A Supreme Sesquicentennial: The Upper Chamber’s high court connections

The Supreme Court of Canada turned 150 in April 2025. And when the 45th Parliament opens with the Speech from the Throne, the nine Supreme Court justices will return to the chamber where it all began.

Although the Supreme Court didn’t exist at Confederation, Canada’s founding constitutional document, the British North America Act — later renamed the Constitution Act, 1867 — included a provision for its establishment.

There was a strong case for such a court by 1875. Administration of the growing country had become increasingly complex. There was pressure to consolidate decision making closer to home and to establish an authority that could interpret the constitution and provide legal clarity on issues affecting the country’s evolution.

Senator Luc Letellier de St-Just, Leader of the Government in the Senate, argued that such a court “would offer more security to us, afford greater facilities for the settlement of appeals and prove far less expensive to suitors.”

It was a matter of Canadian sovereignty, added Senator Alexander Campbell, one of the Fathers of Confederation: “We all feel the desire — inherent, I suppose, in young nations — to stand upon our own strength and to endeavour to accumulate upon ourselves all the attributes of nationality.”

Still, there was hesitation. Some politicians feared that the new court might erode provincial rights by repeatedly ruling in the federal government’s favour.

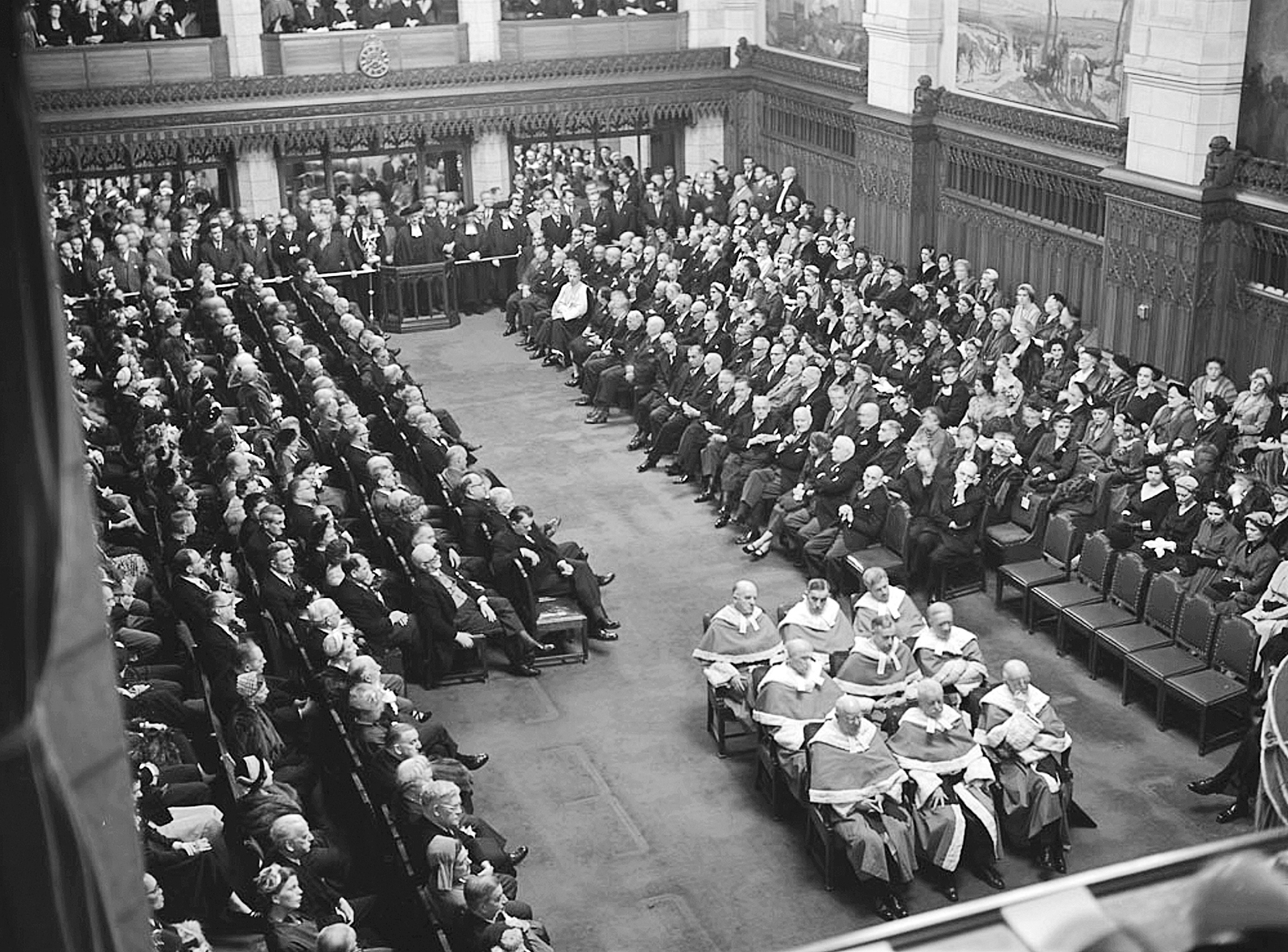

Nevertheless, on April 8, 1875, Parliament passed a law establishing a permanent national court in Ottawa, comprising six judges. The Chief Justice administered the oaths of allegiance and of office to the other five justices in the Senate Chamber in the autumn.

The Senate was also the court’s first customer. In April 1876, the Senate sent a reference to the court, asking whether a particular bill — An Act to incorporate the Brothers of the Christian Schools in Canada — fell under federal or provincial jurisdiction. The court, in its first interpretation of the country’s constitution, ruled it was a provincial matter.

The Supreme Court was not initially the country’s highest court — its decisions could be appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the United Kingdom. That played an important part in Senate history when, in the 1920s, a group of Canadian women’s rights advocates — known today as the Famous Five — launched a bold legal challenge.

They asked for clarification of a line in the British North America Act that said only “qualified Persons” could serve in the Senate. They petitioned the Canadian government to ask the Supreme Court whether that included women.

Well worth the paper it’s printed on

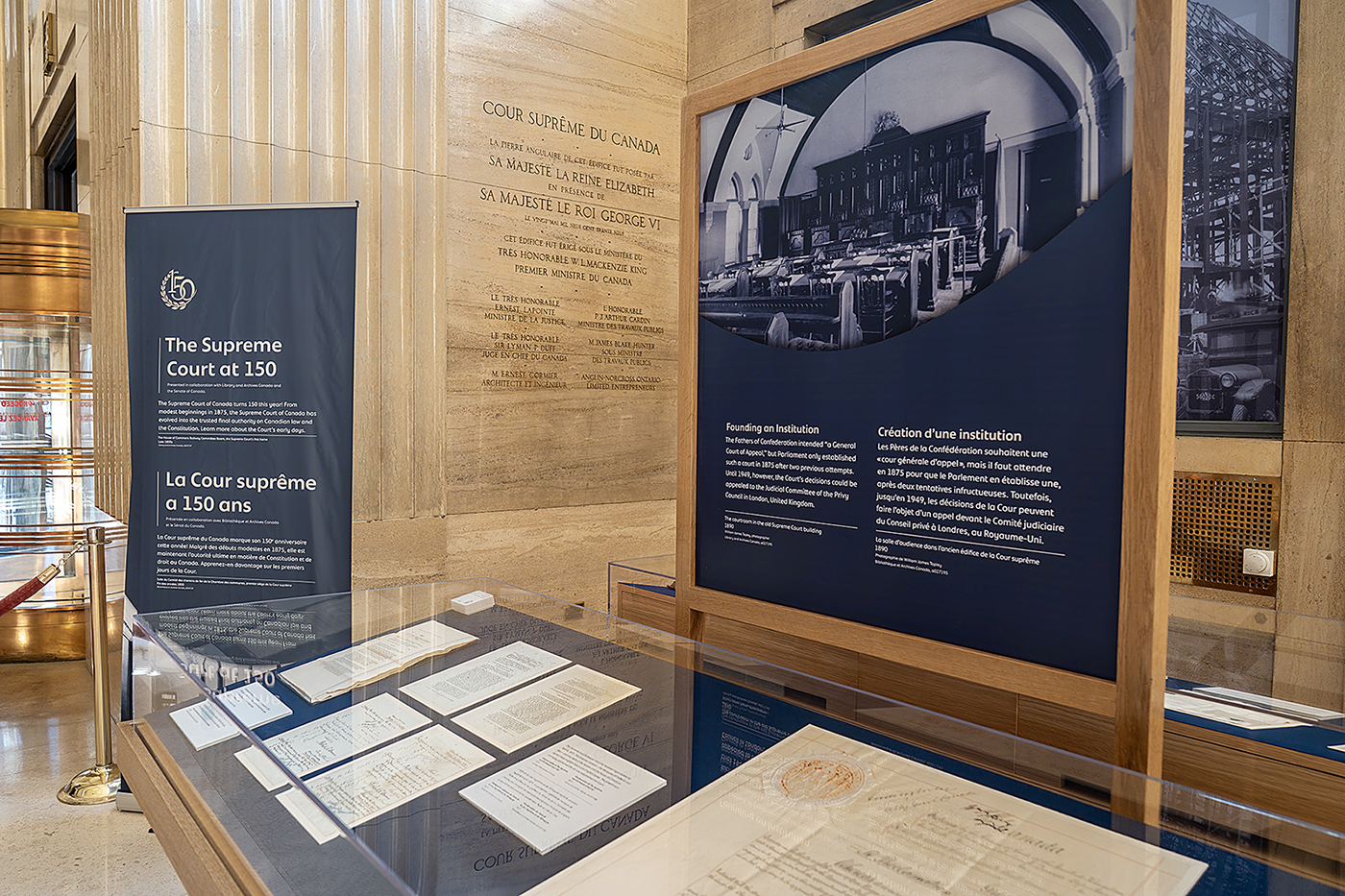

To celebrate the Supreme Court’s 150th anniversary, the Senate is sharing the original act of Parliament that brought the court into existence in 1875 — and the public will be able to see it.

The title and signature page of An Act to establish a Supreme Court, and a Court of Exchequer, for the Dominion of Canada will be on display at the Supreme Court building as of April 2025 thanks to a loan agreement between the Senate and the court.

The act is in the Senate’s care because of the Publication of Statutes Act, which grants custody of all original statutes passed by Parliament — before and after Confederation — to the Clerk of the Senate and the Clerk of the Parliaments. The oldest piece of legislation preserved in the Senate’s vaults is a handwritten 1849 parchment from the Province of Canada.

The display is a team effort.

Professionals from the Canadian Conservation Institute were brought in to examine the act and help determine how it can be safely displayed without getting damaged. Humidity, temperature and even light exposure can affect the condition of the document.

Experts from Library and Archives Canada then mounted the four original pages on matboards using strips of Japanese paper — a conservation-appropriate adhesive — to prevent bending.

The Library of Parliament also contributed a special portfolio so the documents can be transported without damage.

The exhibit will run until October 10, 2025. The original pages will be replaced with reproductions on May 27, 2025; the originals will be redisplayed between October 2 and 10, 2025.

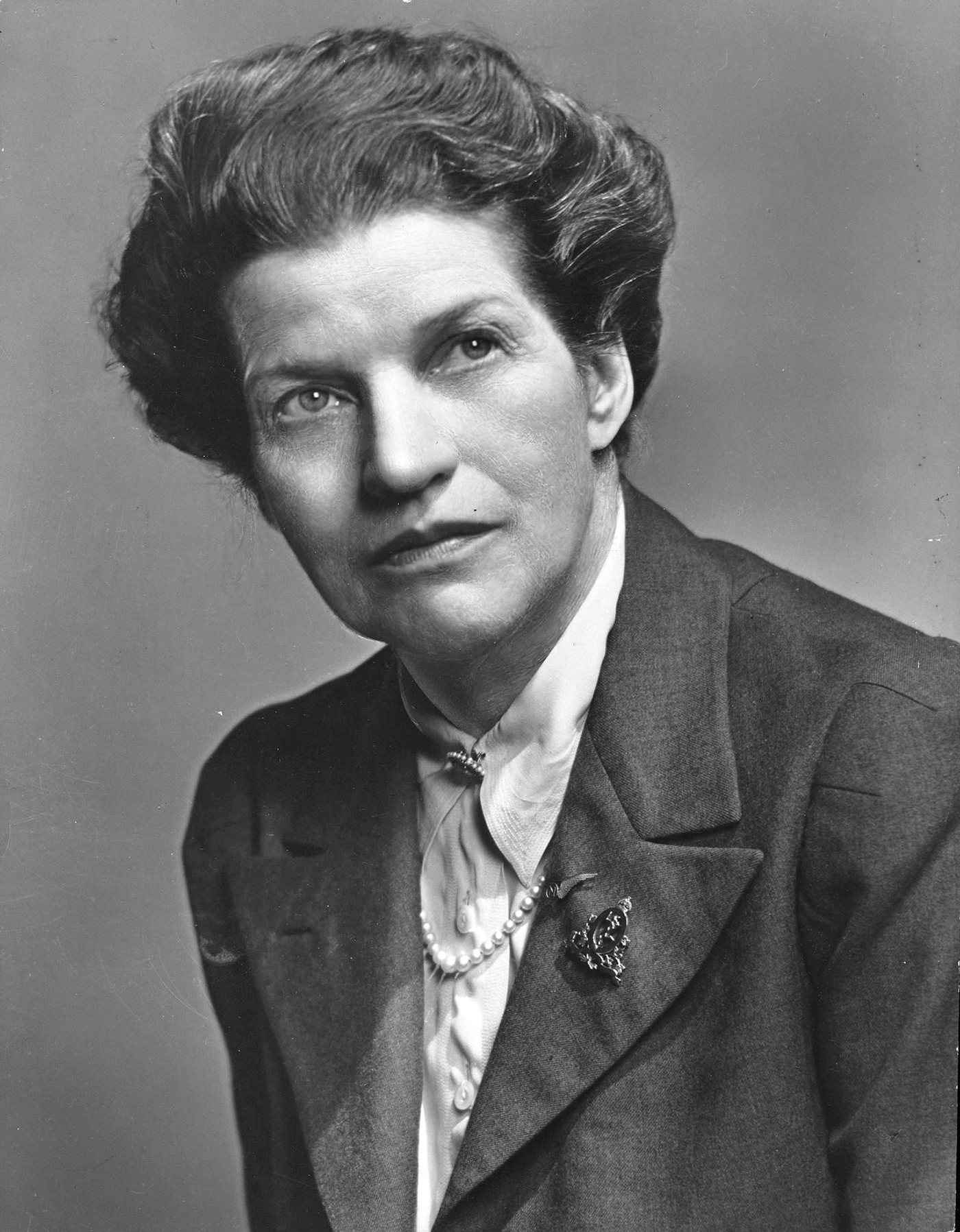

In April 1928, the all-male court ruled that no, “qualified Persons” did not include women. Defiant, the Famous Five appealed to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. A year and a half later, the British court overturned the decision.

As a result, women were welcomed into the Senate. In short order, Cairine Wilson, an advocate for underprivileged children, refugees and the poor, was appointed in 1930. In her inaugural speech in the Upper Chamber, Senator Wilson praised the tenacity of the Famous Five.

“I cannot forget the valiant part that has been taken by those women who have carried our case even to His Majesty’s Privy Council,” she said.

“Canadian women owe a debt of gratitude for their success to those determined women.”

In 1949, the right to appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ended. The Supreme Court has been Canada’s highest court ever since. Its original roster of six judges has grown to nine, appointed by the governor general acting on the advice of the prime minister and cabinet.

An enduring connection between the Senate and the Supreme Court is on display during the Speech from the Throne that opens Parliament with a summary of the government’s intentions for the legislative session. During the ceremony, the nine Supreme Court justices sit front and centre in the Senate Chamber, directly facing the Thrones of Canada. Since 1953 they’ve had comfortable seats — before that, they had to squeeze together on the lumpy and uncomfortable woolsack.

On rare occasions, someone other than the governor general, the monarch’s representative in Canada, delivers the speech. Queen Elizabeth II read it during her 1957 and 1977 royal tours, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court has done so four times — in 1931, 1940, 1963 and 1974.

Why is this? The Chief Justice is third in Canada’s Order of Precedence, behind the governor general and the prime minister, and just ahead of the Senate Speaker. This means the Chief Justice can step in to perform viceregal duties if the governor general is unavailable. When acting in this capacity, the Chief Justice is known as the Administrator of the Government of Canada.

For Senator Pierre J. Dalphond — a former Supreme Court clerk and judge at the Court of Appeal for Quebec — the Supreme Court remains a point of national pride.

“Since its creation, the Supreme Court has evolved from an intermediate court of appeal to the highest court in a country with a federal constitution and a Charter of Rights,” he said.

“On a case-by-case basis, a dialogue has developed between it and Parliament, marked by its neutrality and its respect for the separation of powers intended by the Constituents. Its judgments are widely accepted here and even cited elsewhere in the world.

“It’s an institution Canadians can be proud of.”

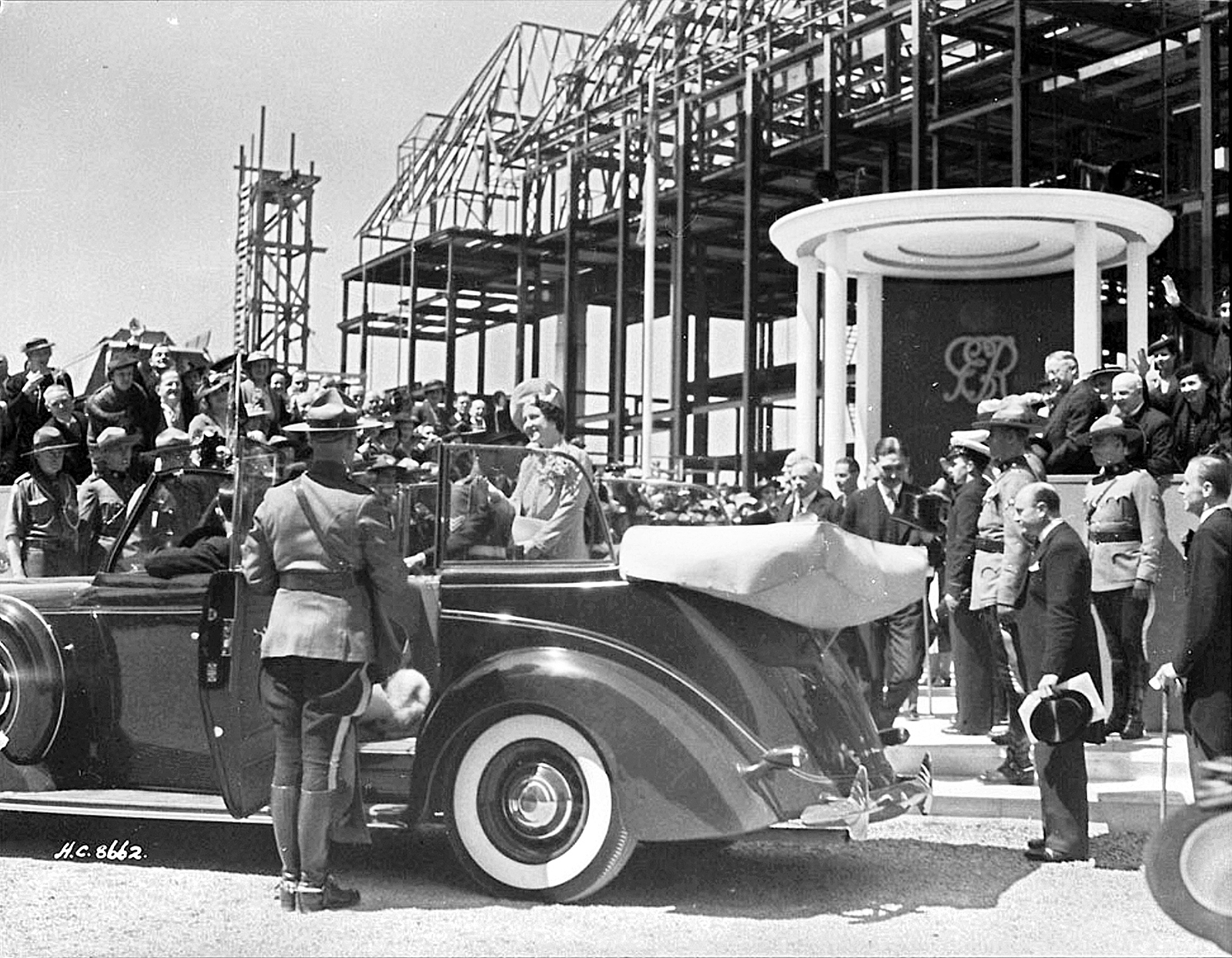

King George VI’s consort, Queen Elizabeth — later known as the Queen Mother — arrives to lay the cornerstone as construction begins on the Supreme Court building in 1939. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

King George VI’s consort, Queen Elizabeth — later known as the Queen Mother — arrives to lay the cornerstone as construction begins on the Supreme Court building in 1939. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Ottawa’s Women are Persons! monument stands beside the Senate of Canada Building. The Famous Five — Emily Murphy, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Nellie McClung, Louise McKinney and Irene Parlby — are depicted here celebrating their victory in the Persons Case, when they successfully appealed a Supreme Court ruling and opened the Senate to women.

Ottawa’s Women are Persons! monument stands beside the Senate of Canada Building. The Famous Five — Emily Murphy, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Nellie McClung, Louise McKinney and Irene Parlby — are depicted here celebrating their victory in the Persons Case, when they successfully appealed a Supreme Court ruling and opened the Senate to women.

Ernest Cormier was the architect responsible for the Supreme Court of Canada building. He designed several prominent Art Deco buildings in Montréal in the 1920s and 1930s. (Photo credit: Getty Images)

Ernest Cormier was the architect responsible for the Supreme Court of Canada building. He designed several prominent Art Deco buildings in Montréal in the 1920s and 1930s. (Photo credit: Getty Images)