Senator Patterson, who helped create Nunavut, retires after a career of northern advocacy

Senator Dennis Patterson, former premier of the Northwest Territories, helped redraw Canada’s map with the creation of Nunavut in 1999.

A Vancouverite who fell in love with the North after moving to Baffin Island as a young lawyer, he joined Inuit political leaders on the two-decades-long campaign to carve out a swath of the Northwest Territories into a distinctly Inuit region.

Ahead of his retirement on December 30, 2023, Senator Patterson sat down with SenCAplus to talk about how his passion for the North carried over to his work in the Senate.

What initially attracted you to the North, and what kept you there for 40 years?

While studying law at Dalhousie University in Halifax, I was privileged to be part of a group that formed a student-run legal aid clinic in the city’s North End. Dalhousie Legal Aid Service continues and is the oldest clinical law program in Canada.

Then a former professor decided I might be a candidate to lead Baffin Island’s legal aid clinic as its first director. I was hired sight unseen, and I left a good job in a southern law firm to take a year’s leave of absence to help start up the clinic. I quickly realized this was a huge challenge, that the community had come to rely on me, and that the work was important.

I was also gobsmacked by the beauty of the Arctic. It changed me in fundamental ways. I fell in love with the land and its beautiful, pristine wilderness.

I found myself participating in hunting expeditions with the Inuit. I was amazed at their thorough utilization of the animals, their respect for wildlife and the spirituality of the experience.

Senator Patterson, far right, as a Northwest Territories MLA at a community meeting in the 1980s with Inuit leaders John Amagoalik, Rhoda Innuksuk, the late Ludy Pudluk, the late Donat Milortuk and Alan Maghagak. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

Senator Patterson, far right, as a Northwest Territories MLA at a community meeting in the 1980s with Inuit leaders John Amagoalik, Rhoda Innuksuk, the late Ludy Pudluk, the late Donat Milortuk and Alan Maghagak. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

A Vancouverite by birth, Senator Patterson moved to Baffin Island when he was a young lawyer. He stayed up North for 40 years, cultivating a love of the land and the Arctic’s “beautiful, pristine wilderness.” (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

A Vancouverite by birth, Senator Patterson moved to Baffin Island when he was a young lawyer. He stayed up North for 40 years, cultivating a love of the land and the Arctic’s “beautiful, pristine wilderness.” (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

Senator Patterson makes a call just before members of the Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples take flight to a remote community during its 2016 northern housing study. Seated behind him are former senators Wilfred Moore, the late Tobias Enverga and Nancy Greene Raine. In the next line of seats, from the front, are former senators Sandra Lovelace Nicholas and Lillian Eva Dyck, along with committee staff.

Senator Patterson makes a call just before members of the Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples take flight to a remote community during its 2016 northern housing study. Seated behind him are former senators Wilfred Moore, the late Tobias Enverga and Nancy Greene Raine. In the next line of seats, from the front, are former senators Sandra Lovelace Nicholas and Lillian Eva Dyck, along with committee staff.

I was a follower and helper to an older, experienced hunter. I was happy to ride on the sled, buy the gas and tag along. One day, he set us up in a place downwind from a herd of caribou. To my astonishment, he handed me a .30-30 rifle when a large bull caribou emerged on the horizon. That was the first rifle shot I had ever fired in my life — I had only seen it done in Western movies — and I shot that magnificent caribou with my first shot. It changed my outlook on life and my attitude towards hunting.

You served for 16 years as an MLA for the Northwest Territories, and then as premier from 1987 to 1991. How did your political career prepare you for the Senate?

We governed by a so-called consensus government system in what is now Nunavut and what was then the Northwest Territories. I worked in committees that were not dominated by a partisan government majority. We worked together collegially.

I felt at home in the Senate because of that less partisan nature, and because of the important work that committees do. I think it’s also an advantage to know Robert’s Rules of Order. I see increasingly there’s less of a premium put on political experience in the appointment of new senators, and there’s some merit to that, but it is also important to have a few folks around who already know the rules and the legislative process.

How has Nunavut evolved in the 24 years since its inception?

I worked with many impressive Inuit leaders and MLAs to establish Nunavut. We envisioned a new homeland for Inuit, one that would preserve and enhance the Inuit language and culture. We wanted Inuit to have the highest degree of self-government of any Indigenous organization in the world. It’s exciting to see Inuit leading the way forward, using their language, enriching their culture and developing the private sector economy, principally through mining.

The territory is still struggling with social issues — including a crisis in housing and an education system that is not yet bilingual and doesn’t produce enough graduates — but Nunavut remains a beacon of hope for Indigenous people throughout the world.

At his cabin on Frobisher Bay, Senator Patterson displays freshly caught Arctic char with his grandson Miles Brewster, son Bruce Uviluq and daughter Jessica Patterson. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

At his cabin on Frobisher Bay, Senator Patterson displays freshly caught Arctic char with his grandson Miles Brewster, son Bruce Uviluq and daughter Jessica Patterson. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

Despite your rich political experience, has anything surprised you about the Senate?

What surprised me was the impact that the Senate can have on the federal government. Early in my Senate career I was appointed deputy chair of the Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans when the federal government tried to “de-staff” remote lighthouses on the east and west coasts. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans wanted to eliminate the lighthouse keepers’ jobs and replace them with automated lights and systems. The committee chair, the late senator Bill Rompkey and I led a very detailed and exciting study on this issue.

We flew in by helicopter to the most remote lighthouses on the east and west coasts, and interviewed lighthouse keepers who had done this job as their fathers, grandfathers and even great-grandfathers had done before them. We went to small towns and met with fishers to learn about the amazing jobs that keepers do in lifesaving, environmental monitoring and maintaining lights in adverse weather. Following our report, within weeks, the government reversed position and announced that the remote lighthouses would remain staffed. It showed me the power and credibility of Senate committees.

I was a member of the Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples, which forced the government to meaningfully eliminate gender discrimination under the Indian Act. There are still some final steps to reverse historical inequities, but it was the Senate that forced that change.

Senator Patterson surveys repairs to a damaged housing unit in Iqaluit during a fact-finding mission on housing in Canada’s North in 2016.

Senator Patterson surveys repairs to a damaged housing unit in Iqaluit during a fact-finding mission on housing in Canada’s North in 2016.

Senator Dennis Patterson is a vocal advocate for the sealing industry in Canada. He’s often seen wearing sealskin products, like this vest, as a show of support for subsistence seal hunters.

Senator Dennis Patterson is a vocal advocate for the sealing industry in Canada. He’s often seen wearing sealskin products, like this vest, as a show of support for subsistence seal hunters.

You are a champion for the seal industry in Canada and you are known to wear seal products in the Senate and around Parliament Hill. Why is it important for you to (literally) wear this cause on your sleeve?

I make a point of wearing seal skin, carrying seal skin briefcases and celebrating Seal Day on the Hill because I understand the hurt, pain and financial losses Inuit have endured because of the opposition to the seal hunt in Europe and throughout the world. It is a great injustice to the subsistence seal hunters of this country.

Senators must have a net worth of $4,000 and own property to be appointed to the Red Chamber. You have been working to eliminate this long-standing requirement — including most recently through Bill S-228, Constitution Act, 2021 (property qualifications of Senators). Why is this important to you?

This requirement for senators, as outlined in our Constitution, is elitist and archaic. It deprives many people of being eligible for Senate appointments.

Three-quarters of Nunavut residents are not eligible to sit in the Red Chamber because they live in social housing. Many First Nations people living on reserves are not eligible to apply to be senators. Anybody who lives in an apartment, rents a trailer and perhaps even owns a condo — because strata title wasn’t considered by the Fathers of Confederation when they designed those provisions — is not eligible to sit in the Senate. While it is important that senators reside in the region they represent, it shouldn’t matter what your dwelling is and whether you are rich.

Former prime minister Stephen Harper, centre, appointed Senator Patterson to the Red Chamber in 2009. Also pictured is Senator Patterson’s wife, Evelyn Ross. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

Former prime minister Stephen Harper, centre, appointed Senator Patterson to the Red Chamber in 2009. Also pictured is Senator Patterson’s wife, Evelyn Ross. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

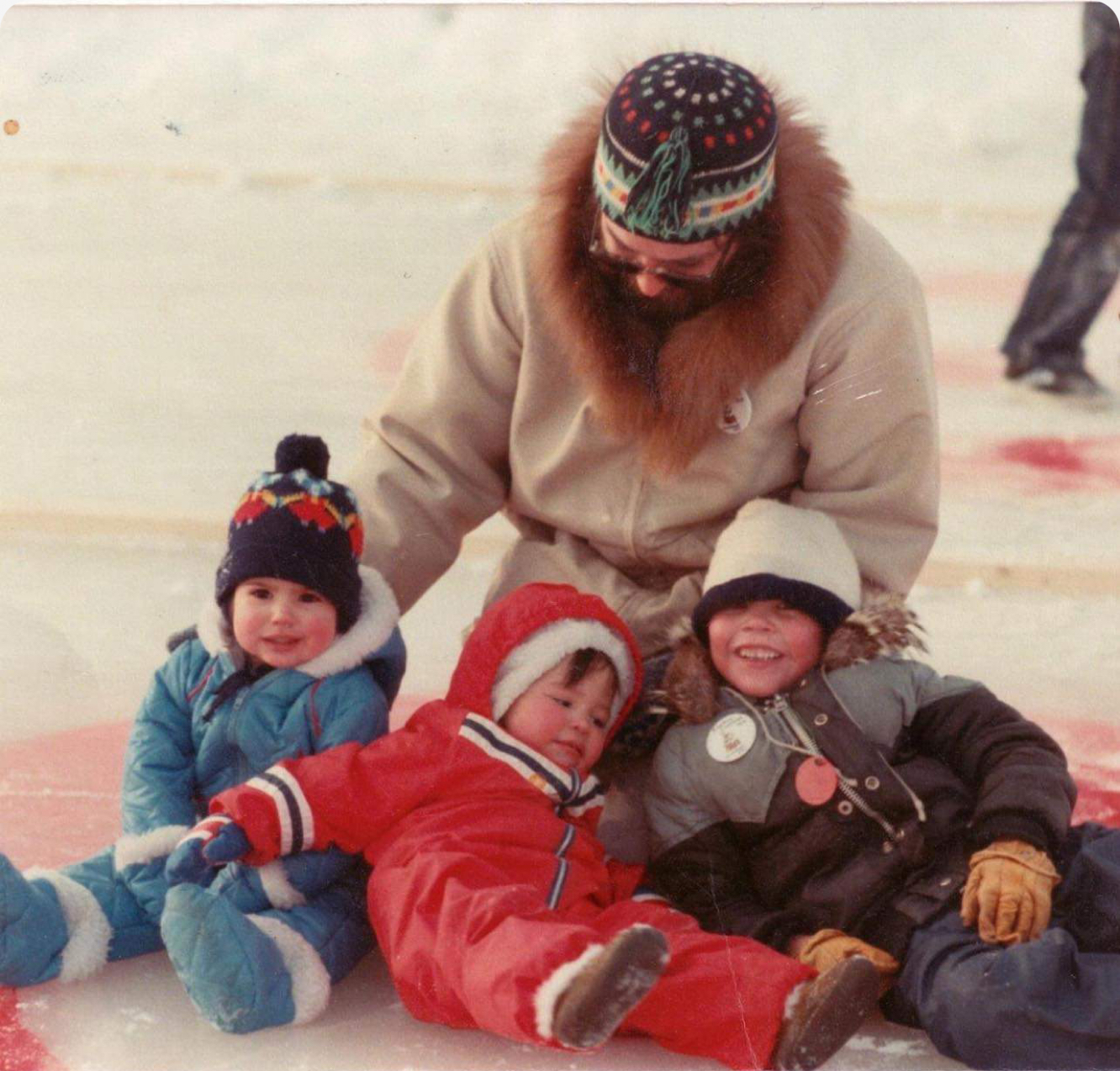

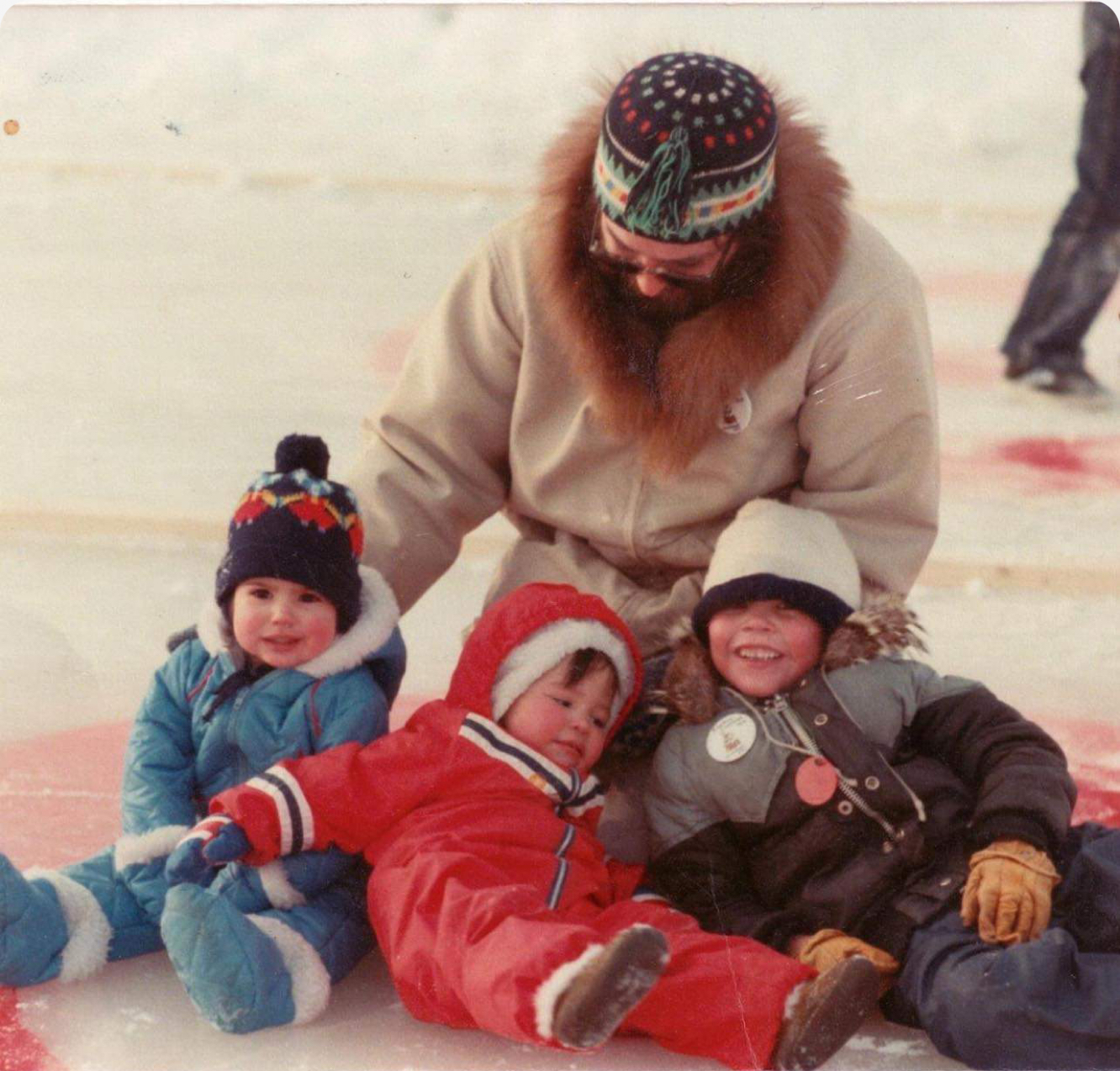

With his children Bruce Uviluq and Jessica Patterson and their friend Oree Wahshee on the ice at Yellowknife’s Caribou Carnival spring festival in 1981. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

With his children Bruce Uviluq and Jessica Patterson and their friend Oree Wahshee on the ice at Yellowknife’s Caribou Carnival spring festival in 1981. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

What is your advice for the next senator to represent Nunavut?

Take advantage of the platform, speak out and be grateful that you’re Nunavut’s only voice in the Senate. Cherish the privilege of having that very strong voice.

You can make a difference. You can move the mountain — even an inch or two.

What do you plan to do in your retirement?

I am going to settle in my home province of B.C. in retirement. I have a son and four grandchildren in the North, as well as lifelong friends, so I’m going to stay connected to them.

I’m also very excited to write about the evolution of Nunavut and tell the stories that I’ve been privileged to experience over the years.

It has been humbling to be a non-Inuk representing Nunavut in the Senate. I had to be dragged kicking and screaming into this office because Nunavut’s population is 85% Inuit and I believe that should be reflected in the territory’s senator. Many of my Inuit friends were surprised at my appointment, but I’ve received great support from Inuit leaders in Nunavut.

Learn more about Senator Patterson in this 2016 interview.

The Honourable Dennis Glen Patterson retired from the Senate of Canada in December 2023. Visit the Library of Parliament's Parlinfo website to learn more about his work in Parliament.

Related articles

Tags

Committee news

Senator Patterson, who helped create Nunavut, retires after a career of northern advocacy

Senator Dennis Patterson, former premier of the Northwest Territories, helped redraw Canada’s map with the creation of Nunavut in 1999.

A Vancouverite who fell in love with the North after moving to Baffin Island as a young lawyer, he joined Inuit political leaders on the two-decades-long campaign to carve out a swath of the Northwest Territories into a distinctly Inuit region.

Ahead of his retirement on December 30, 2023, Senator Patterson sat down with SenCAplus to talk about how his passion for the North carried over to his work in the Senate.

What initially attracted you to the North, and what kept you there for 40 years?

While studying law at Dalhousie University in Halifax, I was privileged to be part of a group that formed a student-run legal aid clinic in the city’s North End. Dalhousie Legal Aid Service continues and is the oldest clinical law program in Canada.

Then a former professor decided I might be a candidate to lead Baffin Island’s legal aid clinic as its first director. I was hired sight unseen, and I left a good job in a southern law firm to take a year’s leave of absence to help start up the clinic. I quickly realized this was a huge challenge, that the community had come to rely on me, and that the work was important.

I was also gobsmacked by the beauty of the Arctic. It changed me in fundamental ways. I fell in love with the land and its beautiful, pristine wilderness.

I found myself participating in hunting expeditions with the Inuit. I was amazed at their thorough utilization of the animals, their respect for wildlife and the spirituality of the experience.

Senator Patterson, far right, as a Northwest Territories MLA at a community meeting in the 1980s with Inuit leaders John Amagoalik, Rhoda Innuksuk, the late Ludy Pudluk, the late Donat Milortuk and Alan Maghagak. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

Senator Patterson, far right, as a Northwest Territories MLA at a community meeting in the 1980s with Inuit leaders John Amagoalik, Rhoda Innuksuk, the late Ludy Pudluk, the late Donat Milortuk and Alan Maghagak. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

A Vancouverite by birth, Senator Patterson moved to Baffin Island when he was a young lawyer. He stayed up North for 40 years, cultivating a love of the land and the Arctic’s “beautiful, pristine wilderness.” (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

A Vancouverite by birth, Senator Patterson moved to Baffin Island when he was a young lawyer. He stayed up North for 40 years, cultivating a love of the land and the Arctic’s “beautiful, pristine wilderness.” (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

Senator Patterson makes a call just before members of the Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples take flight to a remote community during its 2016 northern housing study. Seated behind him are former senators Wilfred Moore, the late Tobias Enverga and Nancy Greene Raine. In the next line of seats, from the front, are former senators Sandra Lovelace Nicholas and Lillian Eva Dyck, along with committee staff.

Senator Patterson makes a call just before members of the Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples take flight to a remote community during its 2016 northern housing study. Seated behind him are former senators Wilfred Moore, the late Tobias Enverga and Nancy Greene Raine. In the next line of seats, from the front, are former senators Sandra Lovelace Nicholas and Lillian Eva Dyck, along with committee staff.

I was a follower and helper to an older, experienced hunter. I was happy to ride on the sled, buy the gas and tag along. One day, he set us up in a place downwind from a herd of caribou. To my astonishment, he handed me a .30-30 rifle when a large bull caribou emerged on the horizon. That was the first rifle shot I had ever fired in my life — I had only seen it done in Western movies — and I shot that magnificent caribou with my first shot. It changed my outlook on life and my attitude towards hunting.

You served for 16 years as an MLA for the Northwest Territories, and then as premier from 1987 to 1991. How did your political career prepare you for the Senate?

We governed by a so-called consensus government system in what is now Nunavut and what was then the Northwest Territories. I worked in committees that were not dominated by a partisan government majority. We worked together collegially.

I felt at home in the Senate because of that less partisan nature, and because of the important work that committees do. I think it’s also an advantage to know Robert’s Rules of Order. I see increasingly there’s less of a premium put on political experience in the appointment of new senators, and there’s some merit to that, but it is also important to have a few folks around who already know the rules and the legislative process.

How has Nunavut evolved in the 24 years since its inception?

I worked with many impressive Inuit leaders and MLAs to establish Nunavut. We envisioned a new homeland for Inuit, one that would preserve and enhance the Inuit language and culture. We wanted Inuit to have the highest degree of self-government of any Indigenous organization in the world. It’s exciting to see Inuit leading the way forward, using their language, enriching their culture and developing the private sector economy, principally through mining.

The territory is still struggling with social issues — including a crisis in housing and an education system that is not yet bilingual and doesn’t produce enough graduates — but Nunavut remains a beacon of hope for Indigenous people throughout the world.

At his cabin on Frobisher Bay, Senator Patterson displays freshly caught Arctic char with his grandson Miles Brewster, son Bruce Uviluq and daughter Jessica Patterson. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

At his cabin on Frobisher Bay, Senator Patterson displays freshly caught Arctic char with his grandson Miles Brewster, son Bruce Uviluq and daughter Jessica Patterson. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

Despite your rich political experience, has anything surprised you about the Senate?

What surprised me was the impact that the Senate can have on the federal government. Early in my Senate career I was appointed deputy chair of the Senate Committee on Fisheries and Oceans when the federal government tried to “de-staff” remote lighthouses on the east and west coasts. The Department of Fisheries and Oceans wanted to eliminate the lighthouse keepers’ jobs and replace them with automated lights and systems. The committee chair, the late senator Bill Rompkey and I led a very detailed and exciting study on this issue.

We flew in by helicopter to the most remote lighthouses on the east and west coasts, and interviewed lighthouse keepers who had done this job as their fathers, grandfathers and even great-grandfathers had done before them. We went to small towns and met with fishers to learn about the amazing jobs that keepers do in lifesaving, environmental monitoring and maintaining lights in adverse weather. Following our report, within weeks, the government reversed position and announced that the remote lighthouses would remain staffed. It showed me the power and credibility of Senate committees.

I was a member of the Senate Committee on Indigenous Peoples, which forced the government to meaningfully eliminate gender discrimination under the Indian Act. There are still some final steps to reverse historical inequities, but it was the Senate that forced that change.

Senator Patterson surveys repairs to a damaged housing unit in Iqaluit during a fact-finding mission on housing in Canada’s North in 2016.

Senator Patterson surveys repairs to a damaged housing unit in Iqaluit during a fact-finding mission on housing in Canada’s North in 2016.

Senator Dennis Patterson is a vocal advocate for the sealing industry in Canada. He’s often seen wearing sealskin products, like this vest, as a show of support for subsistence seal hunters.

Senator Dennis Patterson is a vocal advocate for the sealing industry in Canada. He’s often seen wearing sealskin products, like this vest, as a show of support for subsistence seal hunters.

You are a champion for the seal industry in Canada and you are known to wear seal products in the Senate and around Parliament Hill. Why is it important for you to (literally) wear this cause on your sleeve?

I make a point of wearing seal skin, carrying seal skin briefcases and celebrating Seal Day on the Hill because I understand the hurt, pain and financial losses Inuit have endured because of the opposition to the seal hunt in Europe and throughout the world. It is a great injustice to the subsistence seal hunters of this country.

Senators must have a net worth of $4,000 and own property to be appointed to the Red Chamber. You have been working to eliminate this long-standing requirement — including most recently through Bill S-228, Constitution Act, 2021 (property qualifications of Senators). Why is this important to you?

This requirement for senators, as outlined in our Constitution, is elitist and archaic. It deprives many people of being eligible for Senate appointments.

Three-quarters of Nunavut residents are not eligible to sit in the Red Chamber because they live in social housing. Many First Nations people living on reserves are not eligible to apply to be senators. Anybody who lives in an apartment, rents a trailer and perhaps even owns a condo — because strata title wasn’t considered by the Fathers of Confederation when they designed those provisions — is not eligible to sit in the Senate. While it is important that senators reside in the region they represent, it shouldn’t matter what your dwelling is and whether you are rich.

Former prime minister Stephen Harper, centre, appointed Senator Patterson to the Red Chamber in 2009. Also pictured is Senator Patterson’s wife, Evelyn Ross. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

Former prime minister Stephen Harper, centre, appointed Senator Patterson to the Red Chamber in 2009. Also pictured is Senator Patterson’s wife, Evelyn Ross. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

With his children Bruce Uviluq and Jessica Patterson and their friend Oree Wahshee on the ice at Yellowknife’s Caribou Carnival spring festival in 1981. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

With his children Bruce Uviluq and Jessica Patterson and their friend Oree Wahshee on the ice at Yellowknife’s Caribou Carnival spring festival in 1981. (Photo credit: Office of Senator Dennis Patterson)

What is your advice for the next senator to represent Nunavut?

Take advantage of the platform, speak out and be grateful that you’re Nunavut’s only voice in the Senate. Cherish the privilege of having that very strong voice.

You can make a difference. You can move the mountain — even an inch or two.

What do you plan to do in your retirement?

I am going to settle in my home province of B.C. in retirement. I have a son and four grandchildren in the North, as well as lifelong friends, so I’m going to stay connected to them.

I’m also very excited to write about the evolution of Nunavut and tell the stories that I’ve been privileged to experience over the years.

It has been humbling to be a non-Inuk representing Nunavut in the Senate. I had to be dragged kicking and screaming into this office because Nunavut’s population is 85% Inuit and I believe that should be reflected in the territory’s senator. Many of my Inuit friends were surprised at my appointment, but I’ve received great support from Inuit leaders in Nunavut.

Learn more about Senator Patterson in this 2016 interview.

The Honourable Dennis Glen Patterson retired from the Senate of Canada in December 2023. Visit the Library of Parliament's Parlinfo website to learn more about his work in Parliament.