Architecture of the Senate: Parliament and Crown meet in the Senate foyer

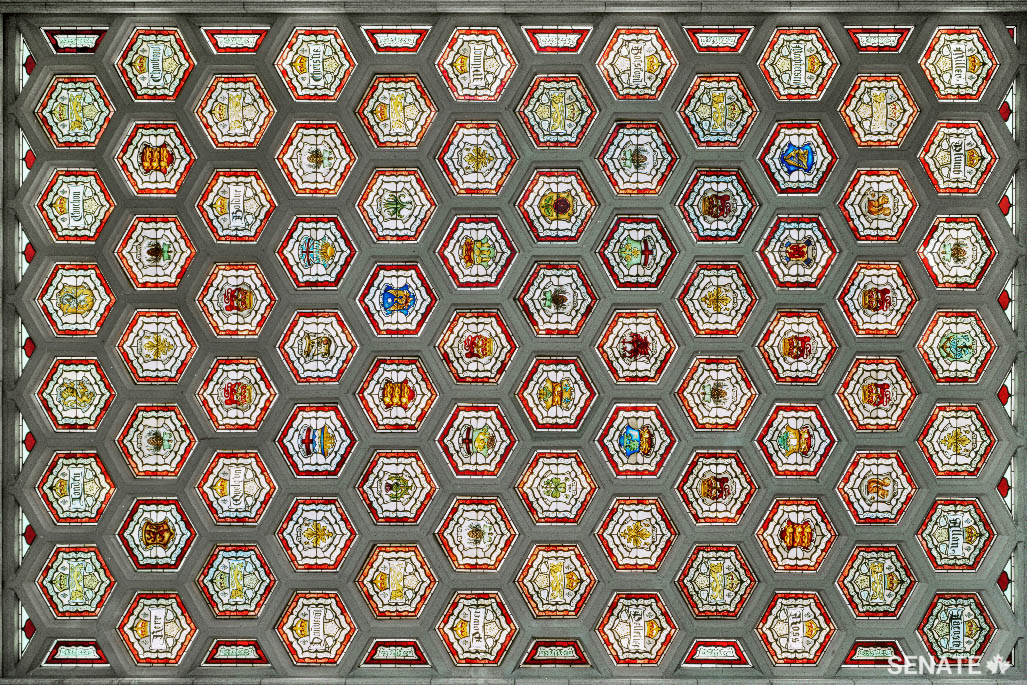

Anyone visiting the chamber where the upper house of Canada’s Parliament sits will pass through the Senate foyer. The ceremonial entrance to the Red Chamber — with its pointed arches, soaring columns and stained-glass windows — is spectacular but often overlooked. This is a shame since the hall is a masterpiece of early 20th-century architecture and a treasure trove of painting and sculpture.

As grand as the portico of any cathedral, the structure is less than a century old. It was erected when Centre Block was rebuilt after a 1916 fire razed the original 19th-century building. Although reconstruction was largely complete by 1927, carving in the foyer was not undertaken until the late 1950s.

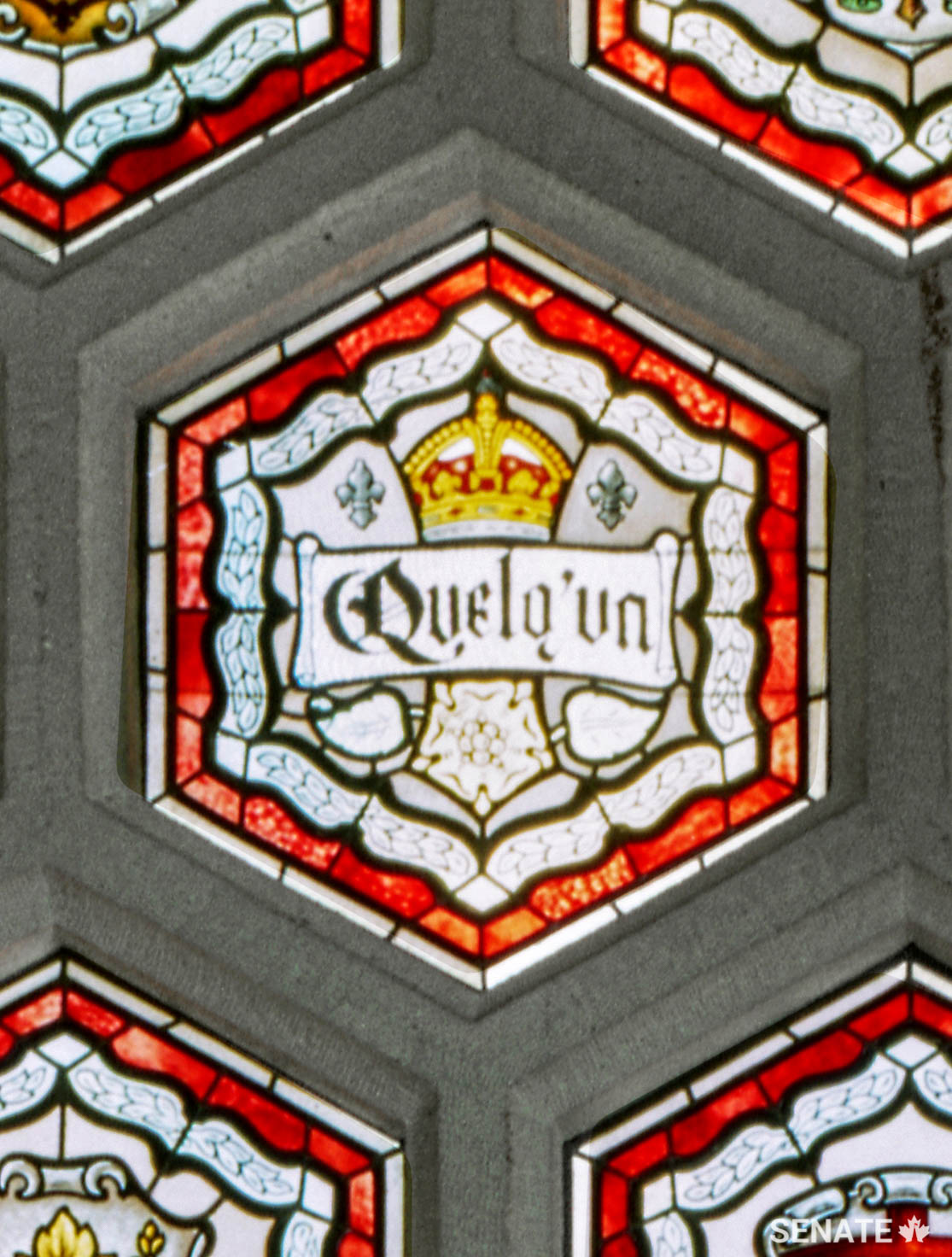

Like the rest of Centre Block, the Senate foyer was built in the Gothic Revival style, a style indelibly associated with an English parliamentary tradition dating to the 13th century. Symbolically, the foyer highlights the partnership between Parliament and Crown, since the Senate is where the sovereign or her representative, the governor general, addresses the combined members of both houses at the beginning of each session of Parliament.

Six carved portraits of Canada’s sovereigns since Confederation— from Queen Victoria to Queen Elizabeth II — adorn the columns immediately in front of the Senate chamber entrance. Elizabeth’s was unveiled in 2010.

The oldest work of art in the foyer is the portrait of George III (1738-1820) painted by Joshua Reynolds, the most sought-after portraitist in Britain in the late 1700s. Nearby hangs Robert Swain’s portrait of King George VI. It depicts a quietly dignified king who overcame a debilitating stutter to rally his nation during the Second World War. This personal struggle was dramatized in the Oscar-winning movie, The King’s Speech.

The core of this collection of royals is the full-length state portrait of Queen Victoria, the Queen of Canada at the time of Confederation. It was saved from the 1916 fire by being sliced out of its frame and hurriedly bundled out of the building.

The sculpted relief near the ceiling of the Senate foyer contains French and English royal symbols, representations of Huron and Iroquois first peoples, a Viking and significant figures from Canada’s history. Look just below the frieze; six mysterious heads gaze solemnly across the colonnade. Two of them are traditional helmeted knights but four are the sculptors themselves, who took the liberty of an unsupervised overnight shift to immortalize themselves in stone.

Explore the foyer — and the rest of the Senate — in detail by taking the Senate Virtual Tour.