The Rose and Crown: Parliament’s royal symbols, part one

In the first of a series of three articles, we explore four of the most frequently seen royal symbols in the Parliamentary Precinct.

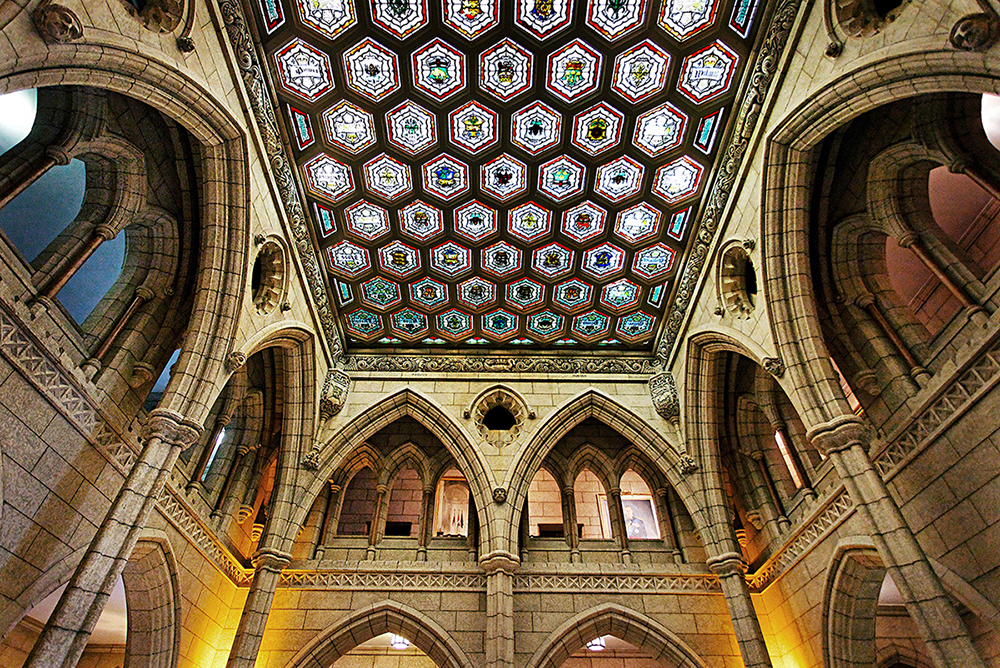

In February 2019, the Senate moved to the Senate of Canada Building, a former train station built in 1912. The Senate will occupy this temporary location while Parliament’s Centre Block — the Senate’s permanent home — is rehabilitated.

Although Centre Block is shuttered for rehabilitation work, Canadians can still experience its art and architecture — as well as the Senate of Canada Building’s — through the Senate’s immersive virtual tours.

Parliament Hill is brimming with ancient symbols of royalty, alluding to Canada’s 800-year-old connection to English parliamentary tradition and to the English, French and Scottish monarchies that predate it.

“All of these symbols reinforce that long relationship between our Parliament and Great Britain’s,” House of Commons curator Johanna Mizgala said. “But Canada’s Parliament is not Westminster. It has very distinct Canadian ideas in place.”

These symbols, although inherited, speak directly to Canadians and to their regional backgrounds.

“They relate to Parliament but also to the places we live,” Ms. Mizgala said. “They serve as reminders of where we come from.”

Here are some you’ll frequently see:

St. Edward’s Crown

Crowns appear throughout Centre Block and the Senate of Canada Building, symbolizing Canada and Britain’s shared tradition of constitutional monarchy.

This version — with its characteristic dipped arches — is both a symbol and a real crown.

Normally on public display in the Tower of London, St. Edward’s Crown was chosen for the coronation ceremonies of King George V, King George VI, Queen Elizabeth II and King Charles III.

The original was made for Edward the Confessor in 1042 but was destroyed during the English Civil War in the 1600s.

The current version was made when King Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660.

It is a familiar symbol to Canadians. During the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, it appeared frequently in coats of arms, badges and other insignia, representing both the monarch personally and the concept of the state and its government as a source of non-partisan sovereign authority.

Tudor Crown

The Tudor Crown is also a symbol and an actual crown.

The distinctive domed shape is associated with the first Tudor king, Henry VII, who reigned from 1485 to 1509.

A century and a half later, King Charles I commissioned the definitive version, with four pearl-studded arches rising almost to a point. This crown was destroyed during the short-lived Commonwealth that followed the king’s execution in 1649.

It was resurrected by Queen Victoria in 1880. As Empress of India, she chose to be represented by a high-arched imperial crown.

Her successors adopted it as their royal insignia and it was reproduced widely in Canada on coins, postage stamps, passports and official documents.

Centre Block was no exception. When it was rebuilt after the 1916 fire, the Tudor Crown featured prominently in the building’s sculptural program.

Tudor rose

“The Tudor rose is part of the origin story of Parliament itself,” Ms. Mizgala said. “It connects our parliamentary system all the way back to Tudor England.”

In 1485, Henry Tudor crushed his rival, King Richard III, at the Battle of Bosworth Field. The victory of the House of Lancaster over the rival House of York ended the bloody 30-year War of the Roses and finally settled the question of succession.

The astute King Henry VII immediately adopted the Tudor rose as his emblem, merging the Lancastrian red and Yorkist white roses into a symbol of national reconciliation.

The Tudors instituted reforms that paved the way for Britain and Canada’s modern parliamentary systems. The House of Commons moved into the Palace of Westminster, more systematic records of debates were kept, and the notion of Parliamentary privilege emerged. In this way, the Tudor rose gradually evolved from a dynastic symbol into a symbol of Parliament itself.

Tudor roses appear throughout Centre Block, notably in the Speaker’s dais in the Senate Chamber.

Portcullis

The portcullis, a fortified, retractable castle gate, is one of Centre Block’s more arcane symbols.

“The portcullis, in a parliamentary context, is a symbol of authority and the duty to protect a community,” Ms. Mizgala explained.

It evolved from a badge of England’s ruling Tudor dynasty to an emblem of Parliament itself. King Henry VII inherited the portcullis and the Tudor rose as family emblems and used them to represent the dynasty he founded.

It was under the Tudors that London’s Palace of Westminster became the venue where Parliament met regularly.

When fire destroyed the palace in 1834, the architect Charles Barry was commissioned to design its replacement.

He made wide use of the portcullis symbol throughout the building to represent the concept that the palace, once the stronghold of kings, had risen from the ashes to become a bastion of the people.

“In the 1860s, Canada’s first Parliament Building drew inspiration from the recently rebuilt Westminster Palace,” Ms. Mizgala said. “Many of its concepts and symbols, like the portcullis, made their way into our building.”