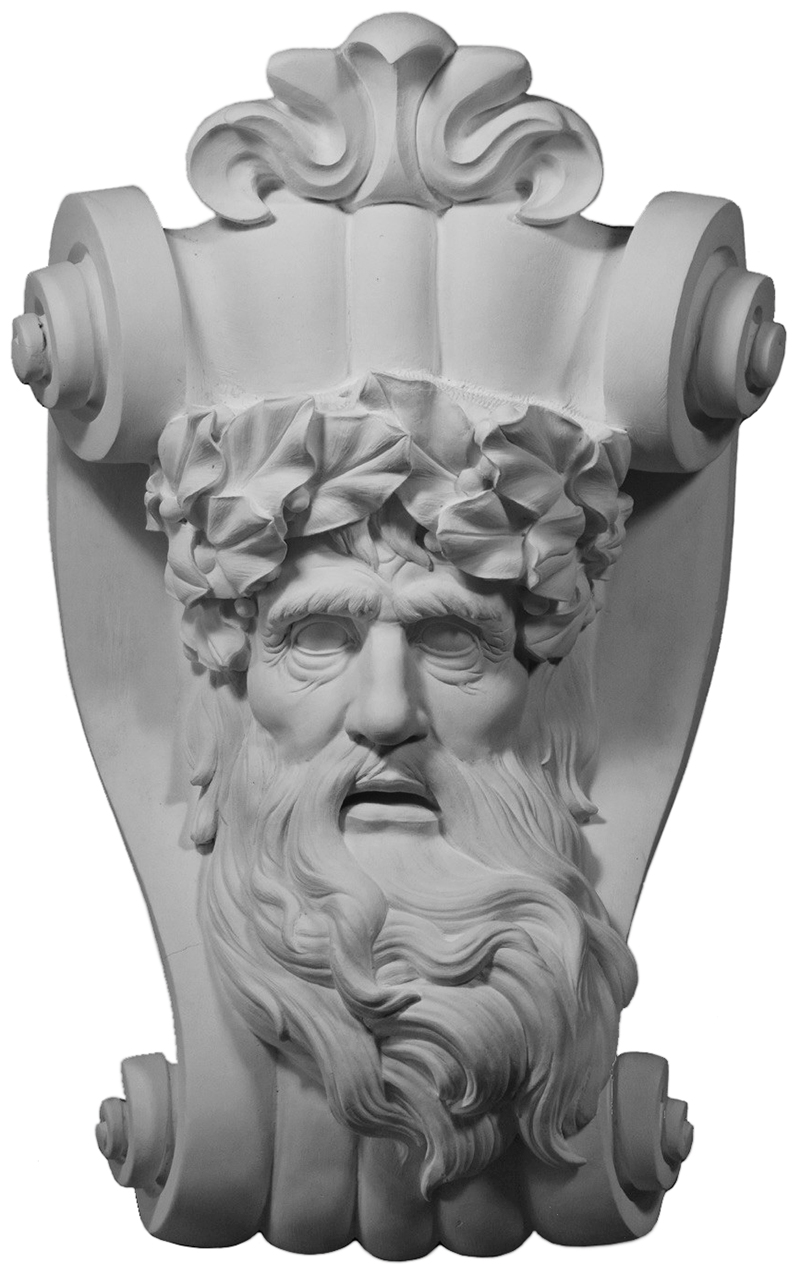

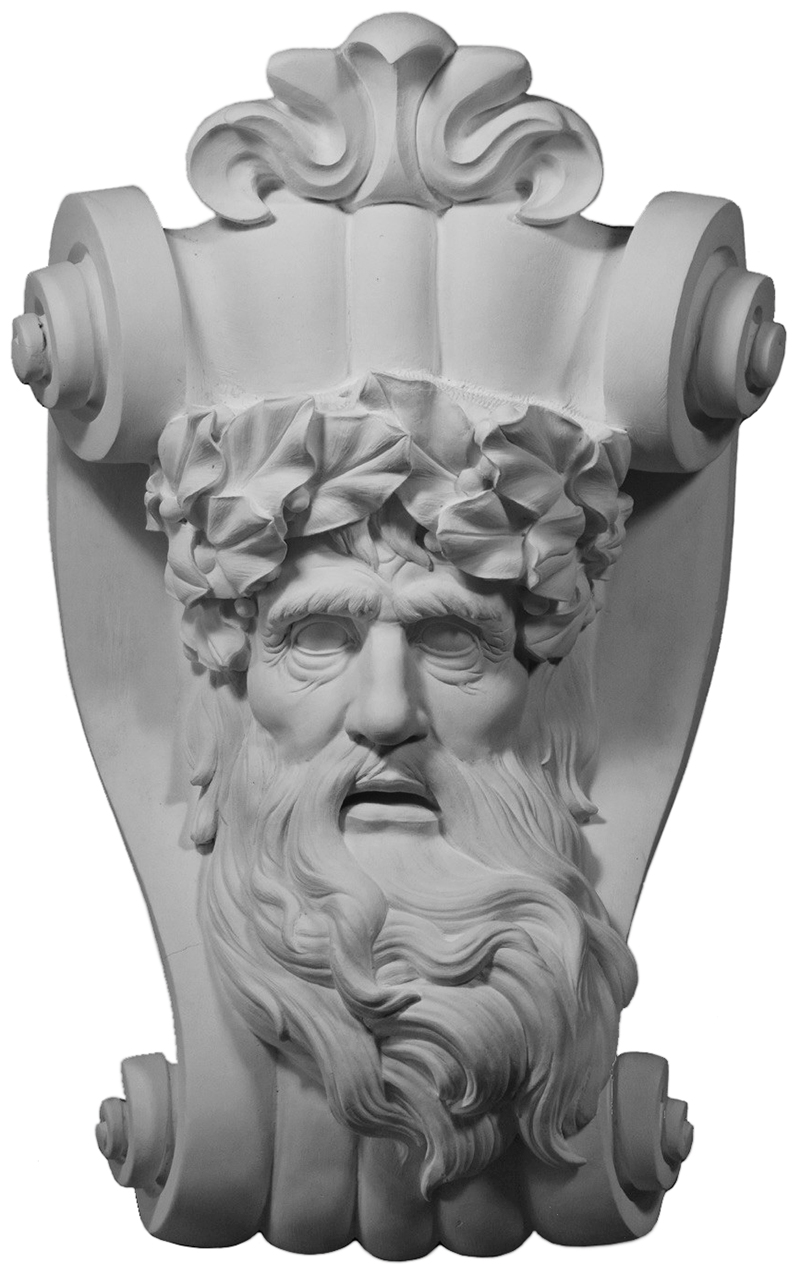

The Centre Block rehabilitation offers an opportunity to carve stones in very difficult-to-reach areas when there’s no parliamentary business going on.

There are 188 blocks that remain uncarved in Centre Block, so we’re looking at completing some of those as well as doing restoration work.

Those fantastic sculptures on the exterior date from the building’s construction a hundred years ago and many need to be repaired or replaced.

What about the long term?

If you love your trade, you want it to be there forever. You want it to grow stronger. Teaching the next generation is a long-term priority.

If you have a dedicated team that passes skills along, then everyone benefits. The carvers benefit, the Parliamentary Precinct benefits from their expertise and Canadians benefit, knowing their Parliament will continue to be well taken care of.

Related articles

Tags

Committee news

A journeyman’s tale: Canada’s new Dominion Sculptor takes the road less travelled

It’s been a long road for John-Philippe Smith, Canada’s new Dominion Sculptor.

As Parliament’s official carver, the Dominion Sculptor supervises all carving in Centre Block and the Parliamentary Precinct. Six people have held the title since the role was officially created in 1936. The fifth, Phil White, recently retired after 15 years at the helm.

Mr. Smith, who studied at Ottawa’s Algonquin College and at France’s Atelier Jean-Loup Bouvier, joined the parliamentary sculpting team in 2018 and was recently appointed Mr. White’s successor.

How does it feel to be the new Dominion Sculptor of Canada?

It’s still sinking in. I have a lot to learn. Thankfully, I have incredible support from my team and from our parliamentary partners.

You first joined the parliamentary sculpture team in April 2018. How did that come about?

Two sculptural assistants were chosen as part of a national competition: myself and my colleague Nicholas Thompson.

Luckily, the selection committee was familiar with my work. Phil White, the Dominion Sculptor at the time, had contracted me to help carve a couple of parliamentary emblems in 2011.

I had all the qualifications on paper: I had the education and training, I had run my own business. I’d managed employees, but what it ultimately came down to was, “Show us your portfolio.”

How did you become a sculptor in the first place?

While I was studying geology at the University of Ottawa, I had a part-time job as doorman at the Fairmont Chateau Laurier.

I stayed with Fairmont Hotels after graduation and eventually ended up in corporate sales at their head office in Toronto. I loved interacting with guests, but the desk job just wasn’t as appealing. I knew my future would just be about moving into bigger and bigger cubicles.

I wasn’t happy. I needed to work with my hands. A colleague who felt the same way was looking at trades and came across heritage stone masonry. I said, “Wow, that sounds interesting!”

Pretty soon after, I enrolled in Algonquin College’s heritage masonry program.

Once you graduated, what direction did your career take?

I worked for about 10 years in Canada but knew that something was missing.

Then I found out about this program that allows young people between the ages of 18 and 35 to work abroad on a one-year visa. I was just about to turn 35 so I said, “Okay, I have to do this now.” I got my visa and moved to France.

For two weeks, I roamed the streets of Paris, scouting every job site, listening for the sound of hammers and chisels. I’d look down alleyways to see if there was masonry work going on, then go and talk to the foreman.

I had researched the top companies before I left. Number one on my list was Atelier Jean-Loup Bouvier, but I honestly thought, “There’s no way they’re going to hire me.”

One day, I saw Jean-Loup Bouvier’s van in front of Notre-Dame cathedral. I had my portfolio and I approached this gentleman with an enormous French moustache.

I guess he really took a shine to my Québécois accent. He said, “Follow me.” We hopped on a bus and rode through the streets of Paris to the Opéra Garnier.

He brings me up on a scaffold and says, “Can you carve this volute?” Everything in me wanted to, but I told him, “I can’t do this. If I start, I’ll be bugging one of your guys constantly for help.”

I turned him down and walked away. That night I didn’t sleep. I was thinking, “You just blew your one and only chance.”

Soon after, I saw a notice that somebody in the south of France was looking for a sculptor. I went and talked to this gentleman who was opening a high-end jewellery store and had a bunch of stone capitals to carve. I showed him my portfolio and he said, “I’ll hire you right away.”

“Great, who am I working with?”

He says, “Oh no, you’ll be working by yourself.” I said, “Listen, I came here to learn from French carvers. If I’m not working with anybody else, I can’t do it.” So, here I am turning down a second amazing opportunity. That was another sleepless night.

I remember jumping out of bed at 3 a.m. in the morning, thinking, “I’ve got it! I’ll call Jean-Loup Bouvier and tell him I found him a job. Would he be willing to hire me on to do it?”

I called him the next day and he thought that was hilarious. He said, “Why don’t you come down here and work with our team?” Two days later, I was on the TGV on my way to Avignon.

Has it been a smooth transition into the Dominion Sculptor role?

I was lucky to have had the chance to work for three years under Phil White. He is a truly incredible sculptor.

He set me up perfectly. A lot of it was just watching how he approaches things on the tools and off the tools.

I watched how, in meetings, he’s always very patient and thoughtful, how he solves problems.

He taught me to understand the inner workings of government. He made sure that the program was on solid foundations before he left.

What are your immediate plans for the parliamentary sculpting program?

The Centre Block rehabilitation offers an opportunity to carve stones in very difficult-to-reach areas when there’s no parliamentary business going on.

There are 188 blocks that remain uncarved in Centre Block, so we’re looking at completing some of those as well as doing restoration work.

Those fantastic sculptures on the exterior date from the building’s construction a hundred years ago and many need to be repaired or replaced.

What about the long term?

If you love your trade, you want it to be there forever. You want it to grow stronger. Teaching the next generation is a long-term priority.

If you have a dedicated team that passes skills along, then everyone benefits. The carvers benefit, the Parliamentary Precinct benefits from their expertise and Canadians benefit, knowing their Parliament will continue to be well taken care of.