Retirement, part two: Senator Sinclair bids farewell to the Senate

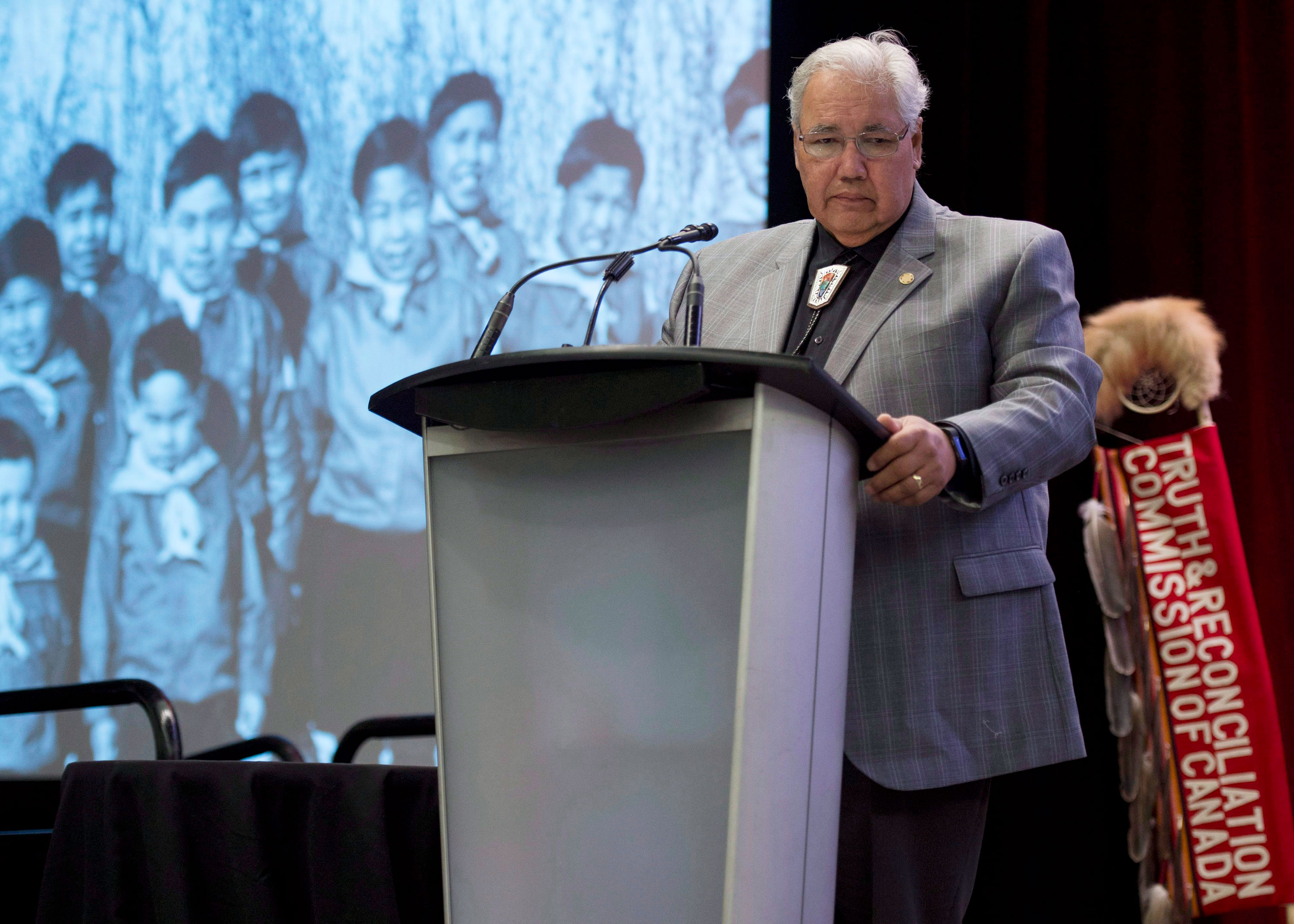

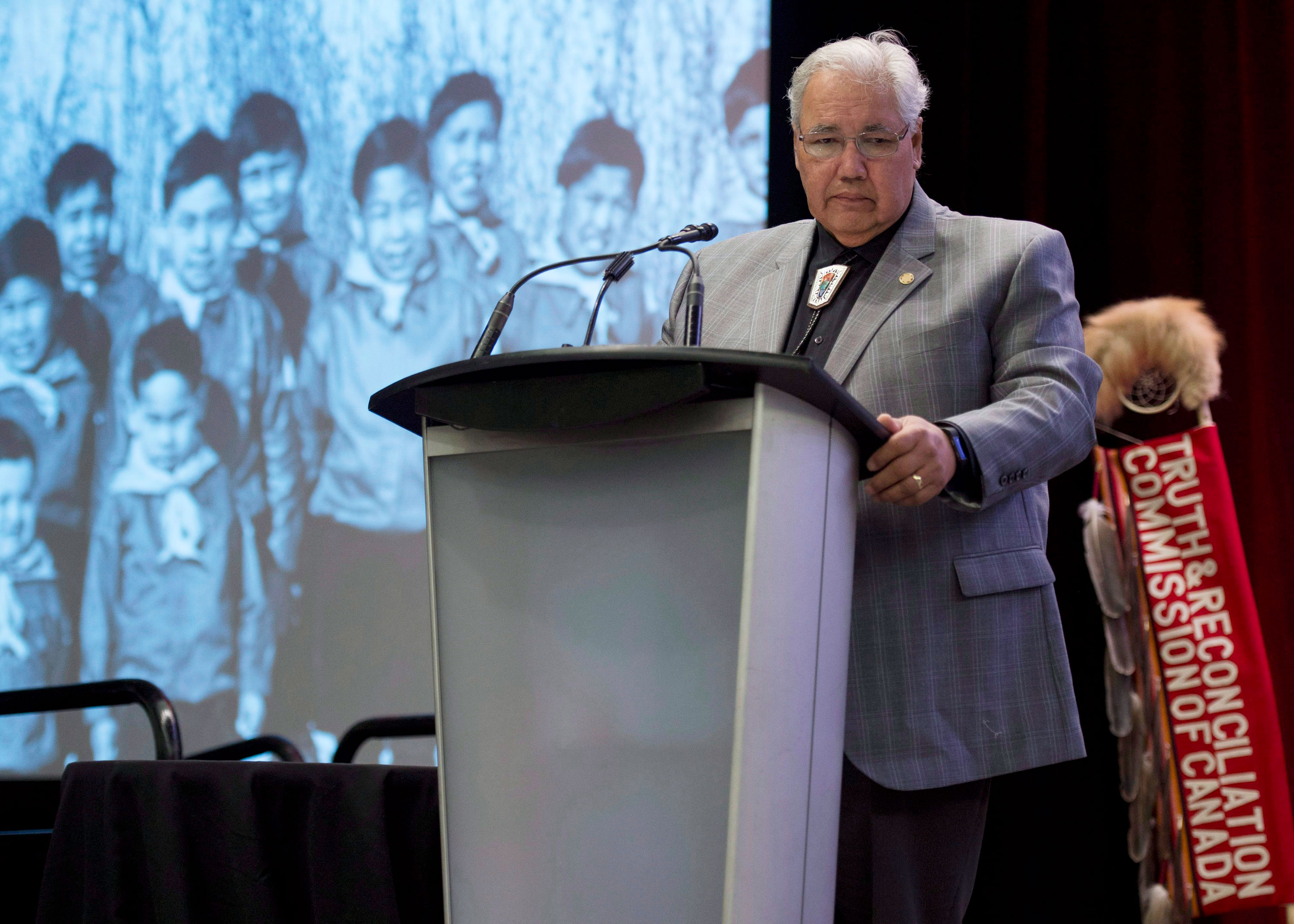

Senator Murray Sinclair was Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge and Canada’s second, but he is perhaps best known for serving as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In that role, he participated in hundreds of hearings across Canada to hear stories from survivors of the residential school system and its lasting effects on Indigenous peoples’ lives.

He was appointed to the Senate in 2016, where he continued to advocate for reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples of Canada. During his five years in the Red Chamber, he served on several committees, including the Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples and the Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs.

SenCAplus asked Senator Sinclair to reflect on his time in the Senate ahead of his retirement on January 31, 2021.

You were appointed to the Senate in 2016. What was your reaction when you received that phone call from the prime minister?

I remind people that when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) ended on December 15, 2015, in my closing remarks I said that it was my intention to withdraw from public life and that it was time for me to start paying attention to my family, and in particular, my wife. She had given up so much of her time for my career and I wouldn’t have been able to do the things that I had been called upon to do without her support.

With that, we closed the TRC down and I handed in my resignation effective January 31, 2016 and that was my last day of being a judge. I spent those first few days walking a lot, taking my dogs for walks and contemplating things. I was actually in the middle of a walk when I got a call from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. I answered it and he said almost right away he’d like to ask if I’d accept an appointment to the Senate. I said, “Well, Prime Minister, you were there at the closing ceremony and heard me say I was stepping back from public life.” He said he wouldn’t ask me if he didn’t think it was important and he explained what his thinking was and why he wanted me in the Senate.

So, I did talk it over with the family and my wife said, “Well, you’ve been retired now for eight days and you organized my cupboards three times. I was going to ask you to get a part-time job anyway.” She said she could probably support this as long I didn’t do it for the rest of my life. I said I’d do it for five years and then I’d re-evaluate.

Is that why you’re retiring early? You could have stayed until 2026!

That was the primary consideration. I made a five-year commitment and I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in the Senate. I thought this was an opportune time with the pandemic and I wasn’t travelling to Ottawa very much in the last year anyway thanks to working virtually. On top of all of that was, of course, my wife’s health has not been good, and she now has greater needs and is more medically vulnerable. I felt that I had accomplished a few things that were worthwhile and that it was time for me to move on and to allow those other Indigenous senators who are now in the Senate to pick up some of that load.

Your son, Niigaan, wrote an affectionate op-ed about your devotion to your community as the first Indigenous judge in Manitoba and as the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. How did those experiences shape your work in the Senate?

The experience of being the chair of the TRC and listening to survivors, working with those who were trying to bring their stories forward so that others could learn from that experience, taught me the importance of leadership. My role as a judge had a great influence on my approach for things. It showed me the true benefits of being able to listen to people before responding to what they’ve said in order to cut through the stress of the dialogue.

The best example is the work I did on Romeo Saganash’s bill on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). That had been a cornerstone of the calls to action of the TRC to get Canadian institutions, including provincial and federal governments, to look at using the UN declaration as a framework to reconciliation.

Being able to explain that to senators, to members of the public and to those who came forward to make submissions on that point — and even those speaking in opposition to the declaration — provided a fine educational opportunity and I think I was able to do that. Now, the government has introduced a government bill to do the same thing. I think it stands to gain more support in the Senate than the original bill did because we did the work to get people to understand what the bill was about, what the declaration was about. Now, that groundwork has all been laid and I think the bill will have a smoother passage through the Senate.

In your maiden speech in the Upper Chamber, you referred to the Senate as Canada’s “council of elders” and said that you accepted the appointment in the hope that you could continue the work of reconciliation through education and understanding. How would you like to see that vision continue?

The Senate should really be looking upon itself as a council of elders for the country and in an image such as that, the vision of a council of elders means that there is no role for partisanship. You have to each speak independently about the future of the country and take the best interests of the country at heart. That includes an approach to reconciliation that is not about protecting interests. It’s a different vision of the Senate that the Senate now holds of itself.

You’re retiring from the Senate with a legacy of advocacy for the natural world. You helped sponsor the bill to end whale and dolphin captivity in Canada, which became law in June 2019, and now you’re attempting to provide the same protection for great apes and elephants. Why is it important to you for Parliament to pass Bill S-218, the Jane Goodall Act?

It’s about setting the tone for the country when it comes to understanding what our relationship is with the other beings of creation. We need to be looking upon other creatures that live with us not only as property and we need to be more respectful of them as true beings. They were put here for a purpose and we need to understand and respect that purpose. The intention was to get people to shift their thinking of the overall approach that we take to animals, that trophy hunting or putting animals on display for entertainment purposes should be condemned. We’re not doing enough in that regard. The purpose of the Jane Goodall Act is to put some parameters around that in recognition of not only that very basic principle, but also in recognition of the role of Jane Goodall.

What advice would you give to the next Indigenous person appointed to the Senate?

To keep in mind that there are many ahead of you now. At the time of this interview, there are 12 Indigenous senators. They all meet regularly about our Indigenous perspective and about things that are happening not only in the Senate, but in the public as well. We call upon members of cabinet to meet with us, to talk to us. We meet with the Indigenous members of the House of Commons to see what kind of collective approach we can take to benefit the Indigenous community. Those senators who are coming after us need to know that there are people who have already shown the way, that there are other Indigenous senators who are already advocating for the kinds of changes that are necessary to achieve reconciliation and that their concerns will not only have support but will be able to continue in the Senate.

Related articles

Tags

Committee news

Retirement, part two: Senator Sinclair bids farewell to the Senate

Senator Murray Sinclair was Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge and Canada’s second, but he is perhaps best known for serving as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In that role, he participated in hundreds of hearings across Canada to hear stories from survivors of the residential school system and its lasting effects on Indigenous peoples’ lives.

He was appointed to the Senate in 2016, where he continued to advocate for reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples of Canada. During his five years in the Red Chamber, he served on several committees, including the Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples and the Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs.

SenCAplus asked Senator Sinclair to reflect on his time in the Senate ahead of his retirement on January 31, 2021.

You were appointed to the Senate in 2016. What was your reaction when you received that phone call from the prime minister?

I remind people that when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) ended on December 15, 2015, in my closing remarks I said that it was my intention to withdraw from public life and that it was time for me to start paying attention to my family, and in particular, my wife. She had given up so much of her time for my career and I wouldn’t have been able to do the things that I had been called upon to do without her support.

With that, we closed the TRC down and I handed in my resignation effective January 31, 2016 and that was my last day of being a judge. I spent those first few days walking a lot, taking my dogs for walks and contemplating things. I was actually in the middle of a walk when I got a call from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. I answered it and he said almost right away he’d like to ask if I’d accept an appointment to the Senate. I said, “Well, Prime Minister, you were there at the closing ceremony and heard me say I was stepping back from public life.” He said he wouldn’t ask me if he didn’t think it was important and he explained what his thinking was and why he wanted me in the Senate.

So, I did talk it over with the family and my wife said, “Well, you’ve been retired now for eight days and you organized my cupboards three times. I was going to ask you to get a part-time job anyway.” She said she could probably support this as long I didn’t do it for the rest of my life. I said I’d do it for five years and then I’d re-evaluate.

Is that why you’re retiring early? You could have stayed until 2026!

That was the primary consideration. I made a five-year commitment and I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in the Senate. I thought this was an opportune time with the pandemic and I wasn’t travelling to Ottawa very much in the last year anyway thanks to working virtually. On top of all of that was, of course, my wife’s health has not been good, and she now has greater needs and is more medically vulnerable. I felt that I had accomplished a few things that were worthwhile and that it was time for me to move on and to allow those other Indigenous senators who are now in the Senate to pick up some of that load.

Your son, Niigaan, wrote an affectionate op-ed about your devotion to your community as the first Indigenous judge in Manitoba and as the chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. How did those experiences shape your work in the Senate?

The experience of being the chair of the TRC and listening to survivors, working with those who were trying to bring their stories forward so that others could learn from that experience, taught me the importance of leadership. My role as a judge had a great influence on my approach for things. It showed me the true benefits of being able to listen to people before responding to what they’ve said in order to cut through the stress of the dialogue.

The best example is the work I did on Romeo Saganash’s bill on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). That had been a cornerstone of the calls to action of the TRC to get Canadian institutions, including provincial and federal governments, to look at using the UN declaration as a framework to reconciliation.

Being able to explain that to senators, to members of the public and to those who came forward to make submissions on that point — and even those speaking in opposition to the declaration — provided a fine educational opportunity and I think I was able to do that. Now, the government has introduced a government bill to do the same thing. I think it stands to gain more support in the Senate than the original bill did because we did the work to get people to understand what the bill was about, what the declaration was about. Now, that groundwork has all been laid and I think the bill will have a smoother passage through the Senate.

In your maiden speech in the Upper Chamber, you referred to the Senate as Canada’s “council of elders” and said that you accepted the appointment in the hope that you could continue the work of reconciliation through education and understanding. How would you like to see that vision continue?

The Senate should really be looking upon itself as a council of elders for the country and in an image such as that, the vision of a council of elders means that there is no role for partisanship. You have to each speak independently about the future of the country and take the best interests of the country at heart. That includes an approach to reconciliation that is not about protecting interests. It’s a different vision of the Senate that the Senate now holds of itself.

You’re retiring from the Senate with a legacy of advocacy for the natural world. You helped sponsor the bill to end whale and dolphin captivity in Canada, which became law in June 2019, and now you’re attempting to provide the same protection for great apes and elephants. Why is it important to you for Parliament to pass Bill S-218, the Jane Goodall Act?

It’s about setting the tone for the country when it comes to understanding what our relationship is with the other beings of creation. We need to be looking upon other creatures that live with us not only as property and we need to be more respectful of them as true beings. They were put here for a purpose and we need to understand and respect that purpose. The intention was to get people to shift their thinking of the overall approach that we take to animals, that trophy hunting or putting animals on display for entertainment purposes should be condemned. We’re not doing enough in that regard. The purpose of the Jane Goodall Act is to put some parameters around that in recognition of not only that very basic principle, but also in recognition of the role of Jane Goodall.

What advice would you give to the next Indigenous person appointed to the Senate?

To keep in mind that there are many ahead of you now. At the time of this interview, there are 12 Indigenous senators. They all meet regularly about our Indigenous perspective and about things that are happening not only in the Senate, but in the public as well. We call upon members of cabinet to meet with us, to talk to us. We meet with the Indigenous members of the House of Commons to see what kind of collective approach we can take to benefit the Indigenous community. Those senators who are coming after us need to know that there are people who have already shown the way, that there are other Indigenous senators who are already advocating for the kinds of changes that are necessary to achieve reconciliation and that their concerns will not only have support but will be able to continue in the Senate.