Senator Lillian Eva Dyck celebrates Science Literacy Week

Science Literary Week, held from September 17 to 23, is a weeklong celebration of science and space in Canada. To mark this celebration, SenCAplus sat down with Senator Lillian Eva Dyck to discuss her background as a neurochemist, and to reflect on how that work prepared her for the Senate.

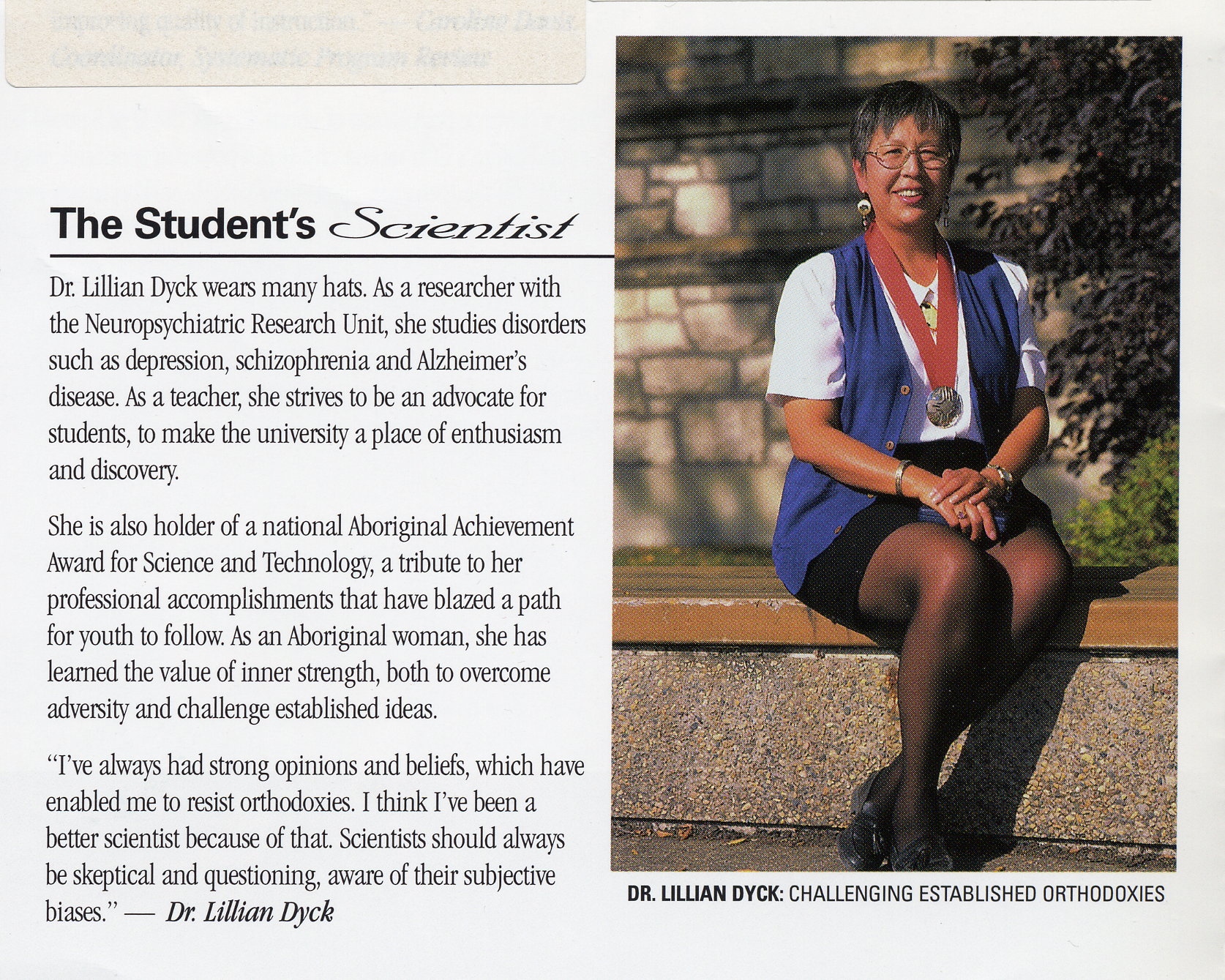

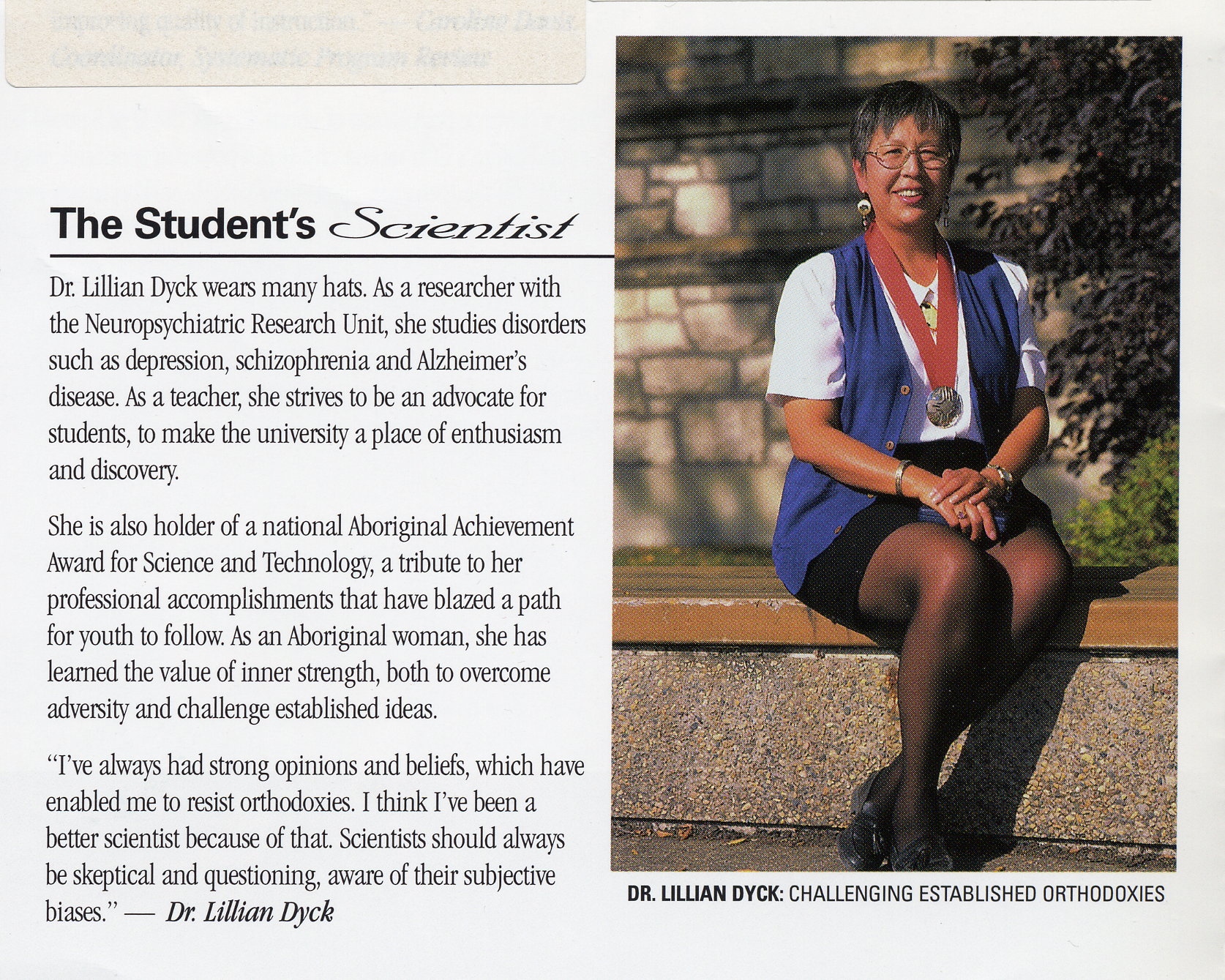

Senator Dyck has a PhD in biological psychiatry from the University of Saskatchewan and she is known for advocating for equity in the education and employment of women, Chinese Canadians and Indigenous peoples. She is the first female First Nations senator and first Canadian-born Chinese senator.

How did you first become interested in science?

What got me into science was my brother and my high school science teacher. What kept me in science was being able to get jobs in the summer as an undergraduate student working in the chemistry and biochemistry lab. I loved it. I didn’t really need inspiration from a role model. There really weren’t any for me. I loved doing the lab work, conducting experiments and figuring out what the results meant. It was a lot of fun, I really enjoyed it.

I’ve always been fascinated with how things work, especially biologically. My main interest as I got older was in the chemistry of the brain and how recreational drug use affects brain functioning.

I grew up in the hippie era, when there were a lot of people taking psychedelic drugs and tripping out. It was the 1960s and ‘70s, when a lot of people were doing LSD deliberately and that kind of made me wonder what it was doing to their brains. And of course a secondary interest, too, was alcohol: the most commonly abused drug.

How did being a scientist prepare you for your work in the Senate?

When you’ve been a scientist, you develop a way of thinking involving strong logical analytical skills. You’re very interested in analyzing things, looking at the evidence as objectively as possible, determining the strength of the evidence. In the senate, I continued to use my scientific analytical skills to solve the problems that come before me in terms of policy issues and bills.

You still use the same style of thinking. You’re not so easily swayed by arguments that don’t have a lot of evidence behind them. You really want to see strong evidence and facts, whereas some people are swayed more by emotion than by fact and reason. I think most people would agree that evidence-based policy is what we’re striving for. That means you have a policy that’s sound, that’s based on fact and not on someone’s opinion or some smidgen of information, which may not be reliable or may not give you the whole story.

How do you encourage Canadians to be more science literate?

I’ve visited and made speeches to all levels of school kids to encourage them to take science. Being a woman in science, especially for someone my age, is unusual. I’ve always worked in labs where I was the only female scientist. Although there were barriers for me as an Indigenous woman in science, I still thought it was a good career choice, which others like me could enjoy and make their own unique contribution.

A lot of people are afraid of science, they think it’s hard, they avoid math, they avoid the sciences, and I think that’s kind of a shame. I also wanted to encourage more women and more Indigenous people to enter into science. So, a lot of my so-called spare time was spent speaking to high school students and elementary school kids to promote an interest in science.

The feminist movement, the women’s movement, certainly increased the number of women who study science.

When I started graduate studies in the early ‘60s, for example, it was very uncommon for there to be women in chemistry class. Now, the majority of undergraduate students in science are female, except for engineering, mathematics, physics and computer science. But in biology, women are the majority. In veterinary medicine, women have almost taken over. Having programs for science promotion — especially at the elementary level and all the way up through every level of school — for women made a huge difference.

Now, for Indigenous students, there are a few science promotion programs such as the Science Ambassador program at my university (the University of Saskatchewan) and science fairs put on by the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations.

I’m really hopeful because I’ve seen how those programs, science camps, science fairs and so on, have made a huge difference in getting more women into science and I’m sure they’ll make a big difference and get more Indigenous people into science careers, too.

Note to readers: The Honourable Lillian Dyck retired from the Senate of Canada in August 2020. Learn more about her work in Parliament.

Related articles

Tags

Committee news

Senator Lillian Eva Dyck celebrates Science Literacy Week

Science Literary Week, held from September 17 to 23, is a weeklong celebration of science and space in Canada. To mark this celebration, SenCAplus sat down with Senator Lillian Eva Dyck to discuss her background as a neurochemist, and to reflect on how that work prepared her for the Senate.

Senator Dyck has a PhD in biological psychiatry from the University of Saskatchewan and she is known for advocating for equity in the education and employment of women, Chinese Canadians and Indigenous peoples. She is the first female First Nations senator and first Canadian-born Chinese senator.

How did you first become interested in science?

What got me into science was my brother and my high school science teacher. What kept me in science was being able to get jobs in the summer as an undergraduate student working in the chemistry and biochemistry lab. I loved it. I didn’t really need inspiration from a role model. There really weren’t any for me. I loved doing the lab work, conducting experiments and figuring out what the results meant. It was a lot of fun, I really enjoyed it.

I’ve always been fascinated with how things work, especially biologically. My main interest as I got older was in the chemistry of the brain and how recreational drug use affects brain functioning.

I grew up in the hippie era, when there were a lot of people taking psychedelic drugs and tripping out. It was the 1960s and ‘70s, when a lot of people were doing LSD deliberately and that kind of made me wonder what it was doing to their brains. And of course a secondary interest, too, was alcohol: the most commonly abused drug.

How did being a scientist prepare you for your work in the Senate?

When you’ve been a scientist, you develop a way of thinking involving strong logical analytical skills. You’re very interested in analyzing things, looking at the evidence as objectively as possible, determining the strength of the evidence. In the senate, I continued to use my scientific analytical skills to solve the problems that come before me in terms of policy issues and bills.

You still use the same style of thinking. You’re not so easily swayed by arguments that don’t have a lot of evidence behind them. You really want to see strong evidence and facts, whereas some people are swayed more by emotion than by fact and reason. I think most people would agree that evidence-based policy is what we’re striving for. That means you have a policy that’s sound, that’s based on fact and not on someone’s opinion or some smidgen of information, which may not be reliable or may not give you the whole story.

How do you encourage Canadians to be more science literate?

I’ve visited and made speeches to all levels of school kids to encourage them to take science. Being a woman in science, especially for someone my age, is unusual. I’ve always worked in labs where I was the only female scientist. Although there were barriers for me as an Indigenous woman in science, I still thought it was a good career choice, which others like me could enjoy and make their own unique contribution.

A lot of people are afraid of science, they think it’s hard, they avoid math, they avoid the sciences, and I think that’s kind of a shame. I also wanted to encourage more women and more Indigenous people to enter into science. So, a lot of my so-called spare time was spent speaking to high school students and elementary school kids to promote an interest in science.

The feminist movement, the women’s movement, certainly increased the number of women who study science.

When I started graduate studies in the early ‘60s, for example, it was very uncommon for there to be women in chemistry class. Now, the majority of undergraduate students in science are female, except for engineering, mathematics, physics and computer science. But in biology, women are the majority. In veterinary medicine, women have almost taken over. Having programs for science promotion — especially at the elementary level and all the way up through every level of school — for women made a huge difference.

Now, for Indigenous students, there are a few science promotion programs such as the Science Ambassador program at my university (the University of Saskatchewan) and science fairs put on by the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations.

I’m really hopeful because I’ve seen how those programs, science camps, science fairs and so on, have made a huge difference in getting more women into science and I’m sure they’ll make a big difference and get more Indigenous people into science careers, too.

Note to readers: The Honourable Lillian Dyck retired from the Senate of Canada in August 2020. Learn more about her work in Parliament.