How the Senate’s new home transformed turn-of-the-century Ottawa

This article is part of a series about the Senate of Canada’s move to the Senate of Canada Building, formerly known as the Government Conference Centre. In 2018, the Senate began to move into the building, a former train station built in 1912, while Parliament’s Centre Block — the Senate’s permanent home — is rehabilitated. The Senate will begin operating from the Senate of Canada Building in early 2019.

The savings to taxpayers will be approximately $200 million compared to the original proposal to find an alternative location on Parliament Hill. The Senate is expected to occupy its temporary location for at least 10 years.

The Government Conference Centre, the modern-day temple on the Rideau Canal that will soon become temporary home to Canada’s Senate, is a cherished Ottawa landmark.

When the city’s central train station opened in June 1912, however, it was greeted with a mixture of bewilderment and amusement. What to make of this $1.9-million granite colossus? And what to make of the fairytale-like Chateau Laurier facing it, unveiled at the same time? A Roman temple paired with a French chateau; some wondered if it was a joke. Others could appreciate the grander plan at work.

Constructed by the Grand Trunk Railway, a Montreal-based company that built much of Canada’s rail infrastructure, the station and hotel were designed as an ensemble. The company gambled that investing in monumental architecture would transform workaday Ottawa into a glamour destination. Its rival, Canadian Pacific Railway, had already built a string of such hotels — Quebec City’s Chateau Frontenac (1893), the Banff Springs Hotel (1888) and Victoria’s Empress Hotel (1908) — and was reaping the rewards of an exploding tourism industry.

The gamble paid off. Grand Trunk Central Station, rechristened Union Station in 1920, became Ottawa’s transport and social hub. For half a century, almost everyone who visited the city — celebrities, world leaders and royalty — passed through it. But transportation was not the only thing at stake. This was about transforming Ottawa into a capital city in more than name alone.

The country was booming. From 1896 to 1914, Canada had the world’s fastest-growing economy, built on a wave of immigration, industrial growth and expansion west.

Many, including then-Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier, felt its status was not reflected in its capital city. Beyond the trio of Gothic-revival edifices that crowned Parliament Hill, Ottawa remained the ramshackle logging town it had been 50 years earlier when Queen Victoria designated it the seat of Parliament. Factories and residential neighbourhoods crowded together. Rail lines ran helter-skelter. Smokestacks blocked views of Parliament Hill. It was hardly a capital worthy of what Laurier had dubbed “Canada’s century.”

Ottawa looked to bold architecture to broadcast its new status. The architectural movement that embodied this early twentieth-century bravado was the Beaux Arts. With its grand staircases, barrel-vaulted ceilings, cavernous rotundas and Corinthian columns, no building exemplified this aesthetic better than Ottawa’s Union Station.

“The building has been through a lot of changes in the century since, not all of them beneficial,” says Senator Scott Tannas, Chair of the Senate Subcommittee on the Long Term Vision and Plan, which is overseeing the Senate’s relocation. “The current renovation is an opportunity to restore the building to its original elegance and the Senate is serving as a catalyst for that.”

Grand architecture demanded an equally grand setting. An overarching civic plan tied Grand Trunk’s transport complex to the government complex 400 metres to the west via Connaught Place, a sweeping triangle of green lawns and wide boulevards.

Five prominent buildings, now gone, ringed the plaza: the old post office, the Russell House Hotel — the city’s finest until the Chateau Laurier was built — the Russell Theatre, old City Hall where the National Arts Centre now stands and, beside it, Knox Presbyterian Church.

By 1939, all would be gone, destroyed by fire or demolished to make way for the new National War Memorial. The 21-metre granite arch, originally designed to commemorate Canadians who fought and died in the First World War, forms the ceremonial heart of today’s Confederation Square.

Banner photo: Library and Archives Canada

Grand Trunk Central Station is seen from the entrance to the Chateau Laurier in 1916, four years after their joint opening. (Library and Archives Canada)

Grand Trunk Central Station is seen from the entrance to the Chateau Laurier in 1916, four years after their joint opening. (Library and Archives Canada)

Connaught Place and Ottawa’s old post office appear in this 1926 photograph, with the Chateau Laurier and Union Station across the Rideau Canal. (Library and Archives Canada)

Connaught Place and Ottawa’s old post office appear in this 1926 photograph, with the Chateau Laurier and Union Station across the Rideau Canal. (Library and Archives Canada)

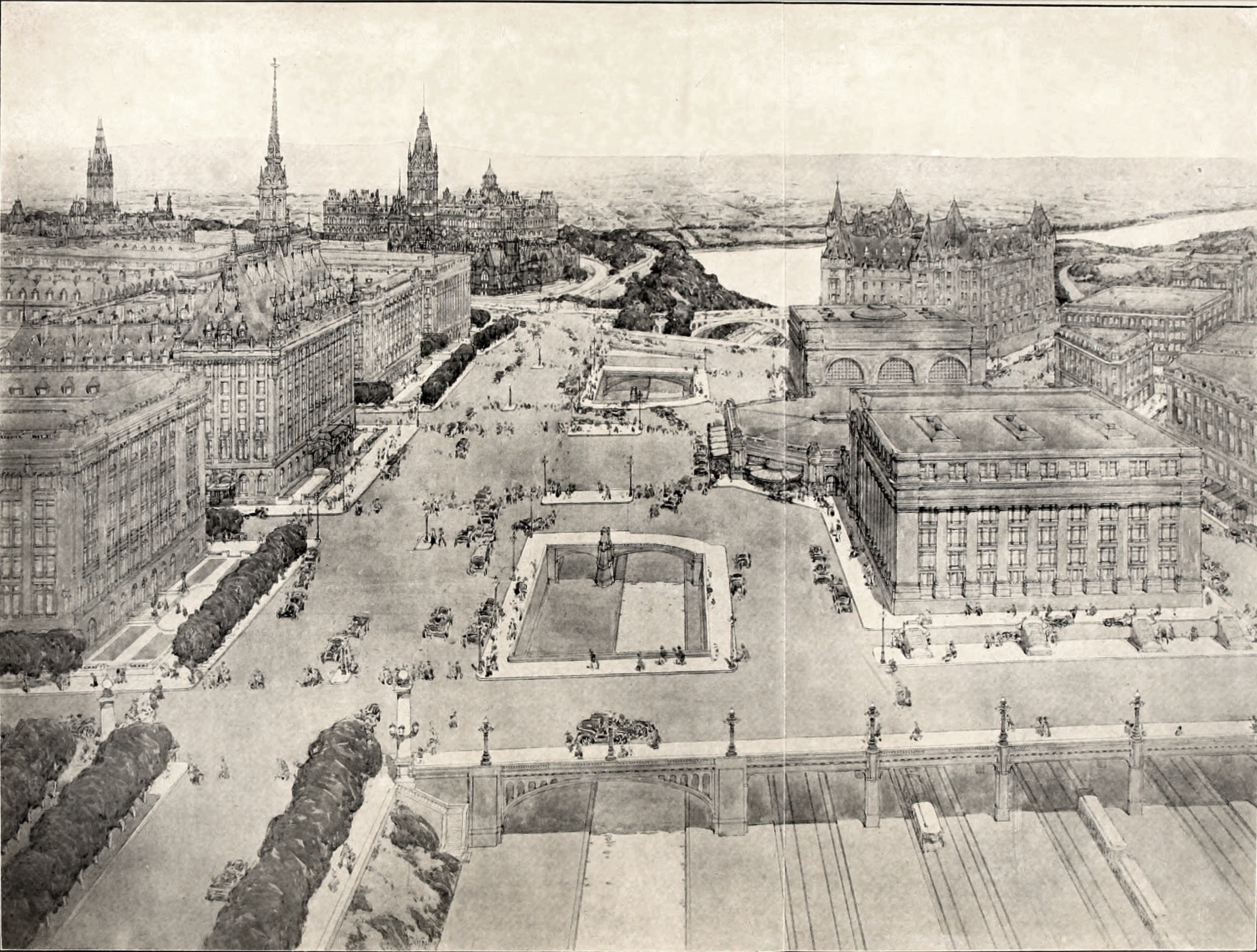

In the early 1900s, Ottawa wrestled with what to do about cramped streets and traffic congestion. A 1915 plan drawn up by urban planner Edward Bennett, never formally adopted, called for a mammoth public square straddling the Rideau Canal and flanked by Beaux-Arts buildings to the west and an expanded Union Station to the east. (Queen’s University)

In the early 1900s, Ottawa wrestled with what to do about cramped streets and traffic congestion. A 1915 plan drawn up by urban planner Edward Bennett, never formally adopted, called for a mammoth public square straddling the Rideau Canal and flanked by Beaux-Arts buildings to the west and an expanded Union Station to the east. (Queen’s University)

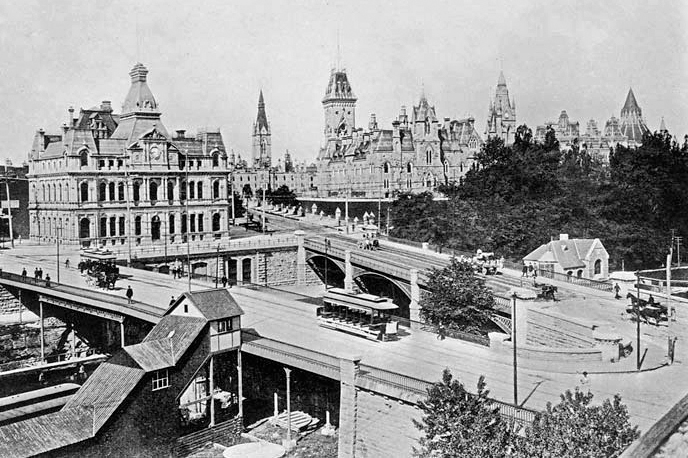

Ottawa’s old post office in 1903, with Parliament Hill in the background. In the foreground are Sapper’s Bridge, built in 1827 and, behind it, Dufferin Bridge, built in the 1870s. Both were torn down and replaced with a single structure, today’s Plaza Bridge, during construction of Union Station. (Library and Archives Canada)

Ottawa’s old post office in 1903, with Parliament Hill in the background. In the foreground are Sapper’s Bridge, built in 1827 and, behind it, Dufferin Bridge, built in the 1870s. Both were torn down and replaced with a single structure, today’s Plaza Bridge, during construction of Union Station. (Library and Archives Canada)

Ottawa’s old post office in 1936, two years before its demolition. In the background is Ottawa’s old City Hall. Union Station is visible on the left. (Library and Archives Canada)

Ottawa’s old post office in 1936, two years before its demolition. In the background is Ottawa’s old City Hall. Union Station is visible on the left. (Library and Archives Canada)

This 1938 composite photo shows construction of the National War Memorial and Confederation Square nearing completion. The old post office has been demolished and its replacement, seen behind the War Memorial, is well underway. (Library and Archives Canada)

This 1938 composite photo shows construction of the National War Memorial and Confederation Square nearing completion. The old post office has been demolished and its replacement, seen behind the War Memorial, is well underway. (Library and Archives Canada)