Let’s Make a Deal: How a reluctant Prince Edward Island joined Canada

For a province nicknamed the “Birthplace of Confederation” it’s ironic that Prince Edward Island balked at joining the newly minted Dominion of Canada in 1867, waiting five years to sign on.

In the end, financial difficulties drove it to make a deal with the goliath next door. On July 1, 1873, Prince Edward Island became Canada’s seventh province. Getting there was a bumpy ride.

In September 1864, representatives of three British colonies — Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick — were gathering in Charlottetown to discuss a proposed Maritime union. Delegates from the Province of Canada — today’s Ontario and Quebec — caught wind of the conference and asked to be included as observers. When the original proposal fizzled, the western delegates seized the moment, pitching a far more ambitious union stretching from the Atlantic to Lake Superior.

P.E.I.’s first four senators included long-time supporters of Confederation as well as skeptics. Thomas Heath Haviland, speaker of the island’s Legislative Assembly, was one of five colonial delegates to the 1864 Charlottetown Conference and an enthusiastic advocate of Confederation.

Robert Poore Haythorne was the colony’s premier from 1869 to 1870 and from 1872 to 1873. Although initially skeptical of Confederation, in 1873 he launched negotiations with Ottawa to secure favourable terms for the island. He served in the Canadian Senate from 1873 until his death in 1891.

George William Howlan, an Irish-born merchant and ship owner was a member of the colony’s Legislative Assembly. He was skeptical of union before 1873. After serving 21 years in the Canadian Senate, he was appointed the province’s sixth Lieutenant Governor.

Donald Montgomery was a farmer and member of P.E.I.’s Legislative Assembly from 1838 to 1874. He served as a Canadian senator from 1873 until 1893. His granddaughter, Lucy Maud Montgomery, was the author of Anne of Green Gables.

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick were persuaded, but Prince Edward Island saw no advantage in joining. Its agriculture and industries were flourishing. Overseas trade was booming. Islanders were content to remain masters of their own affairs rather than junior partners in a union with populous and politically powerful neighbours.

“P.E.I. took a narrow view of its own interests,” Robert Bothwell, emeritus professor of history at the University of Toronto and author of the Penguin History of Canada, said. “But British plans and U.S. politics were leaving it dangerously isolated. Whether it realized it or not, its interests lay in joining the Canadians.”

P.E.I.’s intransigence ended in the 1870s when a trio of long-simmering domestic problems boiled over and forced it to the bargaining table.

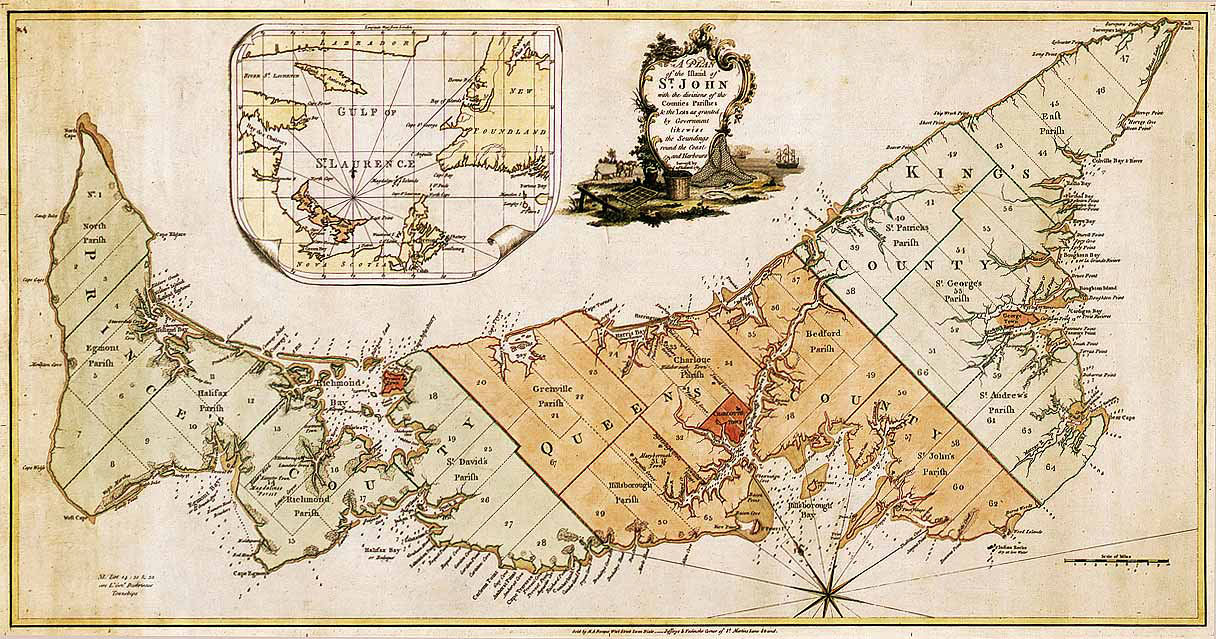

Foremost was the issue of absentee land ownership. France had surrendered the island, which it had named Île Saint-Jean, when the Seven Years’ War ended in 1763. British authorities divided the territory into lots and sold nearly the entirety in a one-time lottery to politically connected landlords, many of whom had never set foot outside Britain.

Few made any effort to settle and develop their overseas properties, as their grants stipulated. Many fell behind in their taxes, starving the colonial administration of one of its few sources of revenue. Resident farmers, who made up the bulk of P.E.I.’s population, remained landless and resentful.

Again and again, the island’s Legislative Assembly petitioned the Colonial Office in London to resolve the issue, but Whitehall failed to hold the landlords to account. By the time of Confederation, the “Land Question” had festered for a century.

Meanwhile, without a reliable year-round link to the mainland, P.E.I.’s economy was beginning to stagnate. Financing a steamship that could operate all winter long in the ice-choked Northumberland Strait — let alone bridging the 13-kilometre-wide channel — was a daunting challenge for the tiny, cash-strapped colony.

To cap it off, Islanders had also caught railway fever. Politicians pressed for a line connecting Elmira on the island’s eastern tip to Tignish at its northwestern extreme, a gargantuan undertaking the island neither needed nor could afford.

“Everybody was building railways then,” Professor Bothwell said. “P.E.I. fell victim to the mania of the day.”

The project began to go off the rails soon after construction began in 1871. Contractors, paid by the mile, maximized profits by meandering long distances around obstacles rather than building tunnels and bridges. Bribery was rampant, needless stations sprouted every few kilometres and costs soared.

Within a year, the island was on the verge of bankruptcy.

The Canadian government reached out, fully aware that the Americans — with designs on carving out a stake in the lucrative Gulf of St. Lawrence fishery — were simultaneously making overtures.

The Canadians agreed to assume the island’s debt and subsidize a buy-out of the remaining absentee landlords. They offered to complete construction of the troubled railway and absorb its debts. Finally, they committed to maintaining a year-round steamship service to the mainland.

Islanders were offered generous political representation — six seats in the elected House of Commons, one more than their population warranted.

What sealed the deal was the constitutional guarantee of an appointed Senate. Senate seats were allocated regionally, not proportionately as in the House of Commons, where each once-a-decade federal census would trigger a recalculation of the island’s seat count. P.E.I.’s four Senate seats was federal representation the island could count on permanently.

“That first cohort of senators held varying opinions on the merits of joining Confederation,” Professor Bothwell said. “But once P.E.I. entered the Canadian political system, its politicians committed to fully becoming part of that system. P.E.I. moved almost seamlessly into the Canadian fold because everyone agreed that was the way forward.

“Canada had become a symbol of modernity and a vivid example of political accommodation.”

Delegates to the Charlottetown Conference in 1864 discussed the possibility of a federal union of Britain’s North American colonies. These talks led to the creation of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867. Although Prince Edward Island’s capital hosted the conference, the colony did not join Confederation until 1873. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Delegates to the Charlottetown Conference in 1864 discussed the possibility of a federal union of Britain’s North American colonies. These talks led to the creation of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867. Although Prince Edward Island’s capital hosted the conference, the colony did not join Confederation until 1873. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

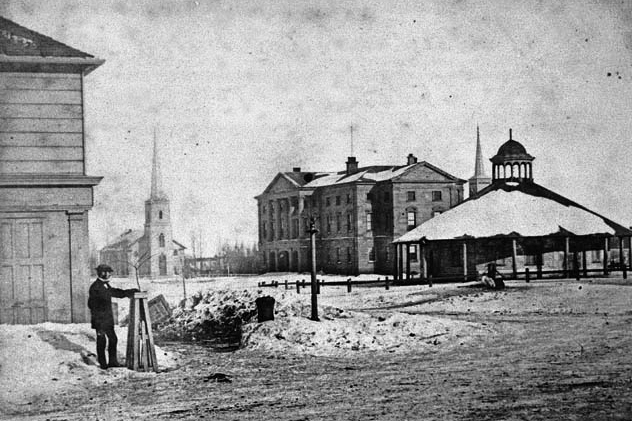

Charlottetown in 1865, one year after it hosted the Charlottetown Conference, with the old farmer’s market on the right and Province House ¬— Prince Edward Island’s legislative building — behind it. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Charlottetown in 1865, one year after it hosted the Charlottetown Conference, with the old farmer’s market on the right and Province House ¬— Prince Edward Island’s legislative building — behind it. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Queen Street, Charlottetown’s main commercial artery in 1867, looking southeast towards the Hillsborough River. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

Queen Street, Charlottetown’s main commercial artery in 1867, looking southeast towards the Hillsborough River. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

A train on the Prince Edward Island Railway pulls into Kensington Station in this early 20th-century photo. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

A train on the Prince Edward Island Railway pulls into Kensington Station in this early 20th-century photo. (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

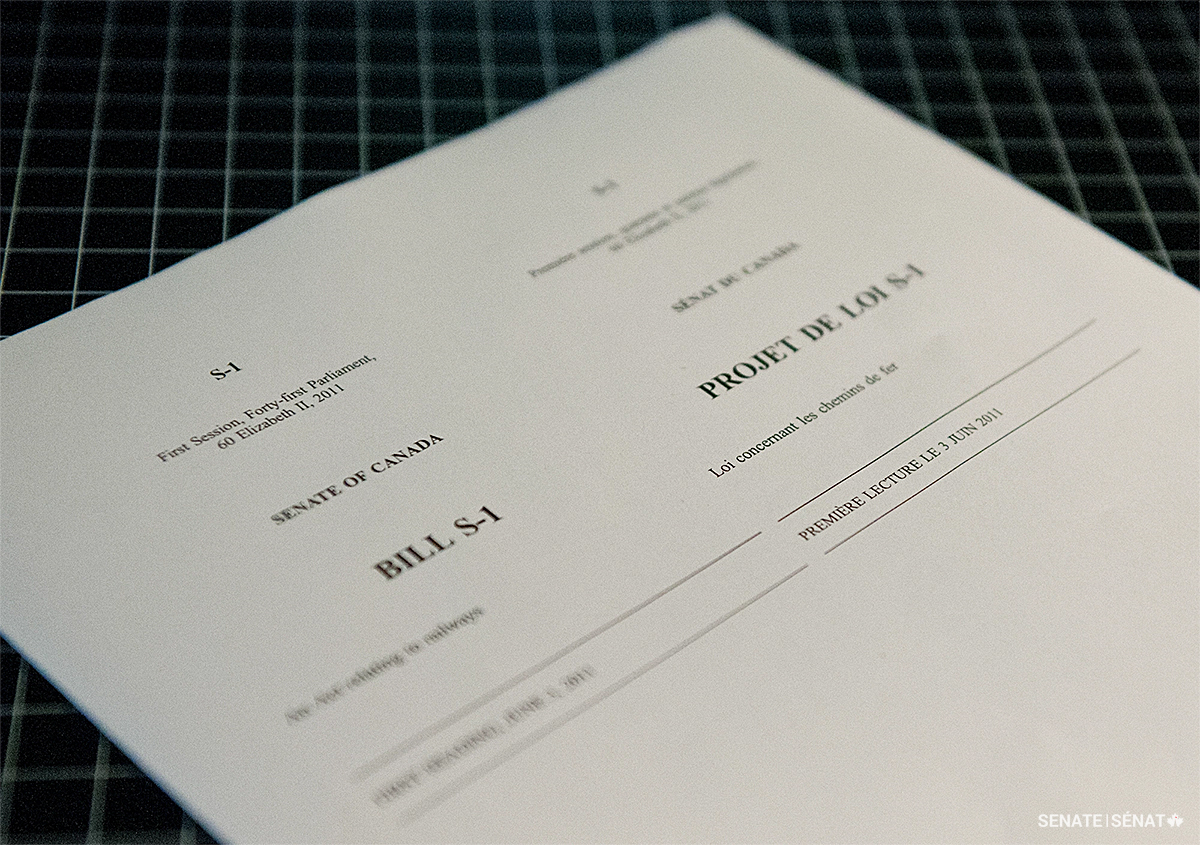

The roles that the Senate and the railway played in bringing the Maritime colonies into Confederation live on in Bill S-1 – An Act relating to railways — legislation introduced at the beginning of each Parliamentary session to demonstrate the Senate’s independence from the Crown.

This 1775 map shows the first survey of Saint John Island — later renamed Prince Edward Island — after the French ceded control to the British. The survey divided the island into 67 lots that were sold off to aristocratic British landlords. This transaction spawned a century of underdevelopment and political deadlock known as “the Land Question.” (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)

This 1775 map shows the first survey of Saint John Island — later renamed Prince Edward Island — after the French ceded control to the British. The survey divided the island into 67 lots that were sold off to aristocratic British landlords. This transaction spawned a century of underdevelopment and political deadlock known as “the Land Question.” (Photo credit: Library and Archives Canada)