Senators reflect on the Battle of Vimy Ridge 100 years later

In the Douai plain of northeastern France, a seven-kilometre ridge rises from the rolling landscape of farms, canals, wood lots and industrial towns. At its highest point, two stone pillars rise from the ground — a towering memorial to the fallen.

Today, Vimy Ridge is a museum — a monument to hope and victory. But in April 1917, this corner of the world was a cemetery.

The First World War and the Battle of Vimy Ridge are significant to Canada’s Senate. During the war, senators visited the front lines by the River Somme to show their support for the troops.

Later, a Ministry of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment was created to help veterans re-integrate into Canadian society. Its minister was a senator, James Alexander Lougheed.

The Senate’s most visible link is the War Paintings that hang on the walls of the Red Chamber to remind senators of the sacrifices Canadians made between 1914 and 1918.

The Senate Subcommittee on Veterans Affairs is one of Parliament’s strongest advocates for Canada’s soldiers and veterans. The committee’s work includes studies on post-traumatic stress disorder and advocacy for better presentation of soldiers’ perspectives in the Canadian War Museum.

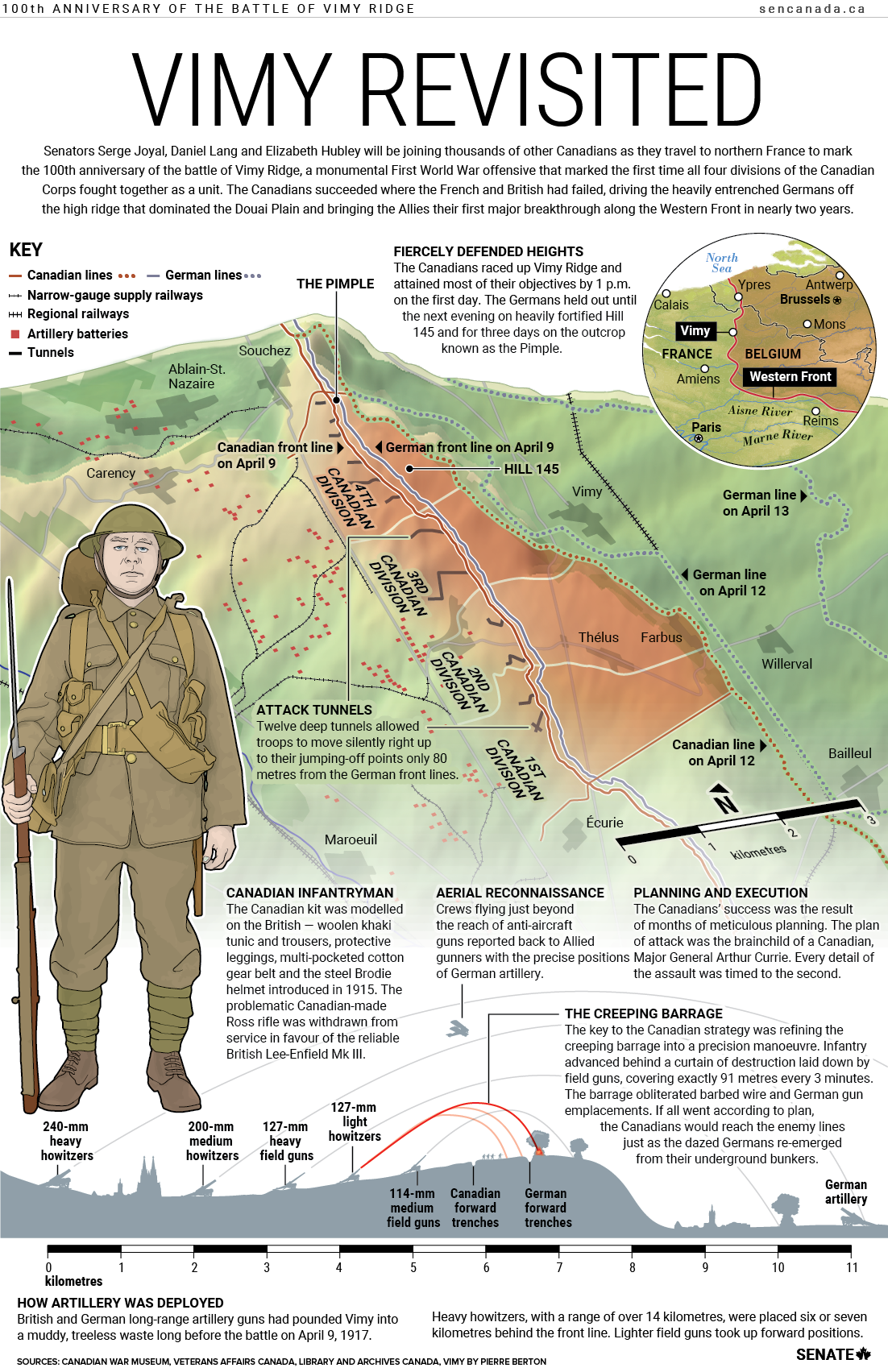

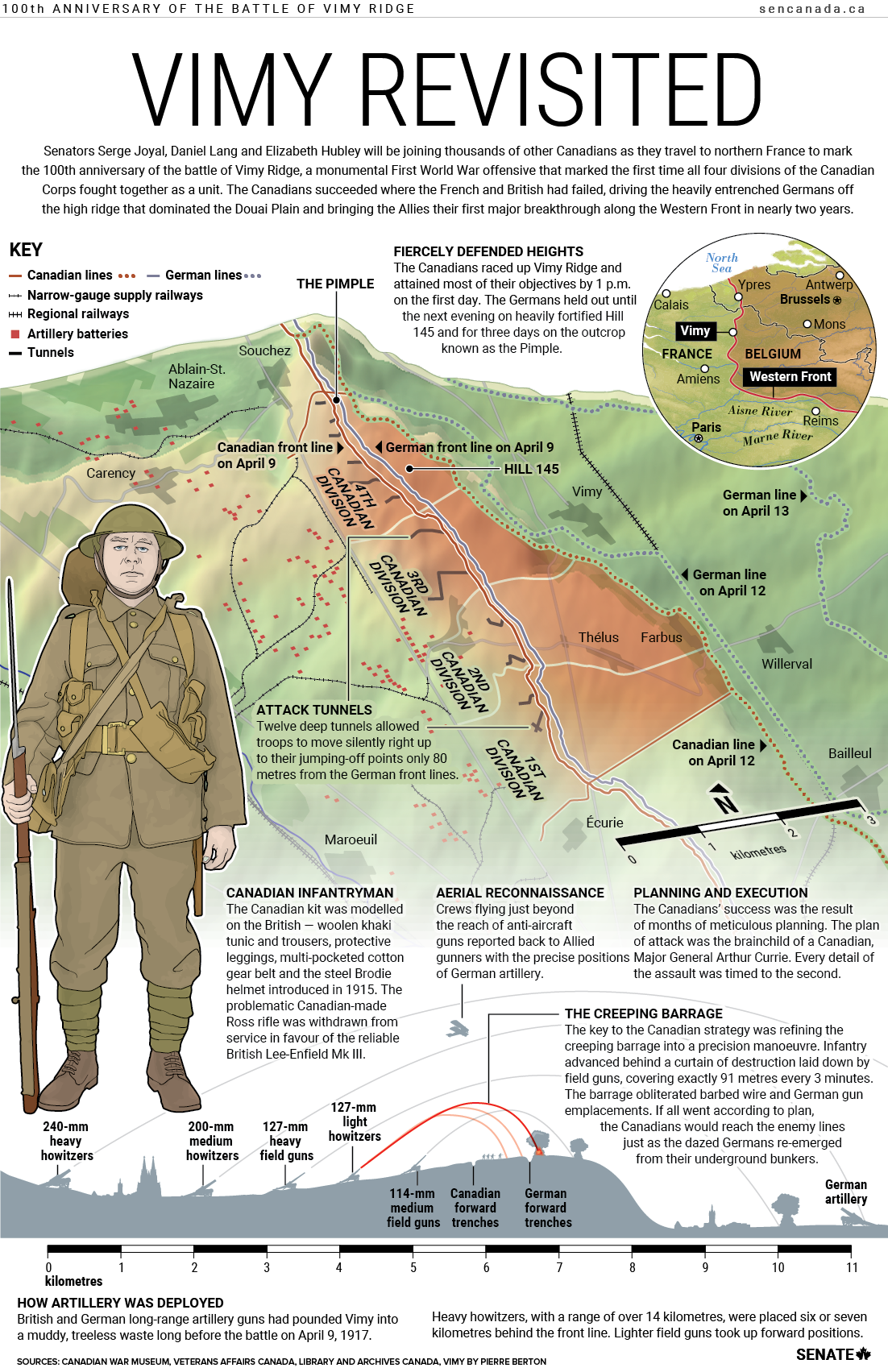

The Battle of Vimy Ridge began on April 9, 1917, but has taken on legendary status for Canadians in the past century.

The ridge is a massive outcrop of chalk — easy to tunnel and reinforce, which is exactly what German soldiers had been doing since 1915. The Canadians faced a fortress of limestone, honeycombed with tunnels, scarred by trenches, sheathed in barbed wire and riddled with gun posts. The French and British had repeatedly failed to take the ridge.

Lt.-Gen. Sir Julian Byng commanded a British and Canadian force of 170,000 soldiers on the Western Front, including 97,000 in the four Canadian army divisions. But the personality most associated with the battle’s success was 1st Canadian Division commander Arthur Currie, a real estate broker from Victoria who found his calling on the battlefield. His meticulous planning set him apart from many of his British counterparts. His ability to learn from mistakes helped him rise through the ranks.

What unfolded was a remarkable display of Canadian ingenuity, drive and discipline. Since the war began in 1914, no battle had been planned with such precision.

The Canadians prepared by digging a series of 12 tunnels to allow troops to move up to their jumping-off points only 80 metres from the German front lines. It was a virtual underground city, with electricity and piped-in water.

For a week before the assault, 1,000 Canadian and British artillery guns pounded the German position, raining more than a million shells down on the entrenched Germans.

At 5:30 a.m. on April 9, a miserable Easter Monday, 20,000 Allied soldiers who formed the first attack wave stood shivering in the trenches in the grey light of dawn.

Then the Battle of Vimy Ridge began.

Troops inched forward behind a creeping barrage of artillery fire. Timing was everything. Byng told his troops: “Chaps, you shall go over exactly like a railroad train, on time, or you shall be annihilated.”

The two highest points on the ridge held out the longest. German troops returned fire for 24 hours before they were driven off the heavily fortified Hill 145. They held out even longer atop the ridge’s northernmost knoll, called “the Pimple”, fending off successive, determined Canadian assaults until they were forced to retreat on April 12.

The Germans withdrew three kilometres east across the Douai plain. Canadian troops who survived the attack stood on the ridge and looked out over a surreal scene. They saw fleeing German troops and the German war machine — its camps, guns and rail lines — humming away like a model railroad. Behind the Canadians lay a grey wasteland of craters, tree stumps and an endless sea of mud. In front of them lay an Eden of green fields and thick forests.

Almost 3,600 Canadians died at Vimy. Another 7,000 were wounded. But out of the muck and mire of Vimy, a new Canada emerged.

Now, 100 years later, Canadians look back with pride and awe at the sacrifices made by their soldiers — immortalized by these two pillars on a hill.

Related articles

Tags

Committee news

Senators reflect on the Battle of Vimy Ridge 100 years later

In the Douai plain of northeastern France, a seven-kilometre ridge rises from the rolling landscape of farms, canals, wood lots and industrial towns. At its highest point, two stone pillars rise from the ground — a towering memorial to the fallen.

Today, Vimy Ridge is a museum — a monument to hope and victory. But in April 1917, this corner of the world was a cemetery.

The First World War and the Battle of Vimy Ridge are significant to Canada’s Senate. During the war, senators visited the front lines by the River Somme to show their support for the troops.

Later, a Ministry of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment was created to help veterans re-integrate into Canadian society. Its minister was a senator, James Alexander Lougheed.

The Senate’s most visible link is the War Paintings that hang on the walls of the Red Chamber to remind senators of the sacrifices Canadians made between 1914 and 1918.

The Senate Subcommittee on Veterans Affairs is one of Parliament’s strongest advocates for Canada’s soldiers and veterans. The committee’s work includes studies on post-traumatic stress disorder and advocacy for better presentation of soldiers’ perspectives in the Canadian War Museum.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge began on April 9, 1917, but has taken on legendary status for Canadians in the past century.

The ridge is a massive outcrop of chalk — easy to tunnel and reinforce, which is exactly what German soldiers had been doing since 1915. The Canadians faced a fortress of limestone, honeycombed with tunnels, scarred by trenches, sheathed in barbed wire and riddled with gun posts. The French and British had repeatedly failed to take the ridge.

Lt.-Gen. Sir Julian Byng commanded a British and Canadian force of 170,000 soldiers on the Western Front, including 97,000 in the four Canadian army divisions. But the personality most associated with the battle’s success was 1st Canadian Division commander Arthur Currie, a real estate broker from Victoria who found his calling on the battlefield. His meticulous planning set him apart from many of his British counterparts. His ability to learn from mistakes helped him rise through the ranks.

What unfolded was a remarkable display of Canadian ingenuity, drive and discipline. Since the war began in 1914, no battle had been planned with such precision.

The Canadians prepared by digging a series of 12 tunnels to allow troops to move up to their jumping-off points only 80 metres from the German front lines. It was a virtual underground city, with electricity and piped-in water.

For a week before the assault, 1,000 Canadian and British artillery guns pounded the German position, raining more than a million shells down on the entrenched Germans.

At 5:30 a.m. on April 9, a miserable Easter Monday, 20,000 Allied soldiers who formed the first attack wave stood shivering in the trenches in the grey light of dawn.

Then the Battle of Vimy Ridge began.

Troops inched forward behind a creeping barrage of artillery fire. Timing was everything. Byng told his troops: “Chaps, you shall go over exactly like a railroad train, on time, or you shall be annihilated.”

The two highest points on the ridge held out the longest. German troops returned fire for 24 hours before they were driven off the heavily fortified Hill 145. They held out even longer atop the ridge’s northernmost knoll, called “the Pimple”, fending off successive, determined Canadian assaults until they were forced to retreat on April 12.

The Germans withdrew three kilometres east across the Douai plain. Canadian troops who survived the attack stood on the ridge and looked out over a surreal scene. They saw fleeing German troops and the German war machine — its camps, guns and rail lines — humming away like a model railroad. Behind the Canadians lay a grey wasteland of craters, tree stumps and an endless sea of mud. In front of them lay an Eden of green fields and thick forests.

Almost 3,600 Canadians died at Vimy. Another 7,000 were wounded. But out of the muck and mire of Vimy, a new Canada emerged.

Now, 100 years later, Canadians look back with pride and awe at the sacrifices made by their soldiers — immortalized by these two pillars on a hill.