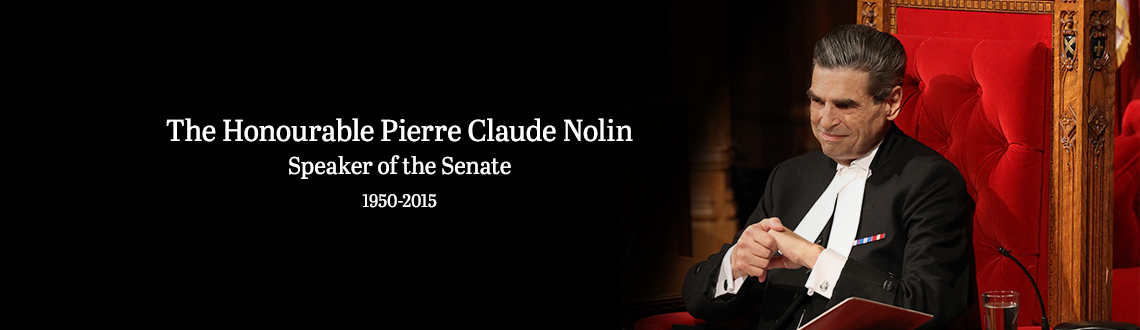

The Honourable Pierre Claude Nolin

43rd Speaker of the Senate (2014–2015)

Speaker's Rulings

February 3, 2015

Bill C-43

I now wish to deal with the point of order raised by Senator Moore on December 12, 2014, with respect to omnibus bills.

While the point of order was raised in relation to Bill C-43, a second Act to implement certain provisions of the budget tabled in Parliament on February 11, 2014 and other measures, Senator Moore challenged omnibus bills more generally. He stated that they:

... contain many issues that are not at all related. It is thus improper to put senators in the position of having to vote once on many unrelated issues. This is fundamentally unfair and out of order.

In outlining his concern Senator Moore addressed Canadian, provincial and international practice, as well as noting some of the literature on the matter. He summarized his position by stating that problems stemming from omnibus bills are ``... getting worse. Somebody must take a stand.''

Several senators supported these views. Senator Fraser distinguished between bills amending a wide range of laws, but clearly linked by a common thread, and those that bring together very disparate matters. She placed Bill C-43 into the latter category, a view shared by Senator Day. Senator Chaput explained, by reference to a concrete case, how omnibus bills may lead to insufficient study of some important parts of a bill, while Senator Ringuette felt that such measures impair the Senate's duty to provide sober second thought. In supporting the point of order, Senator Eggleton then noted that he actually supported some parts of Bill C-43, but, because of its broad scope, it does not allow parliamentarians to express themselves properly.

Other senators challenged these arguments. Senator Martin referred to practices in the other place when explaining that omnibus bills are an accepted part of Canadian parliamentary practice. Senator Smith (Saurel) and Senator Lang outlined how they think Bill C-43 does have a common thread — implementing a wide-ranging budget plan to deal with a challenging international economic situation and promote prosperity for Canadians. The Leader of the Government, Senator Carignan, expressed understanding for the concerns raised by Senator Moore, but underscored that the Senate can adapt its procedures as it wishes in order to deal with such problems. This house has, for example, adjusted the pre-study process provided for in the Rules in a way that allows input from a range of committees. This may help deal with some of the concerns noted.

During the consideration of the point of order a consensus developed that the Senate's study of Bill C-43 should not be delayed. Proceedings on the bill could thus continue, and it received Royal Assent the next week. While Bill C-43 is therefore no longer an issue, the broader issue about omnibus bills remains. It is, as you know, not new. Several honourable senators have objected to large and complex bills at various times over the years, so a review of the topic is timely.

Despite the concerns about omnibus bills, there has actually been only one point of order on the issue in the Senate since 1984. In a ruling given on October 23, 2003, the Speaker stated that he was ``... unaware of any requirement that [an omnibus] bill must possess a common theme ...''.

The situation is quite different in the other place, where the Speaker has addressed about the question of omnibus bills on a number of occasions. As indicated in the second edition of House of Commons Procedure and Practice, at p. 725, ``It appears to be entirely proper, in procedural terms, for a bill to amend, repeal or enact more than one Act, provided that the requisite notice is given, that it is accompanied by a royal recommendation (where necessary), and that it follows the form required.'' The Speaker of the Commons has sometimes been asked to divide a bill, but has declined to do so without guidance and authority from the house. As stated on June 8, 1988, ``Until the House adopts specific rules relating to omnibus Bills, the Chair's role is very limited and the Speaker should remain on the sidelines as debate proceeds and the House resolves the issue.''

When an omnibus bill comes to the Senate from the House of Commons, we must be mindful of the fact that we are dealing with a bill already adopted by one of the component parts of Parliament. We ought not to question how or why the other place adopted the measure, but should fulfil our legislative work by conducting our own careful and independent — or autonomous — review in the way that best meets our needs. There may be situations where procedural issues can arise in relation to a bill from the Commons — I think, for example, of the occasional cases where it is found that Royal Consent is required for a bill — but they are infrequent.

In his point of order Senator Moore said that ``Somebody must take a stand'' with regards to omnibus bills. To the extent senators agree that there is a problem with this type of bill, this statement may have merit. It is not, however, for the Speaker, acting unilaterally, to decide what stand to take, or when to take it. The Speaker deals with procedural issues, in light of our Rules and practices. The Senate's Rules are silent about omnibus bills, and our practices allow for them. From this perspective, such measures are a part of how the Canadian Parliament operates. In addition, we must not lose sight of the fact that, at least in procedural terms, the question put on an omnibus bill — not the content of the bill, but the actual question — is quite simple. It is whether the bill will be read a second or third time. Bills are thus quite different from complex questions, where the Speaker may, in very rare situations, exercise some discretion by dividing a motion.

Honourable senators, it may be helpful at this point to reflect briefly upon some more general issues that are relevant to omnibus bills. As the Supreme Court stated in the 2014 decision on the Reference re Senate Reform, the Senate is ``... one of Canada's foundational political institutions. It lies at the heart of the agreement that gave birth to the Canadian federation.'' As members of this house we have various duties and responsibilities, including representing our regions, legislative work, holding government to account, international work through parliamentary diplomacy, the protection of minorities, and the study and support of public policy issues. We bring our divergent backgrounds and experiences to the national Parliament as we perform these roles.

Drawing on the wealth of experience among its members, the Senate is well placed to act as a complementary chamber within Parliament. The idea of complementarity does not imply that one house is inferior to the other. Instead, the Senate and the House of Commons play different roles and interact with each other in a way that may sometimes, it is true, result in a level of tension. But this leads to an effective system of government that is greater than the sum of its parts. This interaction has been a key part of the country's constitutional architecture since its founding. Working together the houses enrich and strengthen our national Parliament. The Senate provides a different perspective from the House of Commons, even when studying similar questions, and focuses on different issues. This house can therefore provide a careful and autonomous second review of measures adopted by the elected house. Our generally less intensely partisan atmosphere, and the good working relationships we develop amongst ourselves, regardless of political affiliation, greatly assist us in performing these responsibilities.

I say this, honourable senators, because nothing should prevent us from reconsidering how we deal with omnibus bills, or any aspect of our business, if we feel that changes could help us better perform our role as parliamentarians. We must ensure that we continue to fulfil the expectations of Canadians as well as the role this house was given by those who developed our basic structures of government.

A central issue underlying Senator Moore's point of order is the way in which the Senate deals with budgetary measures and bills with financial implications. In this regard, I would remind honourable senators that almost one hundred years ago a special committee studied the rights of the Senate with respect to financial legislation. Its report — generally called the Ross Report — was tabled on May 15, 1918, and adopted on May 22. It may be timely to review this topic, so that honourable senators can consider how, in the modern context, this house can best use its powers to fulfil its duties. In any such review, attention would also have to be given to the principle, enunciated by Sir John A. Macdonald, that the Senate ``... will never set itself in opposition against the deliberate and understood wishes of the people.'' The proper bounds for this self-imposed limitation certainly merit reflection.

As a related point, the Senate — perhaps through one of its committees — may wish to review the way in which it could better ensure government accountability, particularly in relation to public finances and expenditures. Our practices allow the National Finance Committee to develop a strong understanding of the Estimates and the workings of government. The value of this broad oversight role has been recognized by observers, but it may be desirable to ensure that other committees develop a similar capacity. Without affecting the role of the National Finance Committee, the Senate could consider having other committees also study specific parts of the Estimates relevant to their subjects. An understanding of how other jurisdictions — both within Canada and abroad — deal with such matters would assist any evaluation of how this institution could adjust its operations.

To focus more specifically on the issue of omnibus bills, it is also possible to identify various ways in which the Senate could change its procedures, if there is a wish to do so. Here again, information on procedures for dealing with such bills in other jurisdictions would be helpful. In Saskatchewan, for example, the Rules specifically circumscribe the situations in which omnibus bills can be introduced. Only those dealing with a single broad policy or making similar amendments to existing acts are allowed.

In the Senate a practice has developed to use pre-study for budget implementation bills, and to allow different committees to provide input in relation to those parts that are relevant to their fields of expertise. A first simple change might be to include this process in the Rules, so that it becomes the norm for all omnibus bills.

Going one step further, a second option would be to make the process automatic for large or complex bills, rather than optional. With such a change, the National Finance Committee would be able to study the subject matter of budget implementation bills in collaboration with other committees, but without waiting for an order of reference from the Senate.

A third option, and a variation on this idea, would be to develop a way for different parts of an omnibus bill to be referred to different committees after second reading. This would allow the committees to study the elements of the bill relevant to their fields in detail and to actually propose their own amendments.

Even without such changes, senators have powerful tools available. Most dramatically, the Senate can defeat a bill, even one proposed by a minister, without bringing about the fall of the government. We have even done so with a budget implementation bill in the past. Senators also have the option, which they regularly exercise, of proposing amendments to bills in committee and at third reading.

The rarely-used possibility of dividing a bill is another tool available to the Senate, if there is a concern that a bill is too large or complex. Within our current practices, a committee cannot propose dividing a bill without special authority from the Senate. The Rules could, however, be amended to give a committee dealing with an omnibus bill the power to propose division on its own initiative, if it decides either that this could assist the Senate's study of the bill or that there is no common theme between the different parts of the bill. Such a course of action should, of course, only be taken after the sponsor has had ample opportunity to provide reasons against dividing the bill or to explain the common theme linking its different parts together.

These are only some ideas. There are no doubt other ways that we can deal with any concerns that may exist in relation to omnibus bills. However, within the current framework of the Rules of the Senate and practices such bills are acceptable and can proceed through the Senate in the same way as any other bill. Nothing should prevent the Senate, perhaps after study by the Rules Committee, from reconsidering how it deals with omnibus bills if it so wishes. Any changes are, however, for the chamber itself to decide, and not for the Speaker to impose.