The Chinese Exclusion Act’s dark centennial holds lessons for today: Senator Simons

Tags

On July 1, millions of Canadians celebrated the promise of a country that prides itself on its multicultural inclusion. But for Chinese Canadians, especially those in Western Canada, this past Canada Day was bittersweet. July 1, 2023 marked the 100th anniversary of Humiliation Day: when the racist government of William Lyon Mackenzie King brought into force its infamous Chinese Exclusion Act.

The act effectively slammed the door on Chinese immigration to Canada. By some calculations, fewer than 50 people (and according to some sources, as few as 15) were allowed to emigrate from China to Canada between 1923 and 1947, when the act was finally lifted.

In 1921, Canada admitted 2,707 immigrants from China. In 1924, we admitted three. By 1925? Only one.

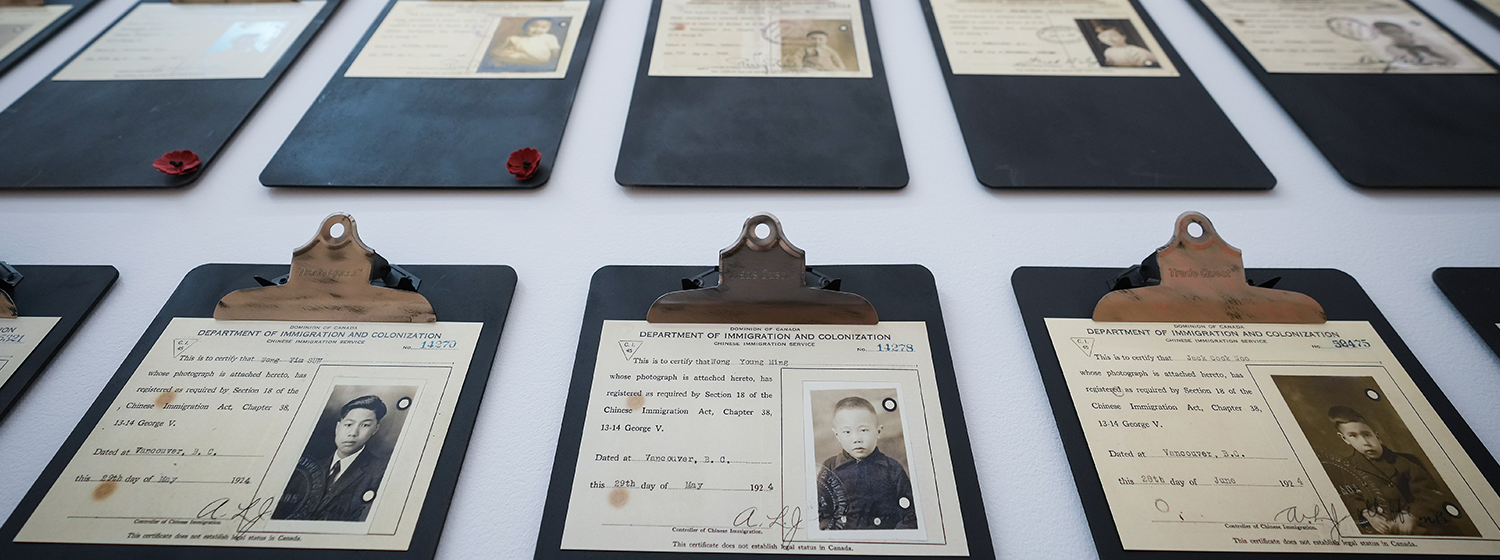

Chinese Canadians who were already in this country — including those who’d been born and raised here — all had to register and carry photo identification, under threat of deportation.

Because of the difficulty of travel, made all the more expensive by the heavy “head tax” which the federal government had levied on Chinese immigrants, it had been common practice for Chinese men to come to Western Canada to establish themselves, hoping to bring their wives and children to Canada later. Now, that opportunity evaporated.

Many families were permanently separated, family ties forever sundered. Others were cut off from spouses and kids for decades and decades.

By 1931, the ratio of Chinese men to women in Toronto was 15 to one. In Calgary, there were 12 Chinese men for every one woman. In Vancouver, there were 11 times as many Chinese men as women.

Eventually, the law’s natural consequences became evident. The Chinese population of Canada started to fall.

In 1931, there were 11,592 Chinese people living in Vancouver. By 1941, there were only 5,973.

Between 1921 and 1951, Canada’s overall Chinese population dropped by 25%. In other words, the Exclusion Act didn’t just keep Chinese immigrants from coming in. Its racism drove many of those who were already here back out again.

It was not only Chinese Canadians — and would-be Chinese Canadians — who suffered as a result of the Exclusion Act. Canada, too, paid for its bigotry — by losing out on the talent and drive of those who were denied entry. Arguably, British Columbia and Alberta paid the biggest economic and social price for their intolerance since they had drawn some of the largest Chinese immigrant communities.

As we mark this dark centennial, it would be nice to say that we have put the bad, old days behind us and come to understand the tragic cost of xenophobia.

Instead, Canada’s Chinese Canadian community is facing new, but sadly familiar, challenges as fears about the impact and influence of Xi Jinping’s regime have some people questioning the loyalty and “Canadian-ness” of those with Chinese roots.

Well-founded allegations of interference by the Chinese government into provincial or federal Canadian politics should be properly, thoroughly and swiftly investigated. We should take the issue of our national security seriously and not use it as a cheap way to score partisan political points.

But let us be extraordinarily careful not to make lazy, dangerous assumptions about the loyalties of tens of thousands of Chinese Canadians.

Asian Canadians have already suffered through ugly racism, prompted by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, Chinese Canadians — including politicians and community leaders — find themselves smeared and scapegoated in the face of allegations about the interference in Canadian affairs by the government in Beijing.

We cannot and should not allow foreign government or foreign actors to influence our elections — whether that influence comes from Russia or China or the United States or India or elsewhere. But in our haste to protect our democracy, we must not sacrifice core democratic values. Some of the heated rhetoric around this issue — even when it’s well-intended — could have the result, not just of defaming specific Chinese Canadians in public life, but also of fuelling a corrosive suspicion of Chinese Canadians more broadly.

Indeed, there is nothing our enemies would like more than to sow suspicion and discord amongst us, to see us turn on one another, to foster disunity when we most need to be united.

Let’s be sure we learn the lessons of history. And let’s be sure we celebrate the extraordinary legacy of Chinese Canadians who have given so much to the country we all love.

Senator Paula Simons represents Alberta.

This article was published in the Edmonton Journal on June 30, 2023.

On July 1, millions of Canadians celebrated the promise of a country that prides itself on its multicultural inclusion. But for Chinese Canadians, especially those in Western Canada, this past Canada Day was bittersweet. July 1, 2023 marked the 100th anniversary of Humiliation Day: when the racist government of William Lyon Mackenzie King brought into force its infamous Chinese Exclusion Act.

The act effectively slammed the door on Chinese immigration to Canada. By some calculations, fewer than 50 people (and according to some sources, as few as 15) were allowed to emigrate from China to Canada between 1923 and 1947, when the act was finally lifted.

In 1921, Canada admitted 2,707 immigrants from China. In 1924, we admitted three. By 1925? Only one.

Chinese Canadians who were already in this country — including those who’d been born and raised here — all had to register and carry photo identification, under threat of deportation.

Because of the difficulty of travel, made all the more expensive by the heavy “head tax” which the federal government had levied on Chinese immigrants, it had been common practice for Chinese men to come to Western Canada to establish themselves, hoping to bring their wives and children to Canada later. Now, that opportunity evaporated.

Many families were permanently separated, family ties forever sundered. Others were cut off from spouses and kids for decades and decades.

By 1931, the ratio of Chinese men to women in Toronto was 15 to one. In Calgary, there were 12 Chinese men for every one woman. In Vancouver, there were 11 times as many Chinese men as women.

Eventually, the law’s natural consequences became evident. The Chinese population of Canada started to fall.

In 1931, there were 11,592 Chinese people living in Vancouver. By 1941, there were only 5,973.

Between 1921 and 1951, Canada’s overall Chinese population dropped by 25%. In other words, the Exclusion Act didn’t just keep Chinese immigrants from coming in. Its racism drove many of those who were already here back out again.

It was not only Chinese Canadians — and would-be Chinese Canadians — who suffered as a result of the Exclusion Act. Canada, too, paid for its bigotry — by losing out on the talent and drive of those who were denied entry. Arguably, British Columbia and Alberta paid the biggest economic and social price for their intolerance since they had drawn some of the largest Chinese immigrant communities.

As we mark this dark centennial, it would be nice to say that we have put the bad, old days behind us and come to understand the tragic cost of xenophobia.

Instead, Canada’s Chinese Canadian community is facing new, but sadly familiar, challenges as fears about the impact and influence of Xi Jinping’s regime have some people questioning the loyalty and “Canadian-ness” of those with Chinese roots.

Well-founded allegations of interference by the Chinese government into provincial or federal Canadian politics should be properly, thoroughly and swiftly investigated. We should take the issue of our national security seriously and not use it as a cheap way to score partisan political points.

But let us be extraordinarily careful not to make lazy, dangerous assumptions about the loyalties of tens of thousands of Chinese Canadians.

Asian Canadians have already suffered through ugly racism, prompted by the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, Chinese Canadians — including politicians and community leaders — find themselves smeared and scapegoated in the face of allegations about the interference in Canadian affairs by the government in Beijing.

We cannot and should not allow foreign government or foreign actors to influence our elections — whether that influence comes from Russia or China or the United States or India or elsewhere. But in our haste to protect our democracy, we must not sacrifice core democratic values. Some of the heated rhetoric around this issue — even when it’s well-intended — could have the result, not just of defaming specific Chinese Canadians in public life, but also of fuelling a corrosive suspicion of Chinese Canadians more broadly.

Indeed, there is nothing our enemies would like more than to sow suspicion and discord amongst us, to see us turn on one another, to foster disunity when we most need to be united.

Let’s be sure we learn the lessons of history. And let’s be sure we celebrate the extraordinary legacy of Chinese Canadians who have given so much to the country we all love.

Senator Paula Simons represents Alberta.

This article was published in the Edmonton Journal on June 30, 2023.