Conservators uncover hidden details while bringing a collection of Senate portraits back to life

In February 2019, the Senate moved to the Senate of Canada Building, a former train station built in 1912. The Senate will occupy this temporary location while Parliament’s Centre Block — the Senate’s permanent home — is rehabilitated.

Although Centre Block is shuttered for rehabilitation work, Canadians can still experience its art and architecture through the Senate’s immersive virtual tour.

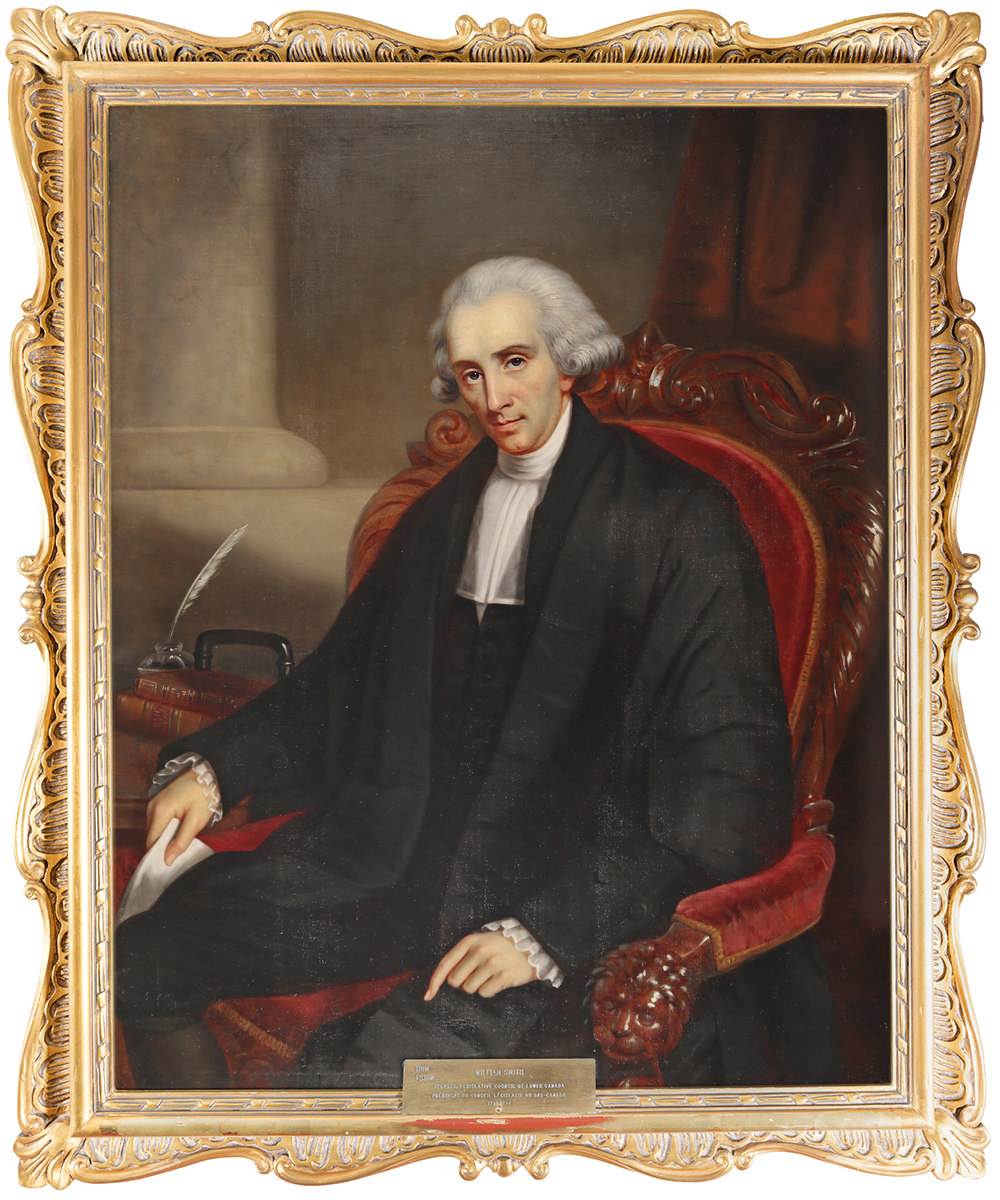

A little worn around the edges after being on display for a century and a half, five Senate treasures have gotten some well-earned TLC.

They’ve survived fires, amateur restorations and the ravages of time. Several are older than the country itself. Three are not even originals; those were destroyed in 1849 when a mob torched Montreal’s St. Anne’s Market, temporary home to the Parliament of the United Province of Canada.

Now, these five portraits depicting Speakers of the Senate — or, in most cases, its predecessors, the legislative councils of pre-Confederation Canada — have been restored to their former glory.

These portraits are reminders of Canada’s time as a British colony and later as a union of French and English-speaking provinces racked by political unrest, with a capital that drifted between five different cities.

It wasn’t until 1867 that Confederation brought political stability and the original Centre Block provided a secure home for Parliament in Ottawa.

The current Centre Block is where these portraits, part of the Senate’s Artwork and Heritage Collection, hung until work got underway to rehabilitate the building. After they were removed from Centre Block, the Senate contracted Ottawa’s Legris Conservation to restore the paintings in the winter of 2021.

The Ottawa workshop tackled the portraits over eight weeks, taking roughly three weeks to complete each. Every component went under the magnifying glass: varnish, paint, frames. Even the canvases and wooden supports that stretch them taut needed urgent attention.

“The edges of the canvases, where they fold over the stretcher, had become so weak they’d torn in many areas,” said conservator David Legris. “We had to remove and reline them, then remount them on their original stretchers.”

It was not the ravages of time or rough handling that presented the most difficult challenge. It was undoing damage inflicted by clumsy restoration attempts in the early 1900s. For instance, background details were often heavily overpainted to mask cracks and abrasions.

“There were very few professional conservators in those days,” Mr. Legris explained. “They usually had artists come in to repaint areas. A lot of the old restorations were pretty heavy-handed.”

The Legris team then began the delicate task of touching up bare spots. Chipped paint, cracks and abrasions were patched with water-based, reversible acrylic pigments.

With the thick layers of overpaint removed, the original brushwork re-emerged and the genius of the artists who created the portraits became more apparent than ever.

Three of these portraits were painted by Théophile Hamel, one of Canada’s most successful artists in the 1800s. He painted the upper echelons of Quebec society — politicians, doctors, merchants, bankers, priests and bishops. His success earned him a substantial income and allowed him to join Quebec’s intellectual and social elite.

Parliament was a particularly good client and the disaster of 1849 delivered a windfall for Hamel. In 1853, he was commissioned to paint nearly 20 portraits to replace ones that had been destroyed in the attack on Parliament four years earlier. Hamel’s versions were not mere copies; they were completely new depictions that required him to track down the original sitter or, if they had died, comb archives and newspapers for reference images.

The other positive attribution experts can make here is to Théophile Hamel’s nephew, Eugène, the artist behind the likeness of Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau, the fourth Speaker of the Senate.

Eugène had apprenticed in his uncle’s studio then set off for Europe to paint its landscapes, tour its galleries and study at its prestigious academies. He honed his craft in Antwerp, Belgium and Rome, Italy, building a reputation as one of North America’s most promising portraitists, before returning to Quebec to take over his uncle’s studio after Théophile’s death in 1870.

“These old academically-trained artists were total masters of their craft,” said Mr. Legris. “For conservators, it’s a joy to work on pieces like these. We always know what we’re dealing with and we know how the paintings are going to react because the artists were so meticulous.”

Restored to their original glory, the five paintings have returned to a climate-and-temperature-controlled storage facility, awaiting their eventual return to Centre Block where Canadians will be able to see them almost exactly as the artists intended.